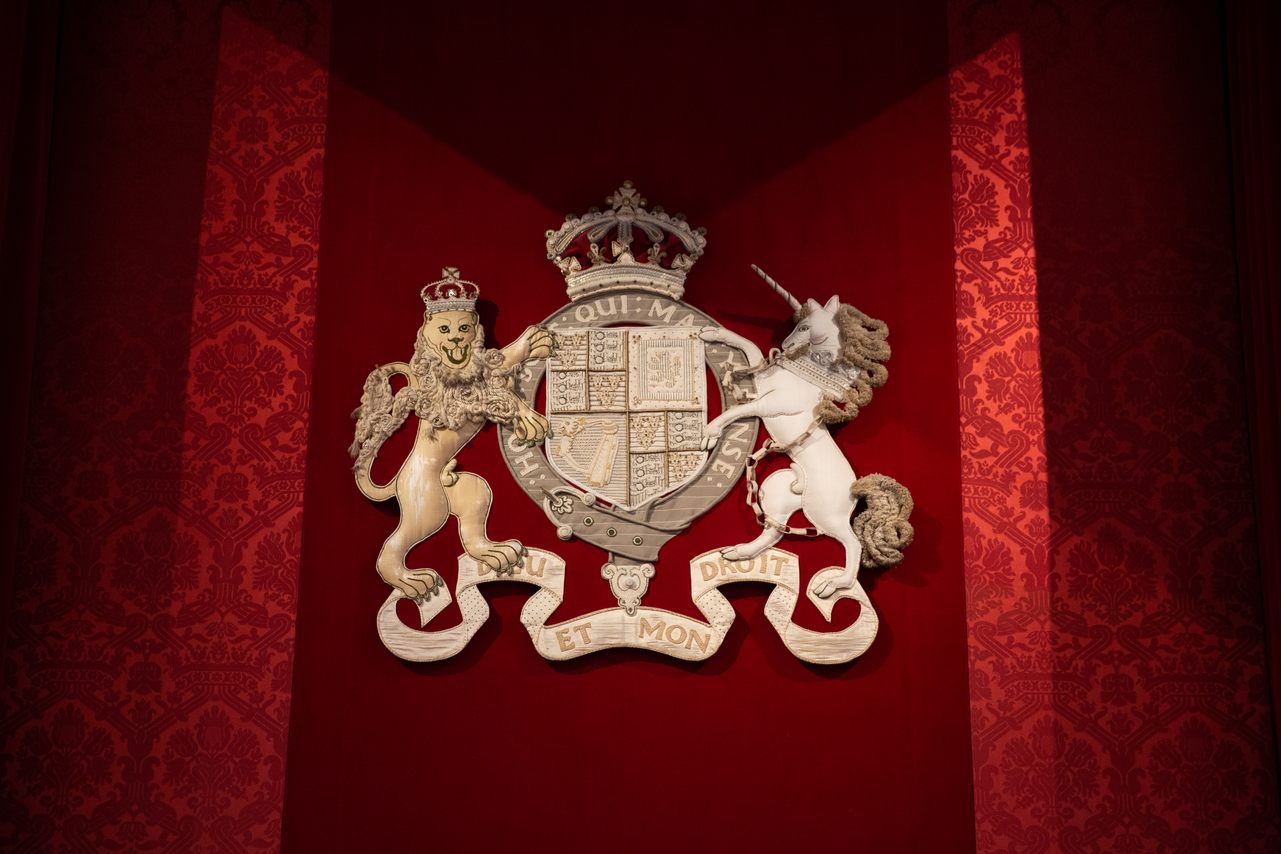

1. The Rubens Ceiling at the Banqueting House

Your day begins beneath one of the last things Charles I of England saw before his execution in 1649—a masterpiece by Flemish artist Peter Paul Rubens. Grab a free audio guide and sink into one of the plush beanbag chairs scattered throughout this first-floor room at the Banqueting House, where you’ll lounge below a set of canvases set snugly into the ceiling.

Charles commissioned the sumptuous ceiling in what was then part of Whitehall Palace, the main royal residence, to honor his father, James I. The three main canvasses glorify the monarchy and the divine right of kings, depicting the unification of England and Scotland, the reign of James I, and the king rising to Heaven on the back of an eagle. Architect Inigo Jones designed the hall’s ceiling to be a perfect frame for the artwork, creating a beamed design with blank shapes the paintings could fit tightly inside. But when Rubens’s and Jones’s assistants unrolled the artwork, they realized there’d been a slight snafu. The scrolls’ dimensions didn’t match those of the ceiling, thanks to a measurement mix-up caused by England and Belgium using a different standard length for a foot. To get the canvasses to fit, the assistants had to give them a careful trim.

Charles I’s throne on the far end of the room offered him a prime vantage point for contemplating the images and their meanings. The ceiling was also one of his final sights. After losing the Civil War to the Parliamentarians, Charles exited out a nearby window (which no longer exists), and stepped onto the scaffold, where he was beheaded.

Whitehall, London, England, United Kingdom

2. A Nose for Details

Walk beneath the northernmost opening of Admiralty Arch, and you may notice a small nub hiding in plain sight about seven feet above the ground. It’s a nose, and its presence has puzzled pedestrians for years.

The mysterious, out-of-place nose is steeped in local lore. One popular myth claims it was placed there as a nod to the Duke of Wellington, who was known for a particularly prominent one. Another urban legend says the nose was a spare part for Trafalgar Square’s centerpiece feature, Nelson’s Column. According to this tale, people were concerned the statue would be damaged when it was lifted to its perch, so a spare schnoz was stashed on the arch, where it remained hidden for decades.

It wasn’t until 2011 that the true origin of the enigmatic nose was sniffed out. It was one of several noses created by artist Rick Buckley in 1997 as part of a project criticizing CCTV and the spread of a “Big Brother” society across Britain. Buckley made 35 plaster casts of his own honker and placed them “under the nose” of officials in well-trafficked areas and on prominent buildings. Today, it’s said that seven noses remain stuck to structures around London’s Soho neighborhood.

The Mall, St. James's, London, England, United Kingdom

3. Surprises in the Square

Now, turn your attention to Trafalgar Square itself. Take a good look at the lions guarding the fountains, and you’ll notice the ferocious felines’ paws actually look like they belong to house cats (the sculptor wasn’t familiar with lions). Traipse over to the southeast corner of the square, and you’ll see something that looks like a lamp post with a door in it. This strange structure was once London’s smallest police station. A single officer could cram inside it and keep an eye on crowds at this popular protesting spot. If you peek inside today, though, you’ll only spot brooms, as it’s now used for storage.

Next, head to the National Gallery. Turn your gaze to the ground as you walk up the stairs, and you’ll notice a series of plaques containing the official imperial standard units of measurements, the system used throughout the British Empire. Thousands of tourists trod over these tablets each day, often unaware they’re stepping on bits of history.

Once you’re inside the National Gallery, make your way to Room 8. There, hiding in a Mannerist masterpiece, is a pop culture surprise. Agnolo Bronzino painted "An Allegory with Venus and Cupid" for King Francis I of France in the 16th century. Hundreds of years later, American-born animator Terry Gilliam wandered past the painting while seeking inspiration for the comedy series “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.” Cupid’s foot caught his eye, and became the basis for the iconic Monty Python foot that stomps from the sky and squashes scenes beneath its cartoon toes.

Trafalgar Square, London, England, United Kingdom

4. Jean Cocteau Murals at the Church of Notre Dame de France

Venture toward Leicester Square and into the unusually shaped Church of Notre Dame de France, whose round interior once displayed panoramas. The hushed, hallowed space offers a refuge from the packs of people shuffling around outside. Look to the left-hand side of the church, where you’ll spot three colorful murals covering the walls of a glass-protected enclave.

The church was consecrated in 1861 as a spiritual haven for the area’s French community. After much of the original building was destroyed during World War II, French cultural attaché René Varin reached out to various French artists to help create a space that would celebrate their homeland. Poet, artist, writer, and filmmaker Jean Cocteau answered the call. He traveled to London and set to work, spending a week holed up behind a privacy barrier. The final result is a set of striking murals showing the Annunciation, Jesus's crucifixion, and Mary's assumption into Heaven. Take a good look at the crucifixion scene, and you’ll notice Cocteau has given himself a cameo.

5 Leicester Place, London, England, United Kingdom

5. Booksellers' Row

There’s a good reason this dreamy little 17th-century lane was dubbed “Booksellers’ Row.” Stroll down Cecil Court, and you’ll pass dozens of secondhand bookstores and antiquarian shops. You can pop into the stores lining the street to peruse rare maps, first-edition books, esoteric goods, and unique art and jewelry. Some of the businesses display portions of their stock outside their Victorian facades, making it easy to rifle through bins of prints or flip through various books. The pedestrian street is as historical as it is charming—Mozart lived here when he was eight years old, and over a century later, the lane featured heavily in early British cinema.

Once you’ve wandered through Cecil Court, nip across St. Martin’s Lane and peek down Goodwin’s Court, a picturesque alley that looks plucked from the pages of a Dickens novel.

Cecil Court, London, England, United Kingdom

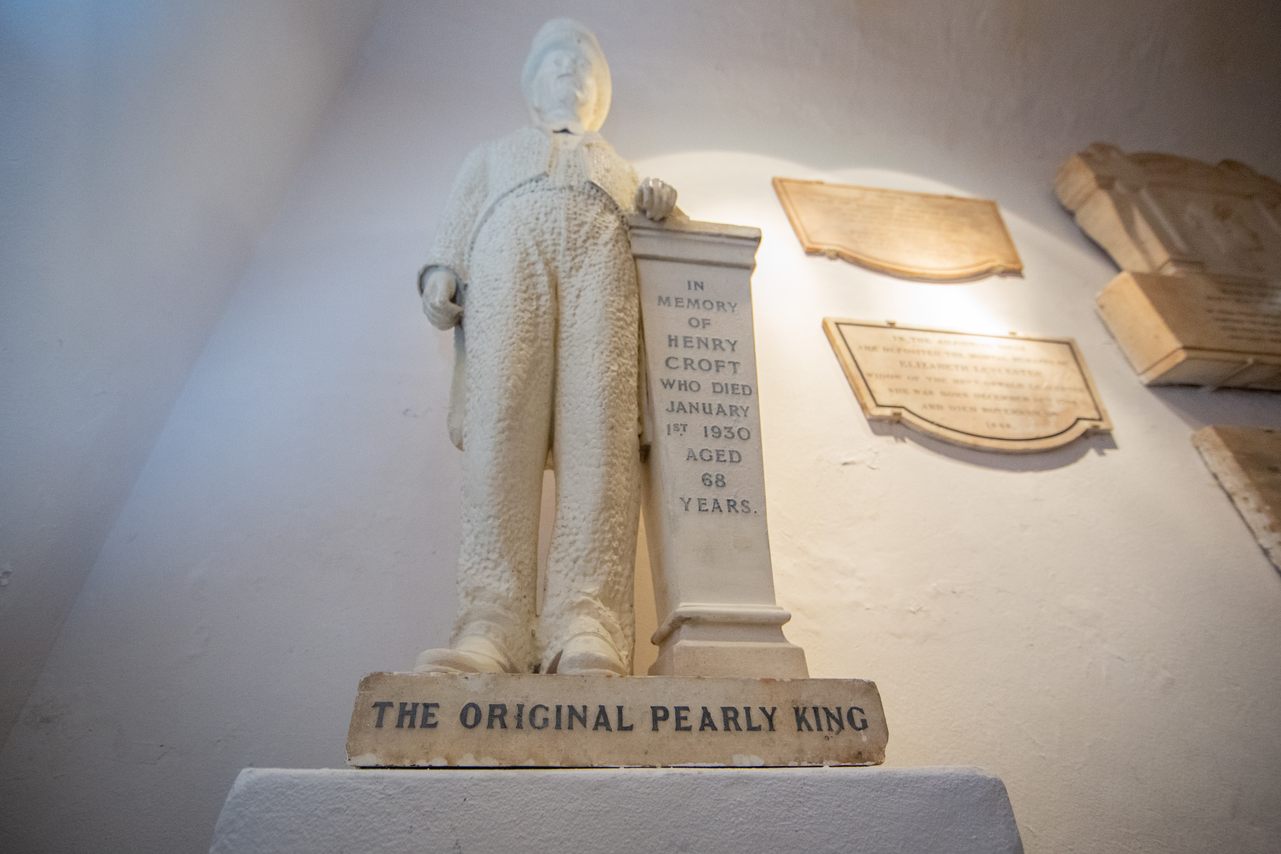

6. The Gravestone of the First Pearly King

Churches have stood on this site since medieval times. The most recent is St. Martin-in-the-Fields, built in 1726, which sits along the eastern edge of Trafalgar Square. Descend into its labyrinthine crypt, past the cafeteria-style cafe, and turn right down the narrow hallway. You’ll pass an old whipping post on your way to the second, quieter seating area. Swing left, and you’ll find yourself staring down another slim passage lined with old gravestones. Against the far wall, you’ll spot a life-sized statue of Henry Croft, known as the “First Pearly King.” A street sweeper by profession, Croft would don a pearl-covered suit while raising money for charity, using the glitzy garb to attract attention to himself. Though he died in 1930, the tradition outlived him. Today, you can still spot “Pearlies” out and about in London, wearing shiny attire and raising funds for a cause.

Trafalgar Square, London, England, United Kingdom

7. An Ode to Oscar Wilde

Head east down Duncannon Street and take a brief detour down Adelaide Street. There, you’ll spot the first public monument to Oscar Wilde located outside Ireland. "A Conversation with Oscar Wilde," created by Maggi Hambling and installed in 1998, is indeed a conversation starter. Wilde’s head, which looks like a squiggly glob of spilled spaghetti, emerges from a coffin-shaped base. His equally abstract hand clutches at nothing, as the cigarette he originally held was repeatedly stolen. The sculpture also serves as a bench, so feel free to take a seat.

3 Adelaide St, London, England, United Kingdom

8. The World’s Oldest Family-Run Magic Shop

Once on Strand, keep an eye out for a staircase between a Starbucks and Paperchase. Go down and enter an underground arcade. Walk along the sticky floor speckled with globs of old gum, then swing right, and you’ll arrive at the world’s oldest family-run magic emporium.

Davenports Magic Shop opened in 1898, and has something for everyone, from newbies buying their first deck of cards to veterans with more than a few schemes up their sleeves. Browsing its stock is like dipping your hand into a magician’s hat—you never know what wonders you’ll uncover. The shelves lining the small, red-carpeted store are stuffed with all sorts of books, out-of-print editions, DVDs, cards, and other tools of the trade.

7 Charing Cross Underground Arcade, The Strand, London, England, United Kingdom

9. Charing Cross Storm Tree

On October 16, 1987, the “Great Storm” tore through London, where winds topped 98 miles per hour and knocked down 250,000 of the city’s trees. Twenty-two human fatalities were reported in England, France, and the Channel Islands, and England lost a total of 15 million trees that night. In the aftermath, the Evening Standard newspaper raised £60,000 to plant new trees in each of London’s 32 boroughs and the City of London. This English oak was planted a year after the terrible storm. Now, commuters rushing to and from Charing Cross station likely pass through the living monument’s dappled shadow without a second glance. A plaque attached to a nearby pillar tells the tree’s history, and a second plaque installed in 2017 honors Angus McGill, the newspaper columnist who spearheaded the fundraising effort.

Villiers St, London, England, United Kingdom

10. The York Water Gate

Head down Villiers Street toward the Victoria Embankment Gardens. There, you’ll spot an ornate, Italianate water gate sitting atop a bed of dirt and greenery. Before the Victoria Embankment was constructed in 1862, changing the river’s course as it modernized the city's sewer system and reduced traffic along the Strand, this gate sat on the northern edge of the River Thames for more than 200 years. It served as a waterfront entrance to the esteemed York House mansion, one of the fancier homes that dotted this stretch of prime riverside real estate. Boats would pull right up to its stairs, depositing passengers in the property’s back gardens. Departing guests could huddle beneath the gate’s two arches while waiting for their watercraft to arrive. Today, the gate is surrounded by solid ground, more than 300 feet from the shore. It’s a relic of the river’s old path and a reminder of the now-demolished mansion it once served.

Watergate Walk, London, England, United Kingdom

11. Century-Old Optical Museum

Tucked in the basement of the College of Optometrists is the British Optical Association Museum, home to a curious collection of ocular objects. The now-defunct British Optical Association opened the museum—the world's oldest of its kind—in 1901 to record the development of corrective eyewear, and its collection has continued to grow. Though thousands of visitors come to Trafalgar Square every day, only about 1,000 guests dip inside this appointment-only museum each year.

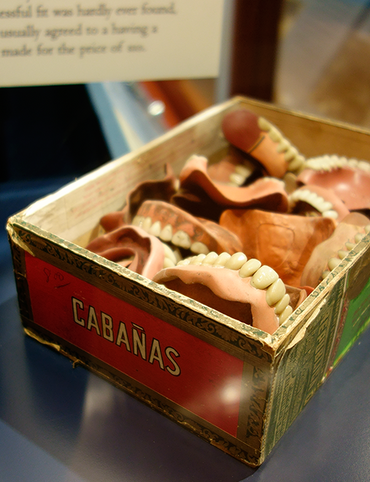

A guided tour of the museum’s two rooms reveals a unique feast for the eyes, as well as a crash course in all things optical. With the collection’s curator as your guide, your introduction comes from the man who knows it best. Glasses and glass eyeballs gaze at you from beneath their cases, and you’ll find shelves stuffed with eye-related art and artifacts, including an eye of Horus. Tacked to the wall, there's a plaster cast of a 15th-century nun wearing spectacles, a replica of a real corbel from an English church. Look for the plush chicken donning “pecktacles,” frames industrial farmers once used to keep the birds from pecking at each others’ eyes.

42 Craven St, London, England, United Kingdom

12. The Upstairs Apartment at the Sherlock Holmes Pub

This watering hole serves as both a restaurant and an ode to London’s most famous detective. The pub is crammed with props related to the books and movies starring Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s superstar—think pipes and vials—and there’s even a taxidermy “hound of Baskerville” hanging on the wall near the bathrooms. Go upstairs, and you’ll find a life-sized replica of the apartment Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson shared, with immaculate details ripped straight from the novels. A bear rug sprawls across a floor crowded with clutter, making it look as though two messy sleuths still live in the space.

The collection was originally curated by the Westminster Library and displayed as part of the 1951 Festival of Britain. The pub’s owners acquired it a few years later, and it became the crux of the eatery’s identity. Now, behind glass windows, the storybook apartment is a stark contrast to the chatter and clinks of cutlery on the other side of the panes, where diners tuck into fish and chips, burgers, baked potatoes, and other classic pub grub.

10 Northumberland St, London, England, United Kingdom

13. Rooftop Tipples at the Trafalgar St. James

You’ll end your adventure at the Trafalgar St. James. Take the lift to the seventh floor and step onto the patio of its rooftop bar for a birds-eye view of the square. The covered portions will keep you dry even on a soggy day, and outdoor heaters keep the space cozy during the drearier months. From this height, you’ll also have an unusual view of Nelson’s Column. Rather than standing in its shadow and craning your neck to see the sandstone statue that crowns the pillar, the rooftop bar gives you a prime view of Admiral Nelson’s profile. Grab an after-dinner digestif and drink it all in—and watch the tourists bustling by the hidden wonders you’ve already explored.

7th Floor, 2 Spring Gardens, London, England, United Kingdom

Special thanks to James Manning, Feargus O'Sullivan, and Luke J. Spencer

Gastro Obscura’s 11 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Bangkok

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Rome

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Around the Great Lakes

10 National Parks That Are Perfect for a Road Trip

10 Out-of-This-World Places You Can Reach in Your Car

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Around Appalachia

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Down Highway 61

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Stops on an Alternative London Pub Crawl

The Explorer’s Guide to Joshua Tree National Park

The Explorer’s Guide to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Cosmic Colorado: A Stargazer’s Guide to the Centennial State

The Explorer’s Guide to Banff National Park

10 Wild Places That Define West Virginia’s Landscape

The Ultimate Guide to Hidden Red Rocks: 10 Secret Passageways, Artifacts, and Ghost Stories

The Explorer’s Guide to Williamsburg, Virginia

The Explorer’s Guide to the British Virgin Islands

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat, Drink, and Shop in Hong Kong

A Denver Guide for National Park Lovers

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Oaxaca

A Gastro Obscura Guide to Family-Friendly Dining in San Diego

The Explorer’s Guide to Outdoor Wonders In Maryland

The Secret Lives of Cities: Ljubljana

From Cigar Boom to Culinary Gem: 10 Essential Spots in Ybor City

The Explorer’s Guide to Wyoming’s Captivating History

A Nature Lover’s Guide to Sarasota: 9 Wild & Tranquil Spots

California’s Unbelievable Landscapes: A Guide to Nature’s Masterpieces

The Ultimate California Guide to Tide Pools and Coastal Marine Life

Explore California on Foot: Nature’s Year-Round Playground

Mardi Gras 9 Ways: Parades, Cajun Music, And Courirs Across Louisiana

The Explorer’s Guide to Winter in Germany

Ancient California: A Journey Through Time and Prehistoric Places

The Wildest West: Explore California’s Ghost Towns and Gold Fever Legacy

Sweet California: A Culinary Guide to Tasty Treats Across the State

Sea of Wonders: An Itinerary Through California’s Stunning Shoreline

10 Places to Taste Catalonia’s Gastronomic Treasures

Atlas Obscura’s Guide to Palm Springs

Atlas Obscura’s Guide to the 10 Most Mystifying Places in Illinois

10 Fascinating Sites That Bring Idaho History to Life

North Carolina's Paranormal Places, Scary Stories, & Local Haunts

Exploring Missouri’s Legends: Unveiling the Stories Behind the State’s Iconic Figures

These Restaurants Are Dishing Out Alabama’s Most Distinctive Food

A Gastro Obscura Guide to Los Cabos

9 Watery Wonders on Florida’s Gulf Coast

Discover the Surprising and Hidden History of Monterey County

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Eating Your Way Through Charlotte

Talimena Scenic Byway: 6 Essential Stops for Your Arkansas Road Trip

9 Amazing Arkansas Adventures Along the Scenic 7 Byway

The Explorer's Guide to Highway 36: The Way of American Genius

A Behind-the-Scenes Guide to DC’s Art and Music

9 Places Near Las Vegas For a Different Kind of Tailgate

10 Places to See Amazing Art on Florida's Gulf Coast

8 Reasons Why You Should Visit the Bradenton Area

A Music Lover’s Guide to New Orleans

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Sipping Wine in Catalonia

9 Hidden Wonders in the Heart of Kansas City

10 Unexpected Delights of Vermont's Arts and Culture Scene

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Eating Through Maine

The Gastro Obscura Guide to Asheville Area Eats

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to St. Pete/Clearwater

9 Hidden Wonders in Eastern Colorado

7 Places to Experience Big Wonder in Texas

8 Out-There Art Destinations in Texas

6 Ways To See Texas Below the Surface

9 Places to Dive Into Fresh Texas Waters

7 Ways to Explore Music (and History) in Texas

8 Ways to Discover Texas’ Rich History

The Explorer’s Guide to the Northern Territory, Australia

The Explorer's Guide to U Street Corridor

Gastro Obscura Guide to Southern Eats

Only In Delaware

The Secret History & Hidden Wonders of Charlotte, North Carolina

Exploring Colorado's Historic Hot Springs Loop

These 8 Arizona Ghost Towns Will Transport You to the Wild West

A Guide to Arizona’s Most Striking Natural Wonders

The Explorer's Guide to Hudson Valley, New York

Discover the Endless Beauty of the Pine Tree State

Travel to New Heights Around the Pine Tree State

8 Historical Must-Sees in Granbury, Texas

7 Creative Ways to Take in San Antonio’s Culture

Eat Across the Blue Ridge Parkway

6 Ways to Absorb Addison, Texas’ Arts and Culture

6 Ways to Take in the History of Mesquite, Texas

6 Ways to Soak Up Plano’s Art and Culture

9 Dallas Spots for Unique Art and Culture

7 Sites of Small-Town History in Waxahachie, Texas

6 Natural Wonders to Discover in Austin, Texas

Discover the Secrets of Colorado’s Mountains and Valleys

A Road Trip Into Colorado’s Prehistoric Past

A Feminist Road Trip Across the U.S.

All Points South

Asheville: Off the Beaten Path

Restless Spirits of Louisiana

Eat Across Route 66

18 Mini Golf Courses You Should Go Out of Your Way to Play

4 Underwater Wonders of Florida

6 Spots Where the World Comes to Delaware

Study Guide: Road Trip from Knoxville to Nashville

6 Wondrous Places to Get Tipsy in Missouri

Rogue Routes: The Road to Pikes Peak

Rogue Routes: The Road to Carhenge

4 Pop-Culture Marvels in Iowa

7 Stone Spectacles in Georgia

6 Stone-Cold Stunners in Idaho

8 Historic Spots to Stop Along Mississippi's Most Famous River

5 Incredible Trees You Can Find Only in Indiana

5 Famous and Delightfully Obscure Folks Buried in Kentucky

4 Wacky Wooden Buildings in Wyoming

7 Spots to Explore New Jersey’s Horrors, Hauntings, and Hoaxes

4 Out-There Exhibits Found Only in Nebraska

6 Sweet and Savory Snacks Concocted in Utah

12 Places in Massachusetts Where Literature Comes to Life

8 Places to Get Musical in Minnesota

8 Buildings That Prove Oklahoma's an Eclectic Art Paradise

9 Stunning Scientific Sites in Illinois

5 Strange and Satanic Spots in New Hampshire

8 Historic Military Relics in Maryland

5 of Colorado's Least-Natural Wonders

Rogue Routes: The Road to Sky’s the Limit

6 Hallowed Grounds in South Carolina

9 Rocking Places in Vermont

Knoxville Study Guide

Nashville Study Guide

Rogue Routes: The Road to Camp Colton

Black Apples and 6 Other Southern Specialties Thriving in Arkansas

4 Monuments to Alabama’s Beloved Animals

The Dark History of West Virginia in 9 Sites

11 Zany Collections That Prove Wisconsin's Quirkiness

7 Inexplicably Huge Animals in South Dakota

6 Fascinating Medical Marvels in Pennsylvania

8 Places in Virginia That Aren’t What They Seem

7 Cool, Creepy, and Unusual Graves Found in North Carolina

7 of Montana's Spellbinding Stone Structures

9 of Oregon’s Most Fascinating Holes and Hollows

Take to the Skies With These 9 Gravity-Defying Sites in Ohio

9 Strange and Surreal Spots in Washington State

8 Watery Wonders in Hawaiʻi, Without Setting Foot in the Ocean

6 Unusual Eats Curiously Cooked Up in Connecticut

11 Close Encounters With Aliens and Explosions in New Mexico

10 Places to Trip Way Out in Kansas

The Resilience of New York in 10 Remarkable Sites

7 Very Tall Things in Very Flat North Dakota

8 Blissfully Shady Spots to Escape the Arizona Sun

On the Run: NYC

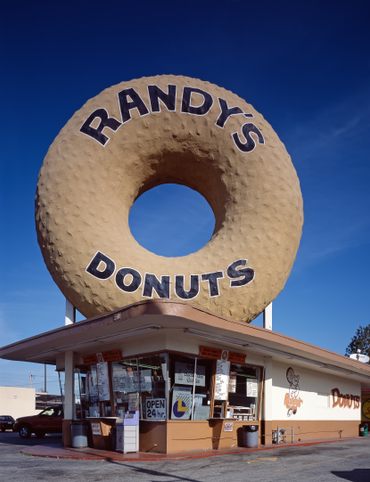

On the Run: Los Angeles

9 Surprisingly Ancient Marvels in Modern California

10 Art Installations That Prove Everything's Bigger in Texas

6 Huge Things in Tiny Rhode Island

7 Underground Thrills Only Found in Tennessee

Sink Into 7 of Louisiana's Swampiest Secrets

7 Mechanical Marvels in Michigan

11 Wholesome Spots in Nevada

7 Places to Glimpse Maine's Rich Railroad History

11 Places Where Alaska Bursts Into Color

9 Places in D.C. That You're Probably Never Allowed to Go

2 Perfect Days in Pensacola

Rogue Routes: The Road to the Ice Castles

Taste of Tucson

North Iceland’s Untamed Coast

Hidden Edinburgh

Hidden Haight-Ashbury

The Many Flavors of NYC’s Five Boroughs

Hidden French Quarter

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Motown to Music City Road Trip

Gulf Coast Road Trip

Hidden Coachella Valley

Highland Park

Venice

L.A.’s Downtown Arts District

Secrets of NYC’s Five Boroughs

Mexico City's Centro Histórico

Hidden Hollywood

Hidden Times Square

Summer Radio Road-Trip

Amsterdam

Buenos Aires

Chicago

Detroit

Lisbon

Miami

Queens

San Diego