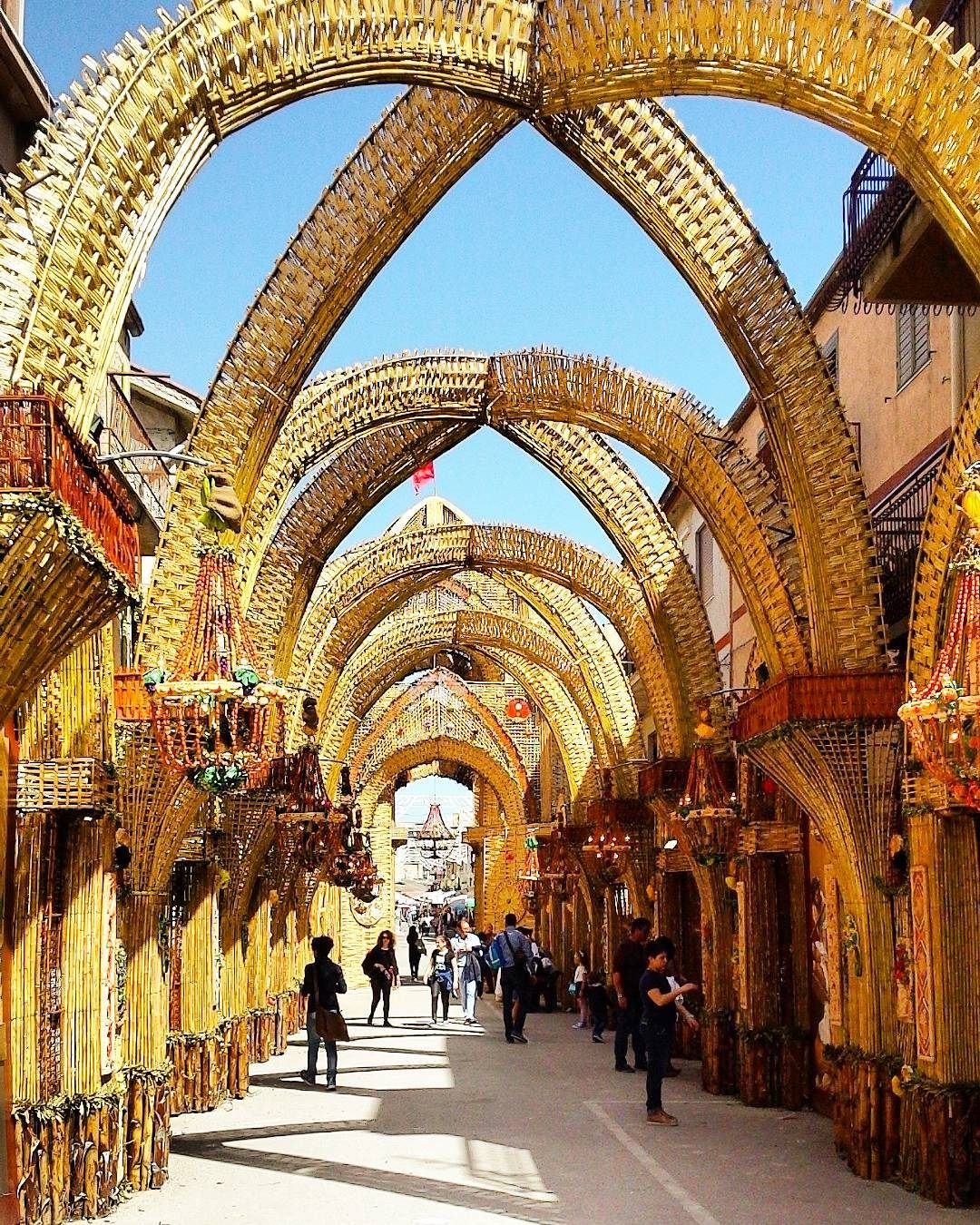

Every Easter, a Sicilian Town Builds a Cathedral Out of Bread

It’s a competitive team sport.

For a month each year, residents of San Biagio team up to build life-size structures made of local herbs, cereals, and bread. This monumental display is both centuries old and one of Italy’s most fantastical traditions: the Arches of Bread.

The festival’s origins trace back to the establishment of San Biagio Platani, a village in southwest Sicily, in feudal times. In the 17th century, Sicily was ruled by Philip IV of Spain, who incentivised the establishment of rural fiefs to meet the Spanish Empire’s growing demand for wheat. In 1635, local landowner Giovanni Battista Berardi bought a farming licence and charter for the pricey sum of 200 ounces and founded a new village called “Lands of San Biagio.”

Carmelo Navarra, a native San Biagese and artistic director of the Arches of Bread Festival, says that it was custom throughout the empire to welcome visiting authorities by constructing sumptuously decorated arches of triumph, such as the Baroque-style “Porta Nuova” in Palermo. But San Biagio was not Palermo. It was a rural town in the Sicilian hinterland. “What could a village of farmers offer to a visiting ruler?” says Navarra. “We lacked marble or tapestries, so we made arches of bread instead.”

Around the mid-18th century, when new rulers no longer demanded ornate displays of welcome, the people of San Biagio adapted the concept for a religious context. “During Easter, the ruler is Jesus Christ, who defeats death and comes back to meet the Madonna,” Navarra explains. As attested by a document kept in San Biagio’s main church, the Church declared that a portion of the village harvest should be used to make the “Arches of Bread.”

Every Easter since, residents have teamed up to build towering structures made entirely of locally sourced, organic ingredients. Men, women, and children build the arches with inlaid sugarcanes, willow, wild fennel, and asparagus under the supervision of local artisans. On Good Friday, they decorate the arches with rosemary, which symbolizes grief. And on the night before Easter Sunday, they replace the rosemary twigs with round-shaped bread loaves, chandeliers decorated with dates, mosaics of made of rice and legumes, and marmurata, a sweet, unleavened bread glazed with white icing.

Each ingredient takes on a symbolic meaning stemming from Christianity and local farming culture. “Bread symbolises farmers’ hard work,” says Navarra, “but it’s also the symbol of the body of Christ.” Decorations reflect this dual symbolism too: Motifs from local folk traditions—such as the sun, moon, and stars—appear alongside Christian icons such as white doves.

Initially, townspeople built just a few arches. But as the tradition evolved, more and more structures were added. “Eventually there were arches on both sides of the original arches,” Navarra say. “So in a way, it resembled the inside of San Biagio’s cathedral, which is made of three naves.”

That’s when things got more fun. Participants started to intentionally position the arches in a way that resembled the inside of the cathedral: a central aisle surrounded by two lateral naves, one leading to the altar of the Virgin Mary, and another leading to the altar of Jesus Christ. Historically, the altar of Mary was curated by the confraternity of Madunnara while Jesus’s was curated by the Signurara. The entire population of San Biagio belongs to one of the two “teams.”

“We decided to play a game,” Navarra says. “Each confraternity would prepare arches for their respective side of the church, and then we would pick a winner.”

A few months before Easter, each team nominates an artistic director whose job is to create an impressive food design. Secrecy is essential, so the planning and building takes place in abandoned warehouses that become food-sculpting labs. Away from prying eyes, each team makes chandeliers from dates, mosaics from barley, legumes, and pasta, and, of course, a varied assortment of bread loaves. Everything gets coated with a natural resin that make the Arches of Bread festival rainproof.

Everyone from toddlers to nonnes (grandmas) is involved. “Children have a lot of fun,” Navarra says. “They usually start with small tasks like making sourdough or gathering seeds and legumes needed to make mosaics. But one day they will run the show.”

This communal aspect of the festival is what means the most to Navarra, who, together with Giuseppe Savarino, the owner of a popular bar on the main street, has led a local initiative to save the festival from recent financial and political turmoil.

Last year, for the first time since the tradition started, San Biagio cancelled its historic Arches of Bread festival due to lack of funds. The town had asked the regional government, which typically provided funding, for an estimated €100,000 that never materialized. While last January, the mayor of San Biagio stepped down after being accused of Mafia ties, which jeopardized this year’s event.

“Skipping the event for two years in a row would have have been a huge loss, and not just for our economy,” Navarra says. “During the months that lead up to the event, the whole town wakes up to life just like nature wakes up from winter. If you take it away, it’s like being stuck in winter.”

Eventually, things turned out for the best. During a heated social media debate about the future of the festival, Navarra came up with a motto: “We surely won’t let the mafia stop the creativity of our people.” Several days later, residents launched a campaign to crowdsource funding and resources. Cafes and restaurants stepped in to sponsor large sculptures; families turned their homes into labs; and many artisans, including Navarra, agreed to build their creations out of pocket.

This year Navarra is working on an organic bas-relief that represents Peppino Impastato and Father Puglisi (two figures who challenged the Mafia). “What’s great is that everyone did what they could to make it happen,” he says. “We are an isolated community, and our ability to be creative with the products of our land is our greatest asset.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook