How New Orleans Made a Medieval Sicilian Tradition Its Own

St. Joseph protects communities during times of sickness and famine.

In the Middle Ages, the story goes, a great famine ravaged Sicily. Peasants starved. The rain refused to come. In desperation, villagers prayed to Saint Joseph, the Biblical carpenter whom Christians believe to be Jesus Christ’s earthly foster father. If the Saint would intervene on their behalf, the Sicilian people promised, they would honor him with a selection of their harvest from then on.

The rains came, and an abundant harvest of fava beans restored order to the land. Ever since, Sicilians have celebrated St. Joseph’s Day each March. To mark the occasion, communities feast and offer alms to impoverished neighbors in the form of lavish dinners. And they erect elaborate culinary altars, whose ornately symbolic contents, from bread sculptures to pastries, represent the abundance the saint restored to the island.

You can still find St. Joseph’s Day altars in Sicilian churches and piazze. But it’s one of those folk traditions that may actually be more popular in the diaspora. The holiday is particularly visible in the United States, where, every March 19, Sicilian-American communities enjoy traditional St. Joseph’s feasts of pasta con le sarde: bucatini pasta with sardines, fennel, pine nuts, and raisins.

One of the most lively St. Joseph’s celebration is in a seemingly unlikely place: New Orleans, where celebrations blend Sicilian, African American, and other European immigrant traditions. While popular representations of Italian Americans—think The Godfather or The Sopranos—focus on New Jersey, New York City, and Chicago, the city of New Orleans has a significant history of Sicilian and Italian immigration. Despite helping to shape the city’s famous Creole culture, says Justin Nystrom, a Loyola University history professor and author of Creole Italian: Sicilian Immigrants and the Shaping of New Orleans Food Culture, Italian immigrants are often erased from conventional accounts of New Orleans. But Sicilian immigrant influence continues to permeate New Orleans, from more popular cultural icons like the music of Louis Prima and the muffuletta sandwich, to the diaspora’s less well-known, but equally important, role in shaping the region’s citrus trade.

“New Orleans tells the same stories about itself: antebellum,” says Nystrom. “This really big immigrant influence got lost.” Popular New Orleans histories tend to glorify pre-Civil War Days, focusing on what Nystrom calls “hoopskirt” tropes of genteel Southern society. This risks whitewashing the horrors inflicted on African Americans during slavery, and obscuring the influence of immigrants.

St. Joseph’s Day embodies the dynamic role Sicilians played in shaping New Orleans’s creole culture. Celebrations include elements of Italian tradition, African American Mardi Gras culture, and Irish immigrant festivities. For weeks before the feast day, churches, neighborhood associations, and families erect elaborate altars to the saint. Neighbors and relatives visit from door to door, and gather for feasts of pasta con sarde and traditional St. Joseph’s Day zeppole pastries.

At the climax of the holiday, the Italian American St. Joseph’s Day Society, a local cultural organization, sponsors an elaborate community dinner. “It’s 500 pounds of pasta con sarde in a six-foot pasta bowl,” says Mark Fonte, a member of the Society’s board of directors. The dinner is accompanied by a festive French Quarter parade, in which tuxedo-and-evening-dress-clad community members ride through the streets on floats. A massive, mobile St. Joseph’s altar reigns over the parade, and participants toss Mardi Gras beads and fava beans, a symbol of good luck, to onlookers.

These traditions represent the abundance St. Joseph brought to medieval Sicilians. But the history of Sicilian immigration in New Orleans wasn’t always characterized by such largesse. Ever since Arab conquerers brought lemons and citrons to Sicily in the 800s, the island has been a center of the citrus trade. In the mid-1800s, Sicilian citrus merchants migrated to the American Gulf Coast, where they set up shop trading in oranges and lemons. Those relatively wealthy initial migrants became padrones, labor agents, who facilitated the entry of thousands of working-class Sicilians fleeing the poverty and social turmoil of Southern Italy. Many settled in northern urban centers such as New York, and became factory or food-service workers. But others migrated to the American South, where many became waged plantation laborers. Soon, Italians had become pivotal to the region’s food system, as small grocery store owners, restaurant owners, and food distributors. In the 1800s and early 1900s, an estimated 40,000 Sicilian immigrants entered the United States through New Orleans. By 2000, there were 250,000 people of Italian descent living in the New Orleans area.

In Sicily, St. Joseph’s Day is a regional holiday, and its celebration varies by village. But when Sicilians moved to the United States, St. Joseph’s Day came to embody their immigrant identity. “You may have had people who didn’t do St. Joseph’s in Sicily, but when they came to the United States, they fell into the culture of people who did,” Nystrom says. In New Orleans, celebrations to mark the holiday rippled beyond Sicilian communities to incorporate and influence other European and African American traditions unique to New Orleans.

The community’s main sphere of influence: food. By 1900, Sicilians had a substantial presence in New Orleans’s corner grocery stores and eat-in restaurants, and they dominated the local oyster trade. Soon, even New Orleans’s American-born elite had developed a taste for red sauce. “By the 1920s, ladies are going to spaghetti restaurants,” Nystrom says. These restaurants spurred a new, uniquely New Orleanian Sicilian cuisine, which produced Italian-American staples such as the immensely famous muffuletta sandwich and the “Wop Salad.” Named after a slur for Italian-Americans, the salad mixed Sicilian ingredients such as asparagus and anchovies with Worcestershire sauce and Gulf Coast boiled shrimp.

Sicilians’ role in the “hustle” of the restaurant industry brought them into close working relationships with the city’s African American residents, and the emerging genre of New Orleans jazz. “Italians are creolizing themselves because they’re in a hustle,” Nystrom says. Black musicians often played in Italian restaurants, and Italian musicians combined elements of this music with folk tunes from Italy to create a style of zany, often self-deprecating immigrant jazz. The genre is perhaps best embodied in the brassy bravado of Louis Prima. “The Sicilians are kind of like cultural chameleons,” Nystrom says.

However, relationships across racial and ethnic lines were often tense. Sicilians were at the receiving end of anti-immigrant discrimination. In 1891, following the murder of a police officer, a mob of New Orleanians lynched 11 Sicilian men. In 1922, an Alabama judge ruled that a Sicilian immigrant was “inconclusively white,” and therefore her African American husband couldn’t be punished under Jim Crow laws prohibiting miscegenation. Some left-leaning Italian immigrants attempted to forge labor solidarity with African Americans. Many others perpetuated anti-Black racism, and mainstream Italian-American newspapers often used racist tropes to assimilate Italians into the privileges of U.S.-born whiteness. Today, New Orleans’ once-racially mixed neighborhoods are increasingly segregated.

But St. Joseph’s Day continues to reflect the historic diversity of New Orleans. “St. Joseph’s Day also has this syncretic quality about it,” says Nystrom. Even during times of formal segregation, neighbors often visited St. Joseph’s altars across racial lines. “You’d see people of different racial groups come in and eat spaghetti in your home.”

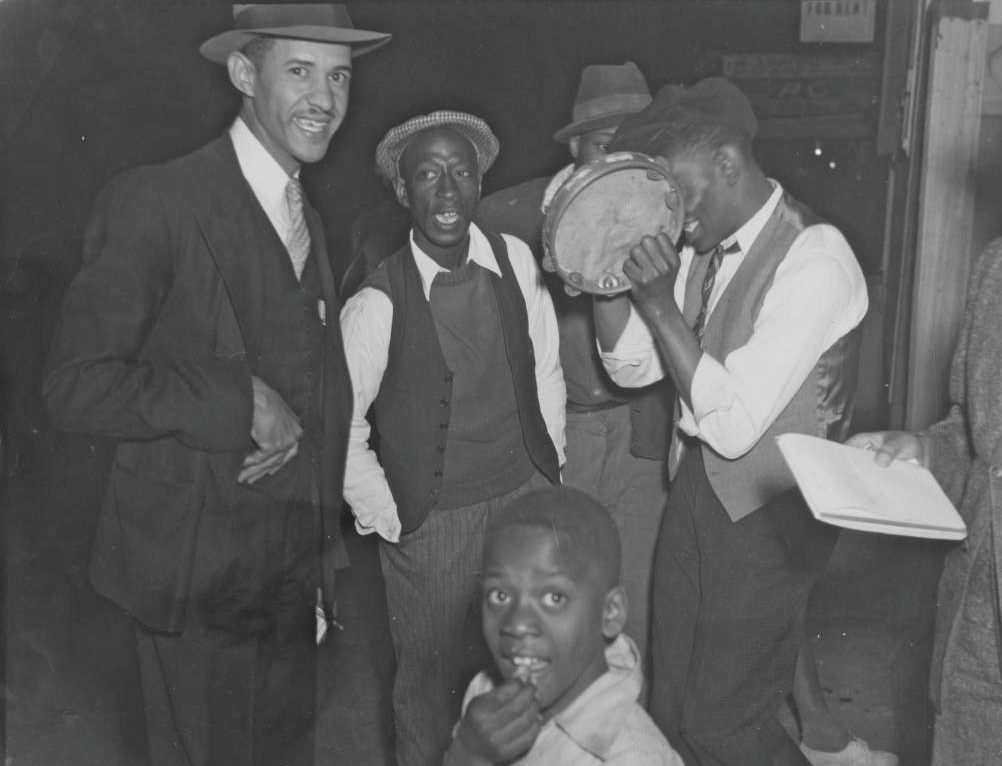

Today, Catholic churches around the city, including historically Black-led and integrated churches such as St. Augustine’s, erect St. Joseph’s Day altars. Several communities of Black New Orleanians who famously don feathery displays during Mardi Gras also parade the weekends before and after St. Joseph’s Day—a tradition that community leader Chief Shaka Zulu dates back to mixed Black and Sicilian neighborhoods. The week after St. Joseph’s Day, Italian and Irish communities celebrate their historical coexistence in the annual Irish-Italian Parade.

For Susan Vacarella, who lives with her family just outside of New Orleans, the holiday is a reminder of the role faith played in sustaining Italian immigrants. “I just can’t say enough about St. Joseph. He’s been very good to our family,” she says. For two decades, Vacarella has spent months preparing food for her family’s altar. Her husband’s ancestors appealed to St. Joseph for help when they first came to the United States. Just like the famine-struck medieval Sicilians, Vacarella erects an altar each year as an expression of thanks.

The tradition began in 1931, when Benedicta Mangano Vacarella, Susan’s husband’s grandmother, needed the Saint’s intercession. Vacarella’s family had left Sicily 20 years earlier to work as waged laborers on a Louisiana plantation. As the Great Depression emptied out American larders and bank accounts, Benedicta’s son fell deathly ill.

So Benedicta made St. Joseph a promise. “If he would intercede for the recovery of her son, then she would start her altar,” says Susan Vacarella. Benedicta’s son recovered, and she later taught Susan Vacarella, who did not grow up in a Sicilian family, how to make her own altar. Now, Vacarella carries on the tradition. For the past 20 years, she’s spent months preparing sweet and savory dishes for the elaborate display. “I usually start right after Christmas,” she says. “By mid-February I have the altar up.”

Each object carries symbolism. Ornate bread sculptures, shaped like crosses, fish, and carpenter’s tools, represent St. Joseph’s woodworking profession. Mountains of confections froth from the white tablecloth, including rainbow-colored, fig-filled cucidati cookies, sugar-syrup-dripping pignolata cookies, and puffy, cream-filled zeppole. Bright oranges and lemons evoke the island’s famous citrus trade. Fava beans, a reminder of the gift that broke the mythical famine, dot the display; Sicilians in New Orleans call them “lucky beans” and hand them out to visitors.

“If you put it in your pocket, or your purse, or your food pantry, you’ll never be without food,” Vacarella says. With over 100 neighbors visiting her altar in the course of a regular season, Vacarella has a lot of luck to give. A statue of the saint, framed by flowers and carrying the infant Jesus, guards the offerings—and, the faithful hope, his devotees.

This March, St. Joseph’s guardianship carries even more weight for the faithful. In contrast to the raucous parades and pasta suppers that usually accompany the feast day, 2020’s festivities will be muted. New Orleans has cancelled all parades, including the St. Joseph’s Day parade, to prevent the further spread of COVID-19, which the World Health Organization has labeled a pandemic. As of March 16, the CDC advised against gatherings of more than 50 people, and President Donald Trump discouraged gatherings of more than 10. With more states mandating lockdowns, Louisiana may soon follow suit. That means even small gatherings to mark the occasion are likely to be called off.

Vacarella has already spent months preparing her altar. The disrupted festivities are disappointing, but she connects them to the holiday’s core story. The current public health crisis evokes the medieval Sicilian famine, and the illness and miraculous recovery that first motivated Benedicta Mangano Vacarella to erect a St. Joseph’s Day altar in thanks.

This year, as she lays her altar, Vacarella hopes that St. Joseph will continue to comfort those who love him. She puts her trust in “Those three f’s: faith, family, and friends,” she says. “Especially in this time.”

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook