The Atlas Obscura Guide to

Hidden Edinburgh

Crowds clog Edinburgh's Royal Mile, the main artery between Edinburgh Castle and Holyrood Palace. The road is dotted with stores selling Nessie trinkets and lined with bagpipers and street performers pulling off dazzling tricks. But look beyond the tartan tourist traps, and you’ll discover tucked-away gardens, remnants of the city’s medieval past, and much more.

1. The Witches’ Well

You’ll start your day at the Edinburgh Castle Esplanade, the large, flat area in front of the fortress’s gatehouse. It now teems with tourists, but once served a more sinister purpose. Witch hunts plagued Europe from the 15th through 18th centuries, when thousands of alleged witches—mostly women—were burned at the stake or hanged. In the 16th century, more women were murdered at this site than anywhere else in Scotland.

A memorial to the people killed at this spot sits on the cobbled street at the top of the Royal Mile, but it's easy to miss. Look toward the wall of the attraction called the Tartan Weaving Mill and Experience, and you’ll notice a cast iron fountain and plaque. Sir Patrick Geddes, a philanthropist known for his innovative thinking in urban planning and sociology, commissioned artist John Duncan to create the fountain in 1894. Examine the fountain’s details, and you’ll see the image of a snake ensnaring the witches’ heads, as well as foxglove, a plant used for both medicinal purposes and poison. A hole beneath the snake’s head once spouted water, but the fountain is now dry.

555 Castlehill, Edinburgh, Scotland EH1 2ND

2. Deacon Brodie’s Wardrobe

Duck into the alley called Lady Stair’s Close, and you’ll find a small museum in a 17th-century building dedicated to three legendary writers: Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Louis Stevenson. Take the stairs down to the Stevenson room, where you’ll notice a handsome mahogany cabinet standing against the wall. At first, the piece of furniture seems out of place among Stevenson’s more obviously intriguing effects, which include a ring gifted to him by a Samoan chief. But the wardrobe, which once stood in the writer’s childhood bedroom, was made by none other than Deacon Brodie, the legendary craftsman believed to have inspired the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. This piece of furniture is a surprising entry point into a wacky historical anecdote about the famous figure.

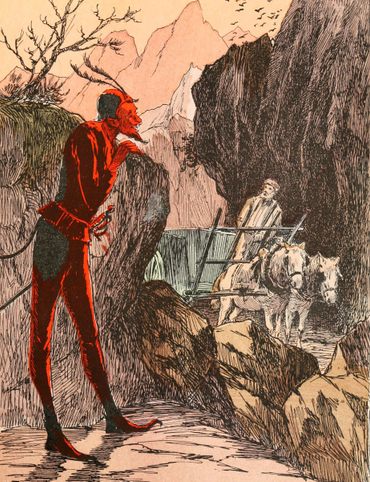

Brodie, whose name graces various pubs, was an esteemed 18th-century socialite. A locksmith and master cabinetmaker by trade, he was named Deacon of the Incorporation of Wrights, earning him power within the woodworking guild and a spot on the city council. But unknown to his admirers, the esteemed tradesman had a shadier side: He’d make copies of keys to his wealthy clients’ houses so he could later sneak into their homes and rob them. After a failed robbery attempt in 1788, Brodie’s darker tendencies were revealed, soiling his reputation as a morally respectable man.

Lady Stair's Close, Edinburgh, Scotland EH1 2PA

3. Riddle's Court

Constructed in the 1590s, Riddle’s Court is one of the oldest buildings on the Royal Mile. It’s lived many lives and seen several renovations during its four centuries of existence, serving stints as a merchant’s mansion, the setting of a royal banquet, and even a student dormitory. For more information about the building's history, pop into the Patrick Geddes Centre near the lobby. If you ask nicely, reception may let you peek into the nearby bathroom, where you’ll find a 21st-century toilet plunked right next to a gaping 16th-century fireplace and bread oven, relics of the old kitchen.

To explore the rest of the building—including walls, staircase fragments, and other architectural ghosts lingering among modern construction—you’ll have to take a guided tour. These are typically offered on Fridays and can be booked via Eventbrite.

To rest like a royal, you can reserve a night or two in the King’s Chamber, the room where King James VI of Scotland and his wife, Anne of Denmark, once held a dinner party for the Duke of Holstein. You’ll sleep beneath a ceiling decorated with paintings created for the 1598 feast, including emblems of a thistle and double-headed eagle representing the Crown of Scotland and the Holy Roman Empire.

322 Lawnmarket, Edinburgh, Scotland EH1 2PG

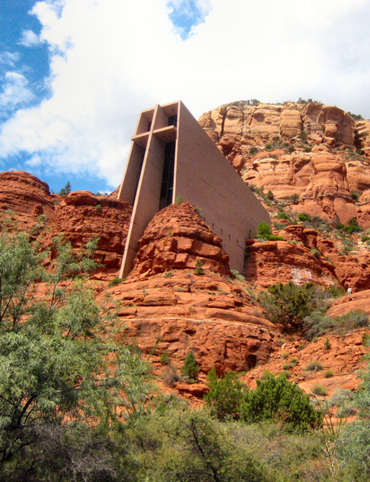

4. Magdalen Chapel's Stained Glass

Detour down Victoria Street—and as you do, be sure to snap a photo of the colorful facades hugging the edge of the curved road. Instead of turning right onto the Grassmarket, head left down the Cowgate. There, nestled among the hostels and night clubs, is Magdalen Chapel. Built in 1541 for the Incorporation of Hammermen, the chapel is now the headquarters for the Scottish Reformation Society. Enter the unassuming church, and you’ll find a bright, airy interior hiding behind its grungy outer walls. Inside, capped by a light-blue ceiling and illuminated by the stray beam of Scottish sunlight, is an unexpected window into the past.

Magdalen Chapel houses the only significant stained glass that survived the Scottish Reformation in its original location. During the Reformation, religious art was destroyed by iconoclastic groups in favor of less-extravagant decor. But it’s believed these four stained-glass roundels were spared because they don’t depict religious imagery. Instead of Biblical scenes or saints, the glass shows heraldic designs representing the Royal Arms of Scotland, Mary of Guise (the mother of Mary Queen of Scots), and the husband and wife Michael MacQuhane and Janet Rynd, who commissioned the chapel. These rare relics, though dulled by age, draw the eye to the chapel’s center window, just as they have for nearly five centuries.

41 Cowgate, Edinburgh, Scotland EH1 1JR

5. Overlooked Sights in Parliament Square

Parliament Square is dominated by Saint Giles’ Cathedral. Head to the southeastern part of the structure, where you’ll step into a small chapel adorned with spectacular woodwork. The Thistle Chapel is a 20th-century addition to the 12th-century cathedral. It’s home to the chivalric Order of the Thistle, and knights’ coats of arms line the walls, surrounded by other intricate carvings. Hiding among these sigils and images of the natural world are three angels playing bagpipes—a detail charming enough to inspire the name of the restaurant across the street, Angels and Bagpipes. Eagle-eyed visitors to the chapel will spot two wooden angels—one above the top-right corner of the door, the other wedged in the corner across from the entrance—and a stone one overlooking one of the windows.

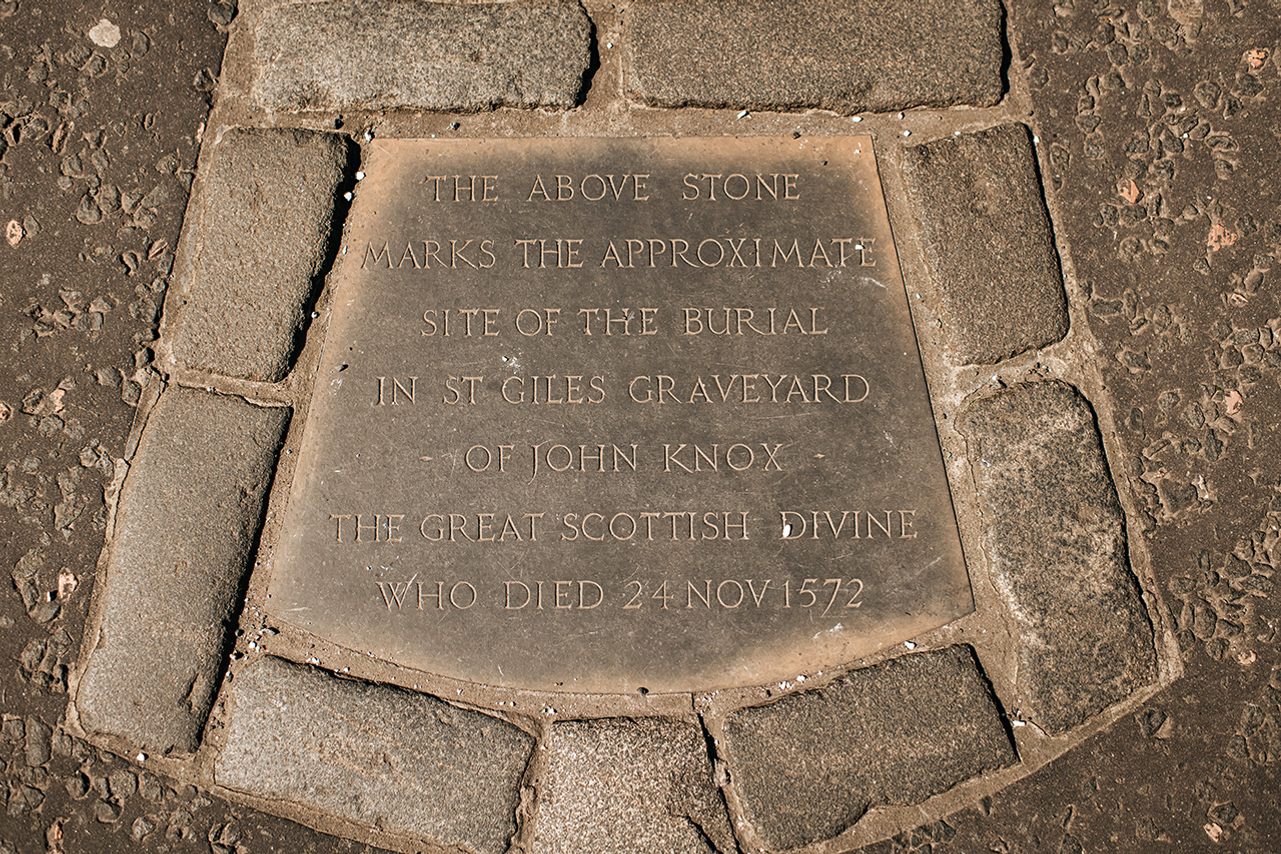

Once you’ve left the cathedral, pop into its back parking lot and go to space number 23. If a car isn’t parked there, you’ll see the rather unceremonial burial place of John Knox, one of the country’s most prolific and influential religious figures. Knox was a 16th-century preacher and key proponent of the Protestant Reformation. It’s said Knox wanted to be buried within 20 feet of Saint Giles, and he was interred in what was once a proper graveyard. After the site was tarmacked over, a plaque was installed to mark the approximate location of his now-lost grave.

Next, turn your attention upward, and you’ll see an equestrian statue towering atop a plinth in the square, with the cathedral in the background. This life-sized effigy of Charles II riding a trusty steed was erected in 1685, the year of the king’s death. It’s the oldest statue in Edinburgh, and is believed to be the U.K.'s oldest equestrian statue made out of lead.

Parliament Square, Edinburgh, Scotland

6. Underground Vaults

Continue around Saint Giles’ until you’ve made your way back to the Royal Mile. You’ll arrive at the Mercat Cross, a Victorian-era replica of the medieval market cross, which denoted the location of a market where important announcements were made. But you’re not here to listen to any government proclamations. These days, the Mercat Cross is the meeting point for the Blair Street Underground Vaults tours, which descend into a forgotten world that once thrived beneath the South Bridge (make sure you’ve booked your Historic Underground ticket in advance).

When the bridge was completed in 1788, the businesses that originally lined the overpass put its 19 vaults to good use. Cobblers and smelters transformed the caverns into workshops, merchants used them as storage spaces, and pubs even packed patrons into the dark quarters. But less than a decade after the vaults opened, the businesses began to abandon them because the bridge’s faulty seal caused leaks. Brothels, gambling pubs, and unlicensed distilleries soon flourished in the secluded spaces. Edinburgh’s poorest residents also crammed into the tight chambers, wedging entire families into a single windowless room.

In a mid-19th century effort to evict the unsanctioned residents, the city filled the vaults with rubble and sealed them shut. They remained forgotten until the 1980s, when they were accidentally rediscovered when Scottish rugby player Norrie Rowan found a tunnel that led to them. Today, you can carefully traipse through the vaults’ uneven, sloping terrain, as your tour guide’s torch lights the way. Once you’re back above ground, you’ll pass through a small exhibition space containing a smattering of objects found within the vaults, including a broken chamber pot and a child’s glass pistol toy.

High St, Edinburgh, Scotland EH1 1RF

7. Snack Like a Scot

The Clamshell, a takeaway joint, offers a fast-food spin on haggis, Scotland’s national dish. Boiled sheep stomach stuffed with seasoned oats and offal is so beloved, it once inspired the country’s renowned poet Robert Burns to pen a poem. At the Clamshell, though, haggis gets the deep-fried treatment. The crispy orbs of sheep innards come drizzled with brown sauce and plopped atop a bed of chunky chips. Be sure to wash down your salty meal with a cup of Irn-Bru, the citrusy soda that’s more popular in Scotland than Coca-Cola. The fizzy drink tastes like a concoction of cream soda and artificial orange flavor—and some sippers even claim to detect a hint of rust. The Clamshell doesn’t offer sit-down dining, so you’ll have to tuck in on the go.

148 High St, Edinburgh, Scotland EH1 1QS

8. The Scotsman Steps

Wind down Cockburn Street, a postcard-worthy road that connects the Royal Mile to Waverly Station, and turn right down Market Street. You’ll come across a stairwell that links Market Street back up to the North Bridge. Today, these stairs are an often-unnoticed work of public art, constructed from marble from the world’s major quarries. But this wasn’t always the case.

The original stone and concrete steps, 104 in total, were constructed in 1899 alongside the Scotsman building—a newspaper’s former home that now serves as a hotel. By the early 21st century, the passage had fallen into disrepair. People took to using it as a public toilet, their urine mixing with the trash that littered the space. In 2011, artist Martin Creed cooked up a new art project to revive the stairwell and give it a marble makeover. Creed used different stone to create each step, and the result is a cascading medley of pigments, with reddish purples, deep greens, and blush hues from places as far away as Turkey, Slovenia, Bosnia, and Bolivia.

Scotsman Steps, Edinburgh, Scotland EH1 1QG

9. St Cecelia's Hall

Turn left down Niddry Street and enter St Cecilia’s Hall, the country’s first building of its kind. The Edinburgh Musical Society built the hall in 1762, but sold it at the beginning of the 19th century after concert-goers began opting to visit the New Town instead—the area that went up in the 18th century, when wealthy people got sick of living in cramped, destitute quarters in the Royal Mile. The University of Edinburgh bought the building in 1959 and restored the concert hall to its original rounded shape, painting its walls pleasant shades of pink.

There’s plenty more to see beyond the rosy room. The upper level, which is where you’ll find the concert hall, also houses the Raymond Russell Collection of Early Keyboard Instruments. These centuries-old keyboards are adorned with scenic paintings, and span two rooms. You’ll find harpsichords, clavichords, spinets, virginals, and a pianoforte that date from the 16th through 18th centuries. Some of the instruments bear scars from their past lives, with the paint on their fronts rubbed away by the dresses of the ladies who once stood before them.

50 Niddry St, Edinburgh, Scotland EH1 1LG

10. Tweeddale Court Sedan Chair House

Step into Tweeddale Court, and you’ll notice a shed-like structure jutting out from the western wall. This tiny building is believed to be a Georgian-era sedan chair house, a storage space for the human-powered carts that ferried Edinburgh’s wealthy residents around the Old Town. This mode of transit dates back to the days when the Royal Mile wasn’t the picturesque tourist thoroughfare it is today. People crammed into the closely built tenement buildings, chucking waste from their chamber pots onto the narrow streets below with a hearty cry of “gardyloo!” Rather than slosh through the sludge of sewage pooling on the cobblestones, wealthier people would climb into a tiny wooden compartment held aloft by two long poles. A pair or two of chairmen, usually from the Highlands, would then cart riders to their destinations. By the middle of the 19th century, the city’s sanitation had improved, and sedan chairs had fallen out of fashion. You won’t see any sedan chairs here today, but head a bit farther down the Royal Mile, and you’ll come across one in the Museum of Edinburgh.

Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh, Scotland

11. Museum of Edinburgh Old Town Models

The canary-yellow Museum of Edinburgh is a trove of treasures that reveal the city’s past. Among the culinary artifacts, pottery exhibits, and centuries-old human bones are a few models of the Old Town that provide a historic bird's-eye view of the road you’ve just walked.

Models constructed in the 1950s show the Old Town and the Canongate, which was once a separate burgh, as they looked at the end of the 16th century. Gaze down at the glass case, and you’ll spot familiar structures like Saint Giles’ poking up among the clusters of buildings crowding the High Street, many of which no longer exist. The model of the Canongate is much less dense, with large pockets of space surrounding the buildings toward the foot of the Royal Mile.

For a more rustic interpretation of the past, look at the museum’s second model of Edinburgh as it was 500 years ago. This wooden, Victorian-era depiction of the city was displayed at the 1886 International Exhibition of Industry, Science, and Art. You’ll see the Flodden Wall, built in 1513, wrapping around the city. To the north of the Old Town lies a streak of blue representing the Nor’ Loch, an artificial lake that was drained in 1821 during the construction of the Princes Street Gardens.

142-146, Canongate, Edinburgh, Scotland EH8 8DD

12. Book Sculptures at the Scottish Poetry Library

Step into the Scottish Poetry Library and head toward the main desk. There, protected within a glass case, stand four paper sculptures. One shows a gnarled tree sprouting from the cover of a book, its delicate paper branches draping downward. The artwork, titled “Poetree,” was the first of the original 10 Edinburgh book sculptures to mysteriously appear across the city in 2011. Over the next few months, similar sculptures materialized at various cultural institutions, garnering international attention. “Poetree” arrived at the Scottish Poetry Library in 2011, gifted as a response to the cutbacks and closures plaguing libraries. Its creator remains anonymous, though her work continues to pop up throughout Edinburgh.

5 Crichton's Cl, Edinburgh, Scotland EH8 8DT

13. Dunbar’s Close

Cross the street and duck into Dunbar’s Close, and you’ll soon feel as though you’ve left the city entirely. There, along the western wall of the Canongate Kirk, is a meticulously manicured oasis. Though the garden was built in the 1970s, it was designed with a 17th-century aesthetic in mind. You’ll first step into a section where the path meanders between the shrubbery, shaded by trees. Keep going, and you’ll see six yew plots lining the path to your right, with a lollipop-shaped holly standing in the center of each. To your left, conical shrubs tower over beds of flowers. Fig and rosemary crawl across the western wall, and honeysuckle and jasmine climb the trellises. The air is hushed here, and the city’s din dimmed. Benches against the walls provide ample opportunities to marinate in the serenity before stepping out to brave the crowds again.

137 Canongate, Edinburgh, Scotland EH8 8BW

14. Sanctuary Stones

Holyrood Palace stands at the foot of the Royal Mile. Look at the pavement near the entrance, and you’ll notice a row of three brass letter “S”s. These shiny symbols were placed on the cobblestones to mark the boundary of a five-mile area once known as Abbey Sanctuary. Those attempting to evade their debt creditors could seek refuge within its confines. Food and housing were on offer, too—though with a heftier price tag than you’d find in the Old Town. People could stay in the sanctuary indefinitely, and could even leave on Sundays without fearing retaliation from their collectors.

After the law changed in 1880, debtors could no longer be chucked behind bars, rendering the sanctuary obsolete. Queen Victoria had many of the area's old buildings demolished, though one still stands and now serves as a gift shop. Peruse the store in search of a Scottish souvenir or treat, or turn right toward Holyrood Park, where you can hike up the crags or its extinct volcano for breathtaking vistas of the Old Town.

Abbey Strand, Edinburgh, Scotland EH8 8DU