A Southern road trip with stops for peanut soup, berry pie, and foraged feasts.

Eat Across the Blue Ridge Parkway

In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt so enjoyed a ride through Virginia’s Skyline Drive that he wanted to make it go on longer—nearly 500 miles longer, to be exact. In the coming months, his administration kicked off a massive roadway project to connect Skyline with Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and the Blue Ridge Parkway was born.

Today, the Parkway remains one of the most beautiful drives in the country, connecting the Great Smoky Mountains to Shenandoah National Park. While its scenic overlooks get all the attention, the region’s restaurants offer a more intimate way to experience the landscape: through the very flavors of the berry bushes that line its trails, the trout that swim in its rivers, and the vegetation that gives its green mountains their striking hue.

From elk burgers at a Native-owned diner to a foraged feast at an Afro-Appalachian restaurant, here’s a guide to the most incredible places to taste the flora and fauna of the Blue Ridge mountains.

1. Paul’s Family Restaurant

Local Cherokee have been hunting and foraging in the area around the Great Smoky Mountains for centuries. Though the United States government forcibly removed them in the 1830s, those who remained or returned have established a community in what is now known as Cherokee, North Carolina.

It’s about a 10-minute drive from Great Smoky Mountains National Park to Cherokee. After a day spent admiring the mountaintop vista of Clingman’s Dome and spotting the elk and black bears that call the park home, visitors can stroll along the main drag of the small town, dotted with Cherokee-themed motels, shops, and cultural institutions like the Museum of the Cherokee Indian.

Those seeking Indigenous fare should stop at Paul’s Family Restaurant. The small house may look like your average roadside greasy-spoon, but the line of cars and motorcycles parked by its porch testify to the Native-owned restaurant’s longstanding appeal. Its Indigenous specialties include bison steaks, pheasant breast, and—for those inspired by the nearby park’s roaming horned beasts—elk burgers.

1111 Tsali Blvd., Cherokee, NC 28719

2. Sunburst Trout Farms

Whenever the weather’s good in Western North Carolina, you’re bound to find folks tubing, kayaking, or fishing in the region’s beautiful rivers. Along with an often-brisk current, the waterways offer an Appalachian specialty: rainbow trout.

Many area restaurants source their trout from Sunburst Trout Farms. The family run business has been breeding trout since 1948. Though the fish are raised in the Shining Rock Wilderness, they’re brought to a small facility in Waynesville (about 13 miles off the Parkway) for processing. This is also the home of Sunburst’s official store, which sells fresh filets, caviar, trout burgers, trout dip, and more. Curious visitors can even take a tour of the facility to learn more about the trout-farming process.

With just a bit of butter, salt, pepper, and garlic, a home-roasted Sunburst filet will rival fine-dining meals that command far higher prices.

314 Industrial Park Dr., Waynesville, NC 28786

3. Benne on Eagle

While farm-to-table restaurants have sprouted up across the United States, few offer diners the chance to forage their own food, then turn it into a dish. On the foraging tours led by Asheville-based company No Taste Like Home, you can collect and eat everything from mulberries to elderflower to birch bark, then drop off some of your finds at one of several local restaurants that will gamely transform them into an appetizer. (You’re free to enjoy the dishes at these restaurant or as takeout, but most require the purchase of an entrée as well.)

One such restaurant is Benne on Eagle, which specializes in “Afro-Appalachian” cuisine, a hybrid of West African, Caribbean, and Southern styles. After I brought my foraged finds of sheep sorrel, day lilies, and plantain weeds, the chef incorporated them into a sweet-and-savory appetizer of Jefferson red rice, plantains, and fermented black beans.

The restaurant’s Afro-Caribbean-Southern menu also includes dishes such as Edna Lewis’ fried green tomatoes; catfish with broken-rice grits; and fufu gnudi with cassava chips, pickled okra, and a maafe (peanut soup) sauce.

35 Eagle St., Asheville, NC 28801

4. Hotel Roanoke

Virginia’s reputation as a peanut-producing powerhouse owes a great debt to the innovations of George Washington Carver and the enslaved chefs who brought West African peanut-based recipes to North America. One such recipe was maafe, a soup from Senegal and Gambia (the very same maafe used in Benne on Eagle’s gnudi).

Though not quite as spicy as maafe, the Virginian version of this peanut soup is a creamy, savory treat. And there’s no better place to sample it than the dining room at the Hotel Roanoke, a towering Tudor-style structure dating back to 1882. The man responsible for the hotel’s recipe is Fred Brown, a legendary Black chef who led Roanoke’s kitchen and debuted his soup in 1940.

Though many restaurants offer versions, Brown’s soup still remains the one to beat. Be sure to order yours with a side of spoonbread—a small skillet of cornmeal-based bread so warm and soft that you can eat it with a spoon.

110 Shenandoah Ave. NE, Roanoke, VA 24016

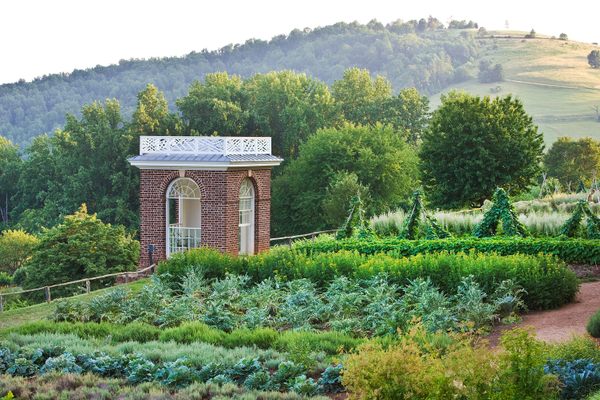

5. Farm Table at Monticello

A little under 30 minutes off the Parkway, Monticello’s splendor is worth the detour. Its vegetable and fruit gardens are particularly spectacular, growing more than 330 varieties of heirloom vegetables and 170 varieties of fruit.

The gardens recreate the botanical collection that Thomas Jefferson assembled from 1770 to 1826. After exploring the sprawling gardens and learning about the legacy of Monticello’s enslaved farmers and chefs (including the exceptionally talented and underappreciated James Hemings), visitors can stop at the site’s Farm Table cafe to sample meals that incorporate the gardens’ offerings.

The cafe’s menu is seasonal and currently offers salads, grain bowls, sandwiches, and soups that incorporate such crops as cucumbers, arugula, basil, peppers, tomatoes, and garlic from the gardens.

Wash down your meal with some Monticello Root Beer or, for those seeking something stronger, a Monticello Mountain Ale (brewed in collaboration with Blue Mountain Brewery). The latter is made with honey from Monticello’s beehives.

931 Thomas Jefferson Pkwy., Charlottesville, VA 22902

6. Shenandoah National Park

In mid-summer, black jewels dangle from the bushes and jammy smudges dot the trails of Shenandoah National Park. During peak blackberry season, visitors can pluck fresh, tart treats as they hike (the National Park Service allows individuals to forage up to one quart per day).

While its natural form is delicious, the local berry’s most decadent manifestation is Shenandoah’s signature Blackberry Ice Cream Pie. A single slice consists of a giant slab of light-purple blackberry ice cream sitting atop a graham-cracker crust and topped with a dollop of meringue and blackberry compote. The result is a sweet, tart, and creamy dessert.

While fresh blackberries are limited to their brief summer window, the pie is available at the park’s two on-site lodges—Big Meadows and Skyland—year-round.

2, Mile 51, Skyline Dr., Stanley, VA 22851

Chattanooga Bucket List Bites

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in New Orleans

Gastro Obscura’s 11 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Bangkok

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Rome

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Around the Great Lakes

10 National Parks That Are Perfect for a Road Trip

11 Out-of-This-World Places You Can Reach in Your Car

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Around Appalachia

The Explorer’s Guide to Road Tripping Down Highway 61

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Stops on an Alternative London Pub Crawl

The Explorer’s Guide to Joshua Tree National Park

The Explorer’s Guide to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Cosmic Colorado: A Stargazer’s Guide to the Centennial State

The Explorer’s Guide to Banff National Park

10 Wild Places That Define West Virginia’s Landscape

The Ultimate Guide to Hidden Red Rocks: 10 Secret Passageways, Artifacts, and Ghost Stories

The Explorer’s Guide to Williamsburg, Virginia

The Explorer’s Guide to the British Virgin Islands

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat, Drink, and Shop in Hong Kong

A Denver Guide for National Park Lovers

Gastro Obscura’s 10 Essential Places to Eat and Drink in Oaxaca

A Gastro Obscura Guide to Family-Friendly Dining in San Diego

The Explorer’s Guide to Outdoor Wonders In Maryland

The Secret Lives of Cities: Ljubljana

From Cigar Boom to Culinary Gem: 10 Essential Spots in Ybor City

The Explorer’s Guide to Wyoming’s Captivating History

A Nature Lover’s Guide to Sarasota: 9 Wild & Tranquil Spots

California’s Unbelievable Landscapes: A Guide to Nature’s Masterpieces

The Ultimate California Guide to Tide Pools and Coastal Marine Life

Explore California on Foot: Nature’s Year-Round Playground

Mardi Gras 9 Ways: Parades, Cajun Music, And Courirs Across Louisiana

The Explorer’s Guide to Winter in Germany

Ancient California: A Journey Through Time and Prehistoric Places

The Wildest West: Explore California’s Ghost Towns and Gold Fever Legacy

Sweet California: A Culinary Guide to Tasty Treats Across the State

Sea of Wonders: An Itinerary Through California’s Stunning Shoreline

10 Places to Taste Catalonia’s Gastronomic Treasures

Atlas Obscura’s Guide to Palm Springs

Atlas Obscura’s Guide to the 10 Most Mystifying Places in Illinois

10 Fascinating Sites That Bring Idaho History to Life

North Carolina's Paranormal Places, Scary Stories, & Local Haunts

Exploring Missouri’s Legends: Unveiling the Stories Behind the State’s Iconic Figures

These Restaurants Are Dishing Out Alabama’s Most Distinctive Food

A Gastro Obscura Guide to Los Cabos

9 Watery Wonders on Florida’s Gulf Coast

Discover the Surprising and Hidden History of Monterey County

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Eating Your Way Through Charlotte

9 Amazing Arkansas Adventures Along the Scenic 7 Byway

Talimena Scenic Byway: 6 Essential Stops for Your Arkansas Road Trip

The Explorer's Guide to Highway 36: The Way of American Genius

A Behind-the-Scenes Guide to DC’s Art and Music

9 Places Near Las Vegas For a Different Kind of Tailgate

10 Places to See Amazing Art on Florida's Gulf Coast

8 Reasons Why You Should Visit the Bradenton Area

A Music Lover’s Guide to New Orleans

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Sipping Wine in Catalonia

9 Hidden Wonders in the Heart of Kansas City

10 Unexpected Delights of Vermont's Arts and Culture Scene

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to Eating Through Maine

The Gastro Obscura Guide to Asheville Area Eats

Gastro Obscura’s Guide to St. Pete/Clearwater

9 Hidden Wonders in Eastern Colorado

7 Places to Experience Big Wonder in Texas

8 Out-There Art Destinations in Texas

6 Ways To See Texas Below the Surface

9 Places to Dive Into Fresh Texas Waters

7 Ways to Explore Music (and History) in Texas

8 Ways to Discover Texas’ Rich History

The Explorer’s Guide to the Northern Territory, Australia

The Explorer's Guide to U Street Corridor

Gastro Obscura Guide to Southern Eats

Only In Delaware

The Secret History & Hidden Wonders of Charlotte, North Carolina

Exploring Colorado's Historic Hot Springs Loop

These 8 Arizona Ghost Towns Will Transport You to the Wild West

A Guide to Arizona’s Most Striking Natural Wonders

The Explorer's Guide to Hudson Valley, New York

Discover the Endless Beauty of the Pine Tree State

Travel to New Heights Around the Pine Tree State

8 Historical Must-Sees in Granbury, Texas

7 Creative Ways to Take in San Antonio’s Culture

6 Ways to Absorb Addison, Texas’ Arts and Culture

6 Ways to Take in the History of Mesquite, Texas

6 Ways to Soak Up Plano’s Art and Culture

9 Dallas Spots for Unique Art and Culture

7 Sites of Small-Town History in Waxahachie, Texas

6 Natural Wonders to Discover in Austin, Texas

Discover the Secrets of Colorado’s Mountains and Valleys

A Road Trip Into Colorado’s Prehistoric Past

A Feminist Road Trip Across the U.S.

All Points South

Asheville: Off the Beaten Path

Restless Spirits of Louisiana

Eat Across Route 66

18 Mini Golf Courses You Should Go Out of Your Way to Play

4 Underwater Wonders of Florida

6 Spots Where the World Comes to Delaware

Study Guide: Road Trip from Knoxville to Nashville

Rogue Routes: The Road to Pikes Peak

6 Wondrous Places to Get Tipsy in Missouri

Rogue Routes: The Road to Carhenge

4 Pop-Culture Marvels in Iowa

7 Stone Spectacles in Georgia

6 Stone-Cold Stunners in Idaho

8 Historic Spots to Stop Along Mississippi's Most Famous River

5 Incredible Trees You Can Find Only in Indiana

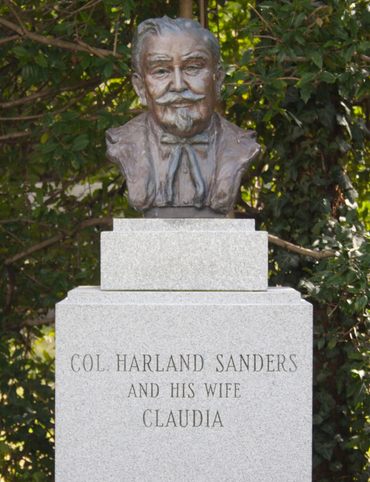

5 Famous and Delightfully Obscure Folks Buried in Kentucky

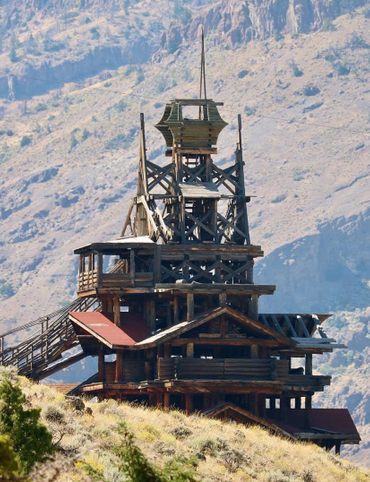

4 Wacky Wooden Buildings in Wyoming

7 Spots to Explore New Jersey’s Horrors, Hauntings, and Hoaxes

4 Out-There Exhibits Found Only in Nebraska

6 Sweet and Savory Snacks Concocted in Utah

12 Places in Massachusetts Where Literature Comes to Life

8 Places to Get Musical in Minnesota

8 Buildings That Prove Oklahoma's an Eclectic Art Paradise

9 Stunning Scientific Sites in Illinois

5 Strange and Satanic Spots in New Hampshire

8 Historic Military Relics in Maryland

5 of Colorado's Least-Natural Wonders

Rogue Routes: The Road to Sky’s the Limit

6 Hallowed Grounds in South Carolina

9 Rocking Places in Vermont

Knoxville Study Guide

Nashville Study Guide

Rogue Routes: The Road to Camp Colton

Black Apples and 6 Other Southern Specialties Thriving in Arkansas

4 Monuments to Alabama’s Beloved Animals

The Dark History of West Virginia in 9 Sites

11 Zany Collections That Prove Wisconsin's Quirkiness

7 Inexplicably Huge Animals in South Dakota

6 Fascinating Medical Marvels in Pennsylvania

8 Places in Virginia That Aren’t What They Seem

7 Cool, Creepy, and Unusual Graves Found in North Carolina

7 of Montana's Spellbinding Stone Structures

9 of Oregon’s Most Fascinating Holes and Hollows

Take to the Skies With These 9 Gravity-Defying Sites in Ohio

9 Strange and Surreal Spots in Washington State

8 Watery Wonders in Hawaiʻi, Without Setting Foot in the Ocean

6 Unusual Eats Curiously Cooked Up in Connecticut

11 Close Encounters With Aliens and Explosions in New Mexico

10 Places to Trip Way Out in Kansas

The Resilience of New York in 10 Remarkable Sites

7 Very Tall Things in Very Flat North Dakota

8 Blissfully Shady Spots to Escape the Arizona Sun

On the Run: Los Angeles

On the Run: NYC

9 Surprisingly Ancient Marvels in Modern California

10 Art Installations That Prove Everything's Bigger in Texas

6 Huge Things in Tiny Rhode Island

7 Underground Thrills Only Found in Tennessee

Sink Into 7 of Louisiana's Swampiest Secrets

7 Mechanical Marvels in Michigan

11 Wholesome Spots in Nevada

7 Places to Glimpse Maine's Rich Railroad History

11 Places Where Alaska Bursts Into Color

9 Places in D.C. That You're Probably Never Allowed to Go

2 Perfect Days in Pensacola

Rogue Routes: The Road to the Ice Castles

Taste of Tucson

North Iceland’s Untamed Coast

Hidden Edinburgh

Hidden Haight-Ashbury

The Many Flavors of NYC’s Five Boroughs

Hidden French Quarter

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Motown to Music City Road Trip

Gulf Coast Road Trip

Hidden Coachella Valley

Highland Park

Venice

L.A.’s Downtown Arts District

Hidden Trafalgar Square

Secrets of NYC’s Five Boroughs

Mexico City's Centro Histórico

Hidden Hollywood

Hidden Times Square

Summer Radio Road-Trip

Amsterdam

Buenos Aires

Chicago

Detroit

Lisbon

Miami

Queens

San Diego