From the birthplace of jazz, blues, and country rock, this tri-state itinerary traces the journey of a distinctly American musical heritage through Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

All Points South

Whatever hand the U.S. had in shaping world music, it had its feet planted firmly in the South. From New Orleans, where a confluence of West Africans laid the groundwork for the musical improvisation we call jazz; to Mississippi, where work-songs birthed the blues before the blues birthed rock ‘n’ roll; to Tennessee, where rock intersected with Appalachian folk songs to create country rock, this distinct artistic heritage was forged uphill, from the humblest of origins. Nonetheless, the musical legacy of unsung field hands, farmers, and blue collar workers coming up from the South would go on to change the world, and in no quiet way.

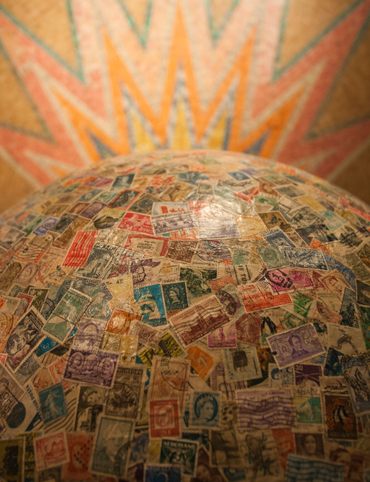

1. Congo Square

In French colonial New Orleans, West Africans were permitted to congregate beyond city limits each Sunday in festivities that typically erupted in songs and dances of their homeland, using recreated instruments and costumes. These gatherings were later relegated to a grassy field that came to be known as Congo Square, a place to which Wynton Marsalis says “the bloodlines of all important modern American music can be traced.”

For over a century, Congo Square reverberated weekly through the recall of drums, gourds, pan-flutes, and a precursor to the banjo, played by both free and enslaved folks from across West Africa as well as the Caribbean. In time, these gatherings drew up to 600 participants at a time, rituals that came to fascinate white townsfolk and visitors alike. This cross-cultural assemblage encouraged a novel form of musical collaboration and improvisation that leads some music historians to see the plaza as the very birthplace of jazz.

Today, Congo Square is framed by enormous oaks, magnolias, and palm trees within Louis Armstrong Park, and it’s still making music: It’s titular fall music festival features African dance, latin jazz, brass bands, and more. The plaza is paved with granite cobblestones that radiate from the center of the Square, as if to mark the exact spot where the outsized seed of African influence on American music was indelibly sown.

701 North Rampart Street, New Orleans, Louisiana, 70116

2. Singing Oak

From Preservation Hall to Palm Court and Mahogany Jazz Hall, Congo Square’s legacy can be heard across the spectrum of historic venues throughout the city. But if you need some outside time, there’s one tree in town that keeps the music going. “Early jazz was invented in New Orleans, it was very improvisational,” said visual artist Jim Hart. “So what could be more improvisational than the wind playing a percussion instrument?”

In Hart’s Singing Oak installation from 2010, dozens of wind chimes from three to fourteen-feet long hang from a century-old oak doling out precisely the five tones that make up the pentatonic scale. While this scale is used across many cultures, this ancient ascension is the foundation of West African gospel hymns, African-American spirituals, and jazz music in particular.

A bench sits below one of the massive boughs, making for a perfect respite from the blaring seasonal Southern heat as well as an ideal spot to take in City Park’s 25 acres of wetland. With a thick canopy, the great oak seems to camouflage the dozens of black-coated chimes harmonizing above and around you. Bathed in sound and enveloped in greenery, the Singing Oak rests at the intersection of New Orleans’ rich musical and natural heritage.

1701 Wisner Boulevard, New Orleans, Louisiana, 70124

3. Dew Drop Social & Benevolent Hall

‘Understated’ is one word to describe this century-old, open-air shack on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain. What its aged wooden frame won’t tell you, however, is that in addition to headquartering an early Black benevolent society, the Dew Drop also once hosted some of the biggest names in New Orleans music during segregation.

Because Mandeville was about 10° degrees cooler than New Orleans at the time, moneyed urbanites of the late 19th and early 20th centuries often ferried north to weekend in cooler climes; Black musicians would hop the ferries as well, playing for tips on the boatdeck before performing in the more formal halls of Mandeville. Unfortunately, during the “Great Redemption”—a period following Reconstruction when gains in civil rights were quietly reversed by Southern politicians—Black musicians weren’t permitted to stay in hotels in Mandeville proper. Luckily, the Dew Drop was three blocks beyond city limits.

While the Dew Drop offered musicians like Buddie Petit, Bunk Johnson, and Louis Armstrong (whose grandmother lived right around the corner) a third act and a place to crash, it was also the headquarters of a benevolent society offering crucial social services to underserved Black families. It was the pride of Black Mandeville, where folks who couldn’t get a loan or healthcare could see intimate shows put on by prominent musicians of the day.

While the Dew Drop was abandoned in the 1980s, it reopened in 2002 to again host southern Louisiana roots music acts. Upcoming events, which run from spring to fall, can be found on their Facebook page. The world’s oldest virtually unaltered jazz hall keeps getting older, but won’t pipe down just yet.

430 Lamarque Street, Mandeville, Louisiana, 70448

4. Teddy’s Juke Joint

Unfortunately, discrimination persisted beyond the Great Redemption. As such, the “Chitlin Circuit” emerged as a word-of-mouth network of Black-friendly performance venues throughout the American South. Teddy’s Juke Joint, ten miles north of Baton Rouge, is one of the last ones standing.

Owner Lloyd “Teddy” Johnson will tell you he’s only ever had one address his whole life. He was born and raised in his eponymous juke joint, back when it was just a shotgun shack at the end of a dirt road. After touring the country as a record DJ, Johnson returned to the thick woods north of Baton Rouge in the 1970s, building a bar and small concert venue onto his childhood home. By the end of the decade, blues acts from around the Delta and beyond were lining up to perform at Teddy’s Juke Joint.

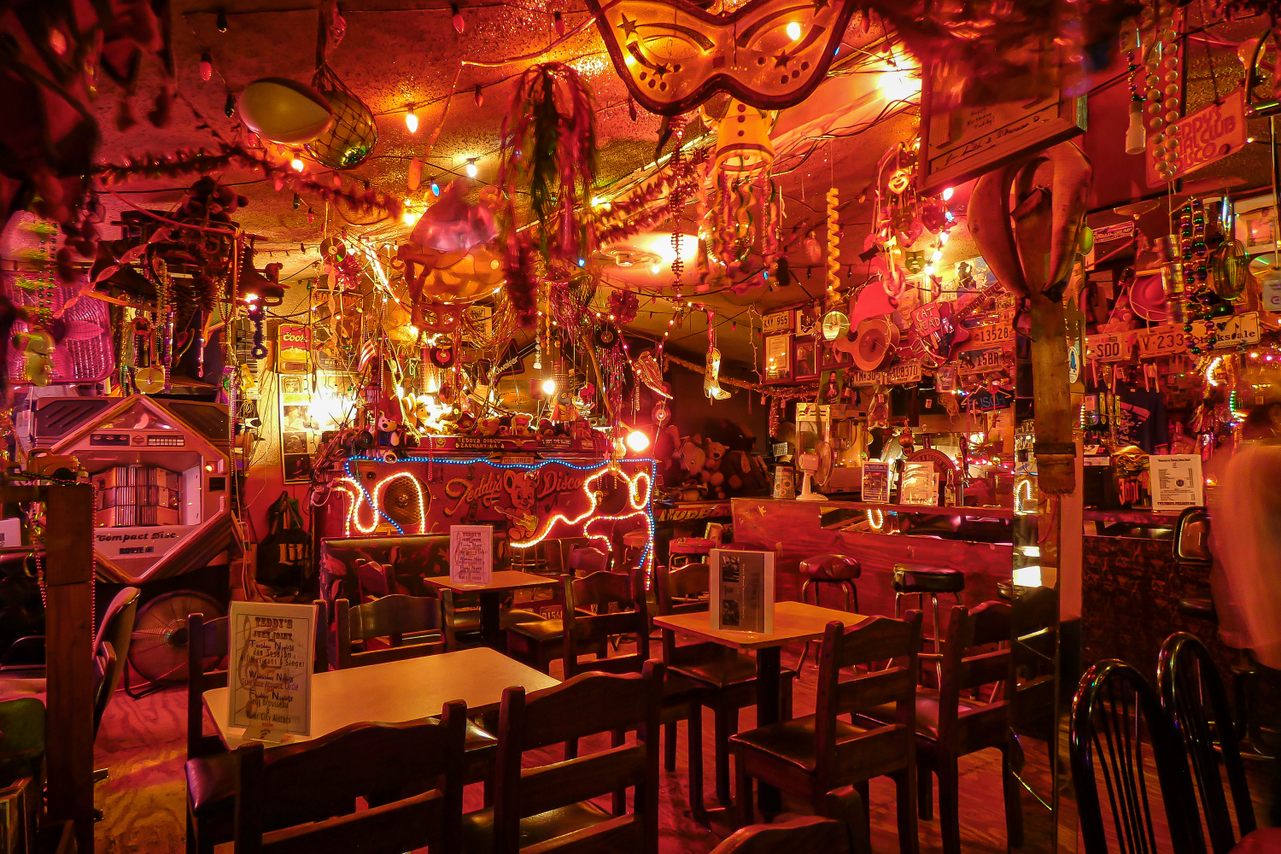

Teddy still books blues acts, though he’s broadened to host rock bands and singer-songwriters as well as an open mic on Wednesdays. One thing he never stopped doing, however, is decorating. Between year-round Christmas lights, disco balls, music paraphernalia, Teddy’s childhood possessions, and a thick canopy of multi-colored tinsel swaying in the air conditioning, one visitor aptly described it as feeling “what I imagine it would be like inside a kaleidoscope.”

While it is a live music venue, the nights without live music are just as much a treat: that’s when Teddy spins. To the backdrop of niche blues, soul, and R&B records, Teddy’s DJ alter ego emerges— flashy, brazen, and raunchy—to crack jokes with bartenders and regulars. Behind a wall of stuffed animals and knick-knacks, summoning stacks of CDs, cassettes, and vinyls, he seems right at home—perhaps, because he is.

16999 Old Scenic Highway, Zachary, Louisiana, 70791

5. Swamp Pop Museum

A former train-depot turned museum in Ville Platte—the “Swamp Pop Capital of the World”—lays out the tale of a little-known genre that, even in its heyday, didn’t have a name for itself.

Southern Louisiana kids born in the 1930s and 40s grew up listening to Cajun, Creole, and country music with their parents. As teenagers during the dawn of rock and roll in the 1950s, they traded fiddles, banjos, and accordions for pianos, horns, and electric guitars. They dropped French to sing in English and adopted stage names northern DJs could pronounce (John Phillip Baptiste becoming “Phil Phillips,” Robert Guidry becoming “Bobby Charles”, etc). Still, the lovelorn lyrics, feel-good rhythms, and harmonized melodies they inherited from their parents shone through, creating a distinct regional sound that—only a decade after its heyday—a British DJ would finally term “Swamp Pop.”

The museum displays artist outfits, instruments, and memorabilia as well as a detailed history of Swamp Pop, with ambient hits playing from a genre you know by sound, if not by name.

205 NW Railroad Avenue Ville Platte, Louisiana, 70586

6. Fred’s Lounge

The opening hours here are no typo: Fred’s is, in fact, only open Saturday mornings from 8 A.M. to 2 P.M. There’s a small chance you’ll be handed a fresh bag of boudin, and an even stronger chance that you’ll be asked to dance.

For 75 years, this windowless brick bar in a 3,000-person prairie town has served as the uncontested “Cajun Music Capital of the World.” Canned beer, well-liquor, and “Fred’s Omelet” (Bloody Mary in a plastic cup) starts flowing around daybreak before a live Cajun band kicks up around 9. By 10, the dance floor is near-to-full and the bounce is in your bones. If you don’t have a dance partner by 11, resident septuagenarian party-starter Rita will come and find you.

Back in the late 1940s, a once-thriving French-American culture had all but faded from the farming communities of Evangeline Parish: French was discouraged in school and Cajun music was giving way to swing jazz and big bands. Alfred “Fred” Tate had had it—the French-speaking Mamou native returned from WWII, opened a big brick bar on Main Street, and reminded Evangeline Parish how Cajun it really was.

Over 75 years strong, the house band at Fred’s only stops so the town councilman—who broadcasts the performance in French on AM and FM stations—can read the names of local sponsors. There’s a host of regulars, but folks travel from every direction each weekend just to party away the morning and keep things French at Fred’s.

420 6th Street, Mamou, Louisiana, 70554

7. Blue Front Cafe

Juke joints emerged throughout the South during emancipation to offer rural Black workers barred from white establishments a place of their own to eat, drink, and enjoy music after a long day’s work. These joints popped up at rural crossroads or by large sharecropping centers—anywhere trafficked by the weary worker. As such, the Blue Front Cafe—nestled between a railroad track and a cotton gin in a small town that once had plantations in every direction—is quintessential “juke,” and the oldest in Mississippi.

Jimmy “Duck” Holmes is the owner and proprietor of Blue Front, a soft-spoken guitar virtuoso and one of the last of the Bentonia bluesmen. If it surprises you to hear he’s a one-time GRAMMY Award® nominee, you’ll believe it when you hear him play. The Bentonia school of blues is distinguished by dexterous finger-picking on drop-tuned, acoustic guitars, set to a hauntingly slow tempo, exuding a deep melancholy—even by blues standards. It’s a niche style making its last stand here at Blue Front, a style sustained by Holmes and several others.

The squat, cinder-block cafe was opened by Holmes’ parents in 1948, intended initially to sell food and beverages to workers from the cotton gin next door. It only became a juke when bluesmen on their way north began giving impromptu performances. When shows became regular, it was made an unofficial stop on the Blues Highway.

During the pandemic, shows have become impromptu once again, a circumstance perhaps more authentic than adverse. If there’s no music when you get there, grab some drinks and hang out. “Duck” may just pick up a guitar and start playing anyway.

107 W Railroad Avenue, Bentonia, Mississippi, 39040

8. B.B. King’s Tour Bus

The trope of the traveling blues musician stems partly from the hopeful pilgrimage many Southern artists often made to Chicago, where audiences craved sounds of the Delta. Like countless others, B.B. King trekked north, but he didn’t stop there.

All told, “The King of the Blues” toured his signature sound in 90+ countries over the course of a 60-year touring career, which was regularly over 200 shows per year. He ran through seven different tour buses doing so, but the longest-traveled one now sits in the B.B. King Museum and Delta Interpretive Center in Indianola, Mississippi.

A special wing of the museum was built to house the black, 42-foot-long 1987 Van Hool Aero Magnum King toured on from 1987–1992. If five years sounds like a short lifetime for a tour bus, that’s because, according to the museum, it drove over 12 million miles—equivalent to 25 round-trips to the moon—bringing King and his band from show to show.

400 Second Street, Indianola, Mississippi, 38751

9. Robert Johnson’s Gravesite

Of course, the impact of blues musicians isn’t always measured in miles traveled or records sold. The elusive Robert Johnson only recorded 29 songs and never formally toured during his life, which was cut tragically short in 1938. Just two pictures of him exist at all. Only posthumously would he become a legendary bluesman.

One of the most famous guitarists of all time died such an enigma that, for nearly a century, no one was even sure where he was buried. His legacy became so iconic, however, his catalogue so canon, that researchers later spent 40 years tracking down his remains to Little Zion Missionary Baptist Church in Greenwood, Mississippi.

The search for Johnson’s grave started in 1965, slowly churning its way through a vague death certificate, contradicting testimonies, and multiple headstones throughout the state claiming to mark Johnson’s remains. Based on corroborating interviews from Johnson’s half-sister, records from the town undertaker, and testimony from the gravedigger’s widow, Johnson’s remains were finally confirmed in 2002 to rest at Little Zion. Now every August—the month of his death—flowers, beers, and notes are left at Johnson’s grave to honor the life of the “King of the Delta Blues Singers.”

For a short life so injected with mythology, it’s refreshing for Johnson’s legacy to retain a semblance of certainty.

Money Road, Greenwood, Mississippi, 38930

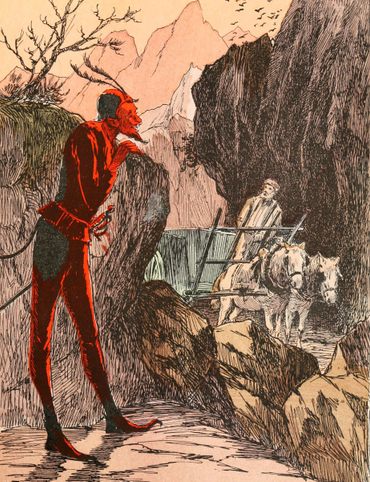

10. Devil’s Crossroads

Indeed, Johnson is the central figure of the darkly romanticized legend of a bluesman selling his soul to the devil for virtuosic guitar skills at the crossroads of Highways 49 and 61 in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

As an upstart musician, the story goes, a young Johnson jumped the stage during intermission one night at a Mississippi juke joint to perform his own songs. The crowd booed him and he was chastised by more accomplished bluesmen. He disappeared that night a nobody and returned six months later an unrivaled master of the six-string. He became so good so quick, they said, it had to be a deal with the devil.

Of course, Johnson mastered his craft the same way anyone else did, though perhaps in a different setting. Blues historians believe he trained under a Hazelhurst, Mississippi, guitarman named Ike Zimmerman, often in the dead of night in the town cemetery where none could hear him. However he did it, his ability to play rhythm, bass, and squealing slides seemingly simultaneously—all while singing, and in a voice aged eerily beyond his 27 years—made him a blues legend, even if he never lived to see it.

Months after he died under mysterious circumstances at age 27, a recording of Johnson’s music was played to a packed audience in New York City’s Carnegie Hall. He received a standing ovation.

North State Street, Clarksdale, Mississippi, 38614

11. Muddy Waters’ Cabin

A lesser-known true tale from Blues history took place in a wooden sharecropper’s cabin now sitting in the Delta Blues Museum. It doesn’t look like much, but the humble shack is so imbued with meaning that it has toured the country with the House of Blues, had several beams removed to make guitars for ZZ Top, and was featured in the opening ceremony of the 1996 Olympic Games.

The cabin once belonged to a man named McKinley Morganfield, a sharecropper living on the sprawling Stovall Farms, just outside Clarksdale. An avid guitarist and harmonicist, he put on shows not only for fellow fieldhands inside the cabin, but for Stovall family functions as well.

Morganfield knew he could play, but it was a 1941 recording of himself, taped in this cabin by Alan Lomax—a renowned ethnomusicologist working for the Library of Congress—that gave him the confidence to journey north. “When he played back the first song I sounded just like anybody’s records,” Morganfield later said. “[I] just played it and played it and said, ‘I can do it, I can do it.’”

In time, Morganfield became Muddy Waters, a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductee, six-time GRAMMY Award® winner, and “King of the Chicago Blues,” responsible for incorporating the electric guitar into a previously all-acoustic genre.

1 Blues Alley, Clarksdale, Mississippi, 38614

12. Elvis Presley's Birthplace

In time, the blues gave birth to rock ‘n’roll—with pioneering artists of each genre continuing to emerge from hardscrabble origins. A two-room shotgun shack in Tupelo marks the spot where a titan of American music made his entrance into the world.

Shortly before Elvis Presley was born in 1935, his parents Gladys and Vernon borrowed $180 to build a small home for the soon-to-be family. While they worked hard on the neighboring dairy farm to pay off their debts, the house was ultimately repossessed before Elvis’ third birthday. “The King” later bought back the home, which sits in its original location but has been redecorated to its late-1930s likeness as the centerpiece of the Elvis Presley Birthplace Museum.

After the eviction, the Presleys stayed in Tupelo long enough to expose Elvis to the building blocks of his imminent musical greatness, which are also on display. The Assembly of God Church, where Elvis first heard Southern gospel music as a child, was relocated in one piece to the museum grounds, and Tupelo Hardware up the street, where his mother Gladys bought him his first guitar, is still open today for customers, Elvis fans, and tourists.

Less is made, however, of Tupelo’s “Shake Rag” neighborhood—an underserved Black community where Elvis first encountered the blues.

306 Elvis Presley Drive, Tupelo, Mississippi, 38804

13. Overton Park Shell

At age 13, Elvis and his folks moved north to Memphis, Tennessee. By age 19, he’d put on his first professional concert, opening for Slim Whitman at this open-air bandshell in Overton Park.

Of the 27 public bandshells built throughout the country in 1936 as part of President Roosevelt’s Depression-era WPA program, the Overton Park Shell (formerly Levitt Shell) is one of only a few still standing. The egg-white, scalloping quarter-dome looks out onto a sloping green lawn framed by oak and pine trees on the east-end of Memphis’ 300+ acre city park.

While it primarily held ticketed operas and orchestras in its early years, the Shell began hosting big bands in the 1940s while making all shows free admission. Later, in the 1950s, directors took a chance on crooners with electric guitars: in fact, the night Elvis Presley stole the show from Slim Whitman in the summer of ‘54 is considered by some to be one of the first rock ‘n’ roll performances in history.

Whatever the case, it was certainly the night Elvis developed a once-controversial trademark move. After missing a cue, he began nervously shaking his legs, sending 5,000 teenagers into a veritable frenzy. “It looked like all hell was going on under those britches,” recalls guitarist Scotty Moore.

While Elvis has left the building, so to speak, the Shell continues hosting both ticketed and free concerts in this rare, historical venue. On any given night during the spring, summer, and fall seasons, visitors can enjoy performances from jazz to rock to symphony, in addition to workshops on health and wellness. Bring your favorite chair or blanket and don’t be late—lawn seating is first come first serve.

1928 Poplar Avenue, Memphis, Tennessee, 38104

14. Memphis Gong Chamber

Between Stax Records, Beale Street, Sun Studio, and Graceland, this city’s musical history runs deep. Nestled within a drum shop in midtown Memphis, however, is an otherworldly sonic experience that brings that heritage to new heights—aural marvels make the dawn of rock ‘n’ roll seem recent.

Gongs have been used for spiritual and ceremonial purposes for well over 1,000 years, and between two windowless rooms in the heart of the Memphis Drum Shop, over 1,000 unique gongs are on display in the Memphis Gong Chamber—and they’re not just for retail purposes.

The shop’s Lesser Chamber offers small and medium-sized gongs for sale, from six inches to several feet wide, but the gongs within the Greater Chamber are not. These behemoth cymbals are here to transport you.

A 7-foot wide Paiste Symphonic gong is the pièce de résistance of Nancy Pettit’s Sound Journeys (private and group appointments bookable through their website). Laying prostrate on zero-gravity chairs in a dimly lit, soundproof room, surrounded by several-hundred pound gongs, listeners are led on a sonic journey through chimes and singing bowls before a mallet-head the size of a melon brings the colossal cymbals lining the walls shimmering to life. They resonate at a frequency so low, it’s less of a sound than a sensation—a transcendent, bronze din that seems to crescendo from within you rather than from any one point in the chamber.

For all the complexities at the intersection of music and human history, it’s refreshing to experience the curation of pure, unadulterated sound—music, in its barest form, as the decoration of time.

878 Cooper St Memphis, Tennessee, 38104

15. Tina Turner Museum

The only museum where one can learn about the origins of Tina Turner is the literal schoolhouse where The Queen of Rock and Roll herself learned to read and write.

Built in 1889, the Flagg Grove Schoolhouse was one of the first schools in the American South made for Black children. Coincidentally, it was her great uncle, Benjamin Flagg, that built it. Like many of her classmates in the 1940s, a young Turner (born Anne Mae Bullock) learned reading, writing, and arithmetic at Flagg Grove before helping her family to pick cotton in the neighboring fields before nightfall.

The building functioned as a school until 1960, when it became a farmhouse that was later abandoned. When Turner found out it was being relocated to Brownsville, Tennessee, in 2012 as part of the West Tennessee Delta Heritage Center, she donated stage outfits, platinum records, private photographs, and her high school yearbook to the exhibit. The schoolhouse now displays Turner’s personal effects as well as the original desks, benches, and chalkboard that first educated the young icon.

121 Sunny Hill Cove, Brownsville, Tennessee, 38012

16. Johnny Cash’s One-Piece-at-a-Time Cadillac

Johnny Cash’s last hit record told the humorous tale of a Detroit auto-worker who stole each individual part of a Cadillac Coupe DeVille, “One Piece at a Time,” over the course of his career. When he finally retired and put it all together, the mismatched pieces made him the laughing stock of town, but he finally had the free Cadillac he’d long dreamed of.

Of course, the song is fictitious, but that didn’t stop Bill Patch, an Oklahoma car collector and Cash-fan, from actually putting together a Frankensteined Cadillac according to the song’s lyrics.

Patch gifted Cash the 1949–1973 DeVille in 1977 and the two went on to become lifelong friends. Just like the song, it’s got mismatched headlights, an asymmetrical tailfin, and patchwork seats and headrests. It’s not just for show either—the one-of-a-kind vehicle actually runs.

The “One Piece at a Time” Cadillac now sits in a garage behind Cash’s long-time rural retreat in Bon Aqua, Tennessee, where he’d unwind after long tours. The car and farmhouse are part of the Storyteller’s Museum, which features rare professional memorabilia and personal belongings that offer a unique window into the private life of the Man in Black. If his nephew Mark is around, he’ll tell you all about “Uncle Johnny.”

9676 Old Highway 46, Bon Aqua, Tennessee, 37025

17. The Caverns

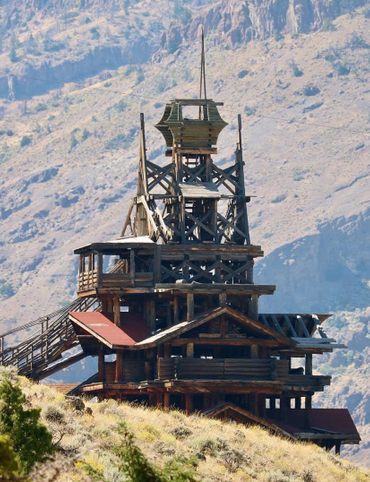

Tennessee has a vibrant musical heritage and over 10,000 caves, so it was inevitable that a couple would become concert venues, but at the end of a dirt road in the Cumberland Plateau, one venture really went above and beyond—or rather, below.

An 18-month excavation process and meticulous vetting by a team of various -ologists transformed Big Mouth Cave into a 1,200-person venue that hosts a range of acts from jam bands to bluegrass and, of course—East Tennessee being its very birthplace—country music. And the cave comes with amenities, too: There’s cold beer on tap, professional sound and lighting systems, enhanced concessions, and bathrooms—although at a steady 59°F year round, you may want to hold onto it. Millions of years in the making, the striking acoustics are all-natural.

The Caverns is home of Bluegrass Underground—a PBS program that brings concerts to the home-screen throughout Tennessee—but it’s also expanding to host EDM, metal, and contemporary Christian shows as well. This living cave and subterranean amphitheater pay homage to the state’s unique musical legacy and geological identity.

555 Charlie Roberts Road, Pelham, Tennessee, 37366

18. Ciderville Music Store

There is no town called Ciderville, and this music shop doesn’t actually sell cider (anymore). It’s a music shop with a down-home venue, an array of bluegrass instruments for sale, and area musicians offering private lessons, but more than anything, Ciderville is an experience.

Owner David West was born on the property, located alongside the Old Dixie Highway, and still lives there to this day. He did inherit a cidery that was once here, but when the drinks business began attracting country musicians who came to play at a now-shuttered concert hall a couple miles up the road, West dropped the cider and picked up the guitar, then the harmonica, and kept collecting until Ciderville became what it is today.

According to West, the “Music Barn” has hosted the likes of Chet Atkins, Bill Carlisle, Kenny Chesney, and other giants of the country and bluegrass world. In the music shop, the few spaces between guitars, banjos, and violins for sale are sealed with faded photographs of southern celebrities, athletes, and musicians who’ve come to visit West over the years. If that weren’t enough already, there’s also a baffling series of handmade folk-art installations on a lawn outside, including but not limited to a staged airplane crash, nine-foot tall rooster named Ro-Ho, and a Noah’s Ark full of ceramic ducks. Ask West ‘why?’ and you’ll only come away with more questions.

2836 Clinton Highway, Powell, Tennessee, 37849

This post is sponsored by Travel South, in partnership with the Louisiana Office of Tourism, Visit Mississippi, and the Tennessee Department of Tourist Development.