Get lost in landscapes from Seattle to Colton, Oregon.

Rogue Routes: The Road to Camp Colton

Lush rainforests filled with ethereal shades of green; foggy beaches that stretch on for miles; towering mountains that dominate city skylines. It’s hard to think of a region with more diverse natural beauty than the Pacific Northwest. Take a journey from Seattle to Colton through the environments that have inspired artists, musicians, and storytellers for generations. From ancient mountains to reclaimed lands, these places are filled with excitement, intrigue, and maybe even a little off-road mystery.

1. Gas Works Park

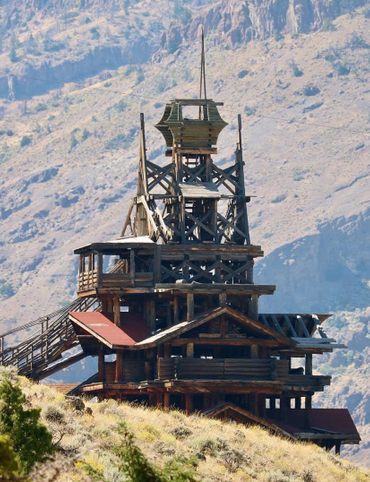

On the shores of Seattle’s Lake Union, joggers, bikers, and kite-flyers move through a green space against a backdrop of rusty red towers. These structures, now long out of commission, were once the Seattle Gas Light Company's gasification plant, which operated from 1906 to 1956. Today they make up the backbone of Gas Works Park, a pioneering feat of landscape architecture.

Out of the 15,000 gas plants built across America, the gasification equipment at Gas Works Park are the last of their kind. The tallest cylinders stand nearly 100 feet tall, while others are short and squat. Interconnected pipes run through the structure, and ivy trails along its sides.

In 1962, the 20-acre site was acquired by the City of Seattle. Half a century of industry had left its mark on the site, but landscape architect Richard Haag saw potential beyond the pollution. Instead of carting off the iron structures, he designed a park that incorporated the towers into public space. Their presence helped ensure that the city’s industrial history would be remembered. After several years of work and soil remediation, Gas Works Park opened in 1975. It was the first project of its kind, a bold idea that has inspired others to reclaim industrial sites and transform them into community spaces.

Before you hit the road, stop by Gas Works Park to take in a view of Lake Union and see the towering structures of the former plant up close (just stay behind the fence).

2101 N Northlake Way, Seattle, WA 98103

2. Beacon Food Forest

Forage your own path at this public park, where visitors are invited to harvest their own produce. The Beacon Food Forest is the first public, edible permaculture garden of its size.

In 2009, four students living in Seattle’s Beacon Hill neighborhood came up with an idea for a plot of grass west of Jefferson Park. They were studying permaculture design, and saw an opportunity to turn the plot of land into a self-sustaining ecosystem capable of providing fresh, local food to the community. Working with the city, they designed a seven-acre community garden that is now the Beacon Food Forest.

The garden mimics a forest ecosystem with plants carefully arranged to help each other grow. The first trees were planted in 2012. Since then, volunteers have transformed the park into an edible landscape that includes the food forest, a learning space, a “giving garden” for donating produce, and a number of private garden plots. Carla Penderock, community outreach coordinator for the forest, described it to Curbed as “a place for people who want a breath of fresh air, who want nature in the city.”

Today there are more than 100 edible, medicinal, and crafting plants cultivated at the forest. All are welcome to stop by and harvest whatever is currently in season. Signs throughout the garden will direct you to the food forest, vegetable garden, and herb garden.

S Dakota St, Seattle, WA 98108

3. Mount St. Helens Visitor Center

On May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens erupted in a high-speed blast that leveled millions of trees and ripped soil from bedrock. It was the largest volcanic eruption in the United States in recorded history. The Mount St. Helens Visitor Center at Silver Lake opened its doors to the public just a few years later. The center functions as a gateway to the mountain, which is located 30 miles to the east. Outside, a mile-long trail meanders into marshy plains surrounding Silver Lake, where you can see waterfowl and a distant view of the stratovolcano.

Silver Lake was not massively changed in 1980, but an earlier eruption of Mount St. Helens is the reason that it exists at all. The wide, shallow lake formed about 2,500 years ago during an era that geologists call the Pine Creek eruptive period. Then, as in 1980, the eruption of Mount St. Helens triggered the same kind of destructive volcanic mudslides, which geologists call lahars. When the mass of rocky debris finally came to a rest it had blocked off Outlet Creek, which slowly pooled into the large body of water we now call Silver Lake.

While the center itself is closed at the moment (it will open back up sometime in 2021), its outdoor trail is still accessible, along with restrooms and a small gift shop. Park at the visitor center and stretch your legs while taking in a view of the western slope of Mount St. Helens, rising above a lake of its own creation.

3029 Spirit Lake Hwy, Castle Rock, WA 98611

4. Untitled (Johnson Pit #30)

Robert Morris was an artistic trail blazer who helped shape some of the prevailing movements of the 1960s and 70s. His sculptures and sketches can be found in art collections around the world, but one of his boldest pieces can’t be contained by any museum. It’s a large-scale public installation near the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

In 1979, the King County Arts Commission (now known as 4culture), brought artists and government agencies together to create artwork out of former industrial land. Morris’s Earthwork sculpture was the first piece completed for the project. He took Johnson Pit #30, a 3.7-acre gravel pit overlooking the Kent Valley, and transformed it completely. Morris took out the undergrowth, molded and terraced the earth, and planted it with rye grass. A few blackened tree stumps were left along the rim of the pit, as a monument to the forest that once existed on the site.

Today, Untitled (Johnson Pit #30) continues to draw in visitors from within the community as well as those passing though. Step into the gently sloping amphitheater, and see if you can identify elements from the Peruvian and Persian designs that inspired Morris to create this powerful piece of art.

21630 37th Pl S, SeaTac, WA 98198

5. Tillamook Rock Lighthouse

A few hours' drive southwest of Mount St. Helens, off the northern end of Oregon's coast, you can see the legacy of another powerful force of nature. The Tillamook Rock Lighthouse stands atop a basalt sea stack a mile offshore, in the place where it once helped ships navigate dangerous waters.

"Terrible Tilly," as the lighthouse was known, began her story in 1878. Before construction even began, a mason surveying the site was swept out to sea and never seen again. But somehow, the location choice remained. The lantern was lit for the first time in 1881, and her watch began. Tilly endured the sea's wrath, even though a devastating storm in October 1934 that brought winds powerful enough to toss boulders. One of those boulders hit Tilly’s lantern room, destroying the lens within.

The Tillamook Rock Lighthouse and her keepers withstood the ravages of the sea for 77 long, windswept years. On September 1, 1957, lighthouse keeper Oswald Allik turned off the light one last time. In his final logbook entry, Allike thanked Tilly, writing, “Your purpose is now only a symbol, but the lives you have saved and the service you have rendered are worthy of the highest respect.”

From the shores of Ecola State Park, you can still see Tilly standing on her rock. If you have a few hours and a pair of hiking boots, there's an even better viewing point along the Tillamook Head Trail.

Cannon Beach Trail, Seaside, OR 97138

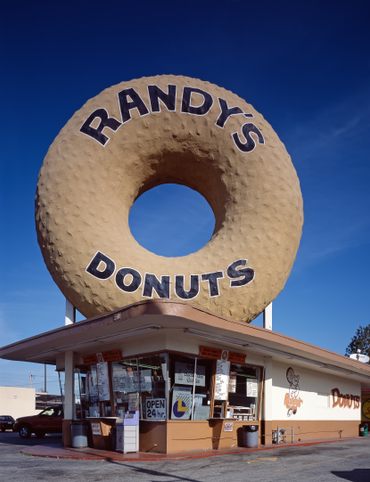

6. The Original Pronto Pup

While storms powerful enough to take a lighthouse out of service are rare, the rains of the Pacific Northwest are persistent and often have smaller casualties. In 1939, one of those casualties was George and Versa Boyington’s buns.

The husband and wife team ran a hot dog stand at Rockaway Beach, and a rainy Labor Day weekend had turned their stock of hot dog buns into a soggy mess. To keep wares from becoming seagull scraps, George came up with an unlikely idea that you might recognize from the county fair: dip the hot dog in batter and deep fry it. He dubbed his creation the Pronto Pup, and it was a hit. The “weiner dun in a bun” spread across the country, becoming a beloved staple at carnivals and festivals. Though “corn dog” has become the familiar nomenclature in many places, the Pronto Pup is distinct: It has a unique batter that lacks the sweetness found in most corn dog coatings.

In 2016, the Original Pronto Pup restaurant opened in Rockaway Beach, where it all began. The pups come in all varieties now, from Louisiana spice to vegetarian to a deep-fried dill pickle on a stick. All are dipped in signature Pronto Pup batter then fried to crispy, greasy perfection. You’ll know you’ve reached the right place when you see the 30-foot-long sausage on the roof.

602 S, US-101, Rockaway Beach, OR 97136

7. Octopus Tree

The steep cliffs at Cape Meares play host to roosting cormorants and peregrine falcons. The headlands' forests are home to elk and bears, and migrating whales can be spotted in the nearby waters. And among this fascinating fauna, an unusual tentacled being is one of the cape's most captivating sights. Instead of a central trunk, this Sitka spruce appears to have several trunks that branch out from a central base measuring nearly 50 feet around.

Known as the Octopus Tree, the rogue-rooted spruce is believed to be between 250 and 300 years old. How it came to have so many trunks has been debated. Some believe that it was shaped by natural conditions. Others have suggested that it is an example of a culturally modified tree, trained to grow into its unique shape by Indigenous people from the Northwest Coast tribes. Culturally modified trees have been documented throughout the Pacific Northwest, and often mark important ceremonial or burial sites.

Park at the Cape Meares State Scenic Viewpoint and take in the ocean breeze. Signs mark the trail that leads to the Octopus Tree.

Cape Meares Lighthouse Dr, Tillamook, OR 97141

8. Willamette Falls

The Willamette River flows north through some of the most fertile and abundant land in the Pacific Northwest. Rushing through the Oregon Coast range on one side and the Cascades on the other, the Willamette plummets abruptly straight down the height of a four-story building when it reaches Oregon City.

Willamette Falls is a horseshoe-shaped block waterfall caused by a basalt shelf in the river bottom. Its average flow is nearly a quarter of a million gallons a second, making it second largest waterfall by volume in the United States—outclassed only by Niagara.

On the east and west banks of the river, two paper mills and one of the oldest water-powered plants in the country once put that water power to use. Given the 40-foot drop that spans over 1,500 feet, a system of locks and canals was needed to allow logging and shipping vessels to pass. But as the local timber and paper industries waned, the canal system was converted to accommodate pleasure and fishing boats. By 2011 the system was deemed too expensive to keep running, and it has been shut down.

There are several viewpoints for the Willamette Falls located south of Oregon City along Highway 99E and Interstate 205. Choose your adventure: the 99E stop is closer to the falls, but the I-205 stop is located at a higher vantage point, so you can take in the surrounding scenery.

West Linn, OR 97045

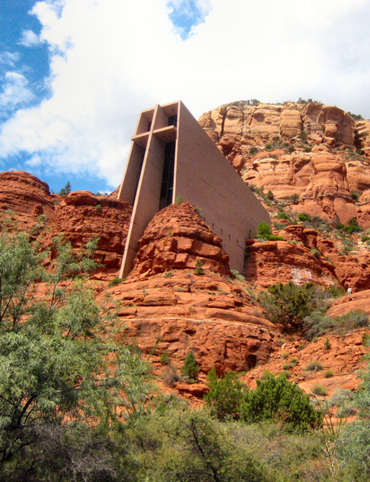

9. Camp Colton

There’s no more restful place to end your journey than Camp Colton. Babbling streams wind through groves of massive evergreen trees at this former sleepaway camp. The campus, which is located on 85 acres of lush green wilderness in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains, has been reimagined as a creative and peaceful gathering space.

The campgrounds are filled with thing to discover. As you wander through the sun-dappled woods, you might find a small creek or a hidden waterfall, or wander into an open meadow. Though much of its 85 acres are made up of this natural wilderness, Camp Colton has several historic buildings. The original kitchen and dining hall was built in 1935, and restored in 2017. There is a World War II-era chapel that was originally built for a U.S. Army camp near Corvallis. In 1948 the chapel was carefully dismantled, placed on a flatbed truck, driven 70 miles, and put back together board-by-board at Camp Colton.

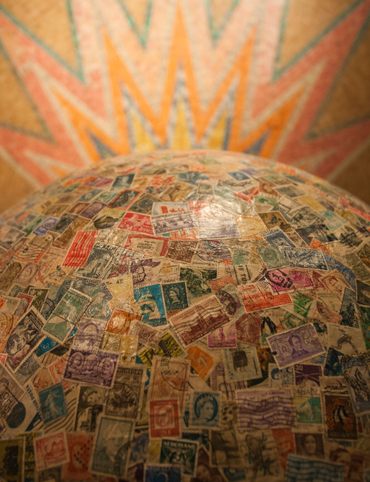

Camp Colton hosts artists and writers in residence, who are invited to live on the grounds while they produce new works, conduct research, or otherwise highlight the natural and cultural beauty of this part of Oregon. Right now, artists Cannupa Hanska Luger and Marie Watt are in residence while they produce a large-scale sculptural installation made of hand-decorated bandanas.

30000 S Camp Colton Dr, Colton, OR 97017

This post is sponsored by Nissan as part of Rogue Routes, a cross-country winter celebration of the rogue spirit --- of iconoclasts, innovators, and daredevils -- and the release of the 2021 Nissan Rogue through once-in-a-lifetime socially-distanced drive-in and livestream experiences. Discover more and check out the event lineup here.

Gastro Obscura’s 11 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Bangkok

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Rome

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Around the Great Lakes

10 National Parks That Are Perfect for a Road Trip

10 Out-of-This-World Places You Can Reach in Your Car

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Around Appalachia

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Down Highway 61

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Stops on an Alternative London Pub Crawl

The Explorer’s Guide to Joshua Tree National Park

The Explorer’s Guide to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Cosmic Colorado: A Stargazer’s Guide to the Centennial State

The Explorer’s Guide to Banff National Park

10 Wild Places That Define West Virginia’s Landscape

The Ultimate Guide to Hidden Red Rocks: 10 Secret Passageways, Artifacts, and Ghost Stories

The Explorer’s Guide to Williamsburg, Virginia

The Explorer’s Guide to the British Virgin Islands

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat, Drink, and Shop in Hong Kong

A Denver Guide for National Park Lovers

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Oaxaca

A Gastro Obscura Guide to Family-Friendly Dining in San Diego

The Explorer’s Guide to Outdoor Wonders In Maryland

The Secret Lives of Cities: Ljubljana

From Cigar Boom to Culinary Gem: 10 Essential Spots in Ybor City

The Explorer’s Guide to Wyoming’s Captivating History

A Nature Lover’s Guide to Sarasota: 9 Wild & Tranquil Spots

California’s Unbelievable Landscapes: A Guide to Nature’s Masterpieces

The Ultimate California Guide to Tide Pools and Coastal Marine Life

Explore California on Foot: Nature’s Year-Round Playground

Mardi Gras 9 Ways: Parades, Cajun Music, And Courirs Across Louisiana

The Explorer’s Guide to Winter in Germany

Ancient California: A Journey Through Time and Prehistoric Places

The Wildest West: Explore California’s Ghost Towns and Gold Fever Legacy

Sweet California: A Culinary Guide to Tasty Treats Across the State

Sea of Wonders: An Itinerary Through California’s Stunning Shoreline

10 Places to Taste Catalonia’s Gastronomic Treasures

Atlas Obscura’s Guide to Palm Springs

Atlas Obscura’s Guide to the 10 Most Mystifying Places in Illinois

10 Fascinating Sites That Bring Idaho History to Life

North Carolina's Paranormal Places, Scary Stories, & Local Haunts

Exploring Missouri’s Legends: Unveiling the Stories Behind the State’s Iconic Figures

These Restaurants Are Dishing Out Alabama’s Most Distinctive Food

A Gastro Obscura Guide to Los Cabos

9 Watery Wonders on Florida’s Gulf Coast

Discover the Surprising and Hidden History of Monterey County

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Eating Your Way Through Charlotte

Talimena Scenic Byway: 6 Essential Stops for Your Arkansas Road Trip

9 Amazing Arkansas Adventures Along the Scenic 7 Byway

The Explorer's Guide to Highway 36: The Way of American Genius

A Behind-the-Scenes Guide to DC’s Art and Music

9 Places Near Las Vegas For a Different Kind of Tailgate

10 Places to See Amazing Art on Florida's Gulf Coast

8 Reasons Why You Should Visit the Bradenton Area

A Music Lover’s Guide to New Orleans

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Sipping Wine in Catalonia

9 Hidden Wonders in the Heart of Kansas City

10 Unexpected Delights of Vermont's Arts and Culture Scene

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Eating Through Maine

The Gastro Obscura Guide to Asheville Area Eats

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to St. Pete/Clearwater

9 Hidden Wonders in Eastern Colorado

7 Places to Experience Big Wonder in Texas

8 Out-There Art Destinations in Texas

6 Ways To See Texas Below the Surface

9 Places to Dive Into Fresh Texas Waters

7 Ways to Explore Music (and History) in Texas

8 Ways to Discover Texas’ Rich History

The Explorer’s Guide to the Northern Territory, Australia

The Explorer's Guide to U Street Corridor

Gastro Obscura Guide to Southern Eats

Only In Delaware

The Secret History & Hidden Wonders of Charlotte, North Carolina

Exploring Colorado's Historic Hot Springs Loop

These 8 Arizona Ghost Towns Will Transport You to the Wild West

A Guide to Arizona’s Most Striking Natural Wonders

The Explorer's Guide to Hudson Valley, New York

Discover the Endless Beauty of the Pine Tree State

Travel to New Heights Around the Pine Tree State

8 Historical Must-Sees in Granbury, Texas

7 Creative Ways to Take in San Antonio’s Culture

Eat Across the Blue Ridge Parkway

6 Ways to Absorb Addison, Texas’ Arts and Culture

6 Ways to Take in the History of Mesquite, Texas

6 Ways to Soak Up Plano’s Art and Culture

9 Dallas Spots for Unique Art and Culture

7 Sites of Small-Town History in Waxahachie, Texas

6 Natural Wonders to Discover in Austin, Texas

Discover the Secrets of Colorado’s Mountains and Valleys

A Road Trip Into Colorado’s Prehistoric Past

A Feminist Road Trip Across the U.S.

All Points South

Asheville: Off the Beaten Path

Restless Spirits of Louisiana

Eat Across Route 66

18 Mini Golf Courses You Should Go Out of Your Way to Play

4 Underwater Wonders of Florida

6 Spots Where the World Comes to Delaware

Study Guide: Road Trip from Knoxville to Nashville

6 Wondrous Places to Get Tipsy in Missouri

Rogue Routes: The Road to Pikes Peak

Rogue Routes: The Road to Carhenge

4 Pop-Culture Marvels in Iowa

7 Stone Spectacles in Georgia

6 Stone-Cold Stunners in Idaho

8 Historic Spots to Stop Along Mississippi's Most Famous River

5 Incredible Trees You Can Find Only in Indiana

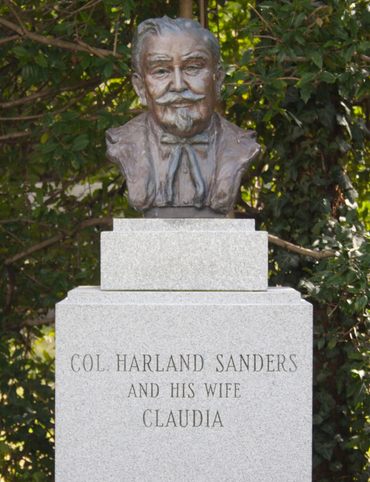

5 Famous and Delightfully Obscure Folks Buried in Kentucky

4 Wacky Wooden Buildings in Wyoming

7 Spots to Explore New Jersey’s Horrors, Hauntings, and Hoaxes

4 Out-There Exhibits Found Only in Nebraska

6 Sweet and Savory Snacks Concocted in Utah

12 Places in Massachusetts Where Literature Comes to Life

8 Places to Get Musical in Minnesota

8 Buildings That Prove Oklahoma's an Eclectic Art Paradise

9 Stunning Scientific Sites in Illinois

5 Strange and Satanic Spots in New Hampshire

8 Historic Military Relics in Maryland

5 of Colorado's Least-Natural Wonders

Rogue Routes: The Road to Sky’s the Limit

6 Hallowed Grounds in South Carolina

9 Rocking Places in Vermont

Knoxville Study Guide

Nashville Study Guide

Black Apples and 6 Other Southern Specialties Thriving in Arkansas

4 Monuments to Alabama’s Beloved Animals

The Dark History of West Virginia in 9 Sites

11 Zany Collections That Prove Wisconsin's Quirkiness

7 Inexplicably Huge Animals in South Dakota

6 Fascinating Medical Marvels in Pennsylvania

8 Places in Virginia That Aren’t What They Seem

7 Cool, Creepy, and Unusual Graves Found in North Carolina

7 of Montana's Spellbinding Stone Structures

9 of Oregon’s Most Fascinating Holes and Hollows

Take to the Skies With These 9 Gravity-Defying Sites in Ohio

9 Strange and Surreal Spots in Washington State

8 Watery Wonders in Hawaiʻi, Without Setting Foot in the Ocean

6 Unusual Eats Curiously Cooked Up in Connecticut

11 Close Encounters With Aliens and Explosions in New Mexico

10 Places to Trip Way Out in Kansas

The Resilience of New York in 10 Remarkable Sites

7 Very Tall Things in Very Flat North Dakota

8 Blissfully Shady Spots to Escape the Arizona Sun

On the Run: NYC

On the Run: Los Angeles

9 Surprisingly Ancient Marvels in Modern California

10 Art Installations That Prove Everything's Bigger in Texas

6 Huge Things in Tiny Rhode Island

7 Underground Thrills Only Found in Tennessee

Sink Into 7 of Louisiana's Swampiest Secrets

7 Mechanical Marvels in Michigan

11 Wholesome Spots in Nevada

7 Places to Glimpse Maine's Rich Railroad History

11 Places Where Alaska Bursts Into Color

9 Places in D.C. That You're Probably Never Allowed to Go

2 Perfect Days in Pensacola

Rogue Routes: The Road to the Ice Castles

Taste of Tucson

North Iceland’s Untamed Coast

Hidden Edinburgh

Hidden Haight-Ashbury

The Many Flavors of NYC’s Five Boroughs

Hidden French Quarter

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Motown to Music City Road Trip

Gulf Coast Road Trip

Hidden Coachella Valley

Highland Park

Venice

L.A.’s Downtown Arts District

Hidden Trafalgar Square

Secrets of NYC’s Five Boroughs

Mexico City's Centro Histórico

Hidden Hollywood

Hidden Times Square

Summer Radio Road-Trip

Amsterdam

Buenos Aires

Chicago

Detroit

Lisbon

Miami

Queens

San Diego