How Pearl Meat Became Australia’s Newest Luxury Ingredient

Once humble divers’ fare, the meat of the pearl oyster now commands up to $200 per kilo.

“Give it a good crack, go on. Put some welly into it.” I twist the chock of wood into the oyster and the shell yawns open, revealing a fleshy mass of guts inside. The other members of the farm tour lean forward and coo as I reveal its contents: Hidden within the pulp is a bright, gleaming pearl. They watch as the marine biologist carefully removes it and buffs it clean, but I stare at what remains in my hands. I’m far more interested in this fleshy mess because I know just how valuable pearl meat really is.

It’s easy to see why the mother-of-pearl shell was once so coveted. To look at its iridescent nacre is like gazing into the eye of a swirling, glittering storm. For almost a century, more than 80,000 tons of the Pinctada maxima pearl shell were exported globally from Australia for use in the production of fashionable mother-of-pearl buttons. When the advent of cheaper, easier-to-produce plastic dimmed the appeal of the natural product, commercial focus shifted to the glamorous and lucrative pearls themselves. But now, more than 140 years since the first hard-hat divers walked these coralline sea beds, it’s the comparatively pedestrian offshoot of pearl meat that’s getting people excited.

Pearl meat—specifically the large, ear-shaped adductor muscle of the South Sea oyster—is already sought-after on the market in Hong Kong and Japan, where it can command up to $200 a kilogram. You’ll find it sprinkled throughout the menus of some of Australia’s finest restaurants, too, from Bentley in Sydney, where it’s served doused in salted apple, buttermilk, and yuzu kosho, to Flower Drum in Melbourne, where it’s carefully cubed and plated alongside fresh spring onion and asparagus.

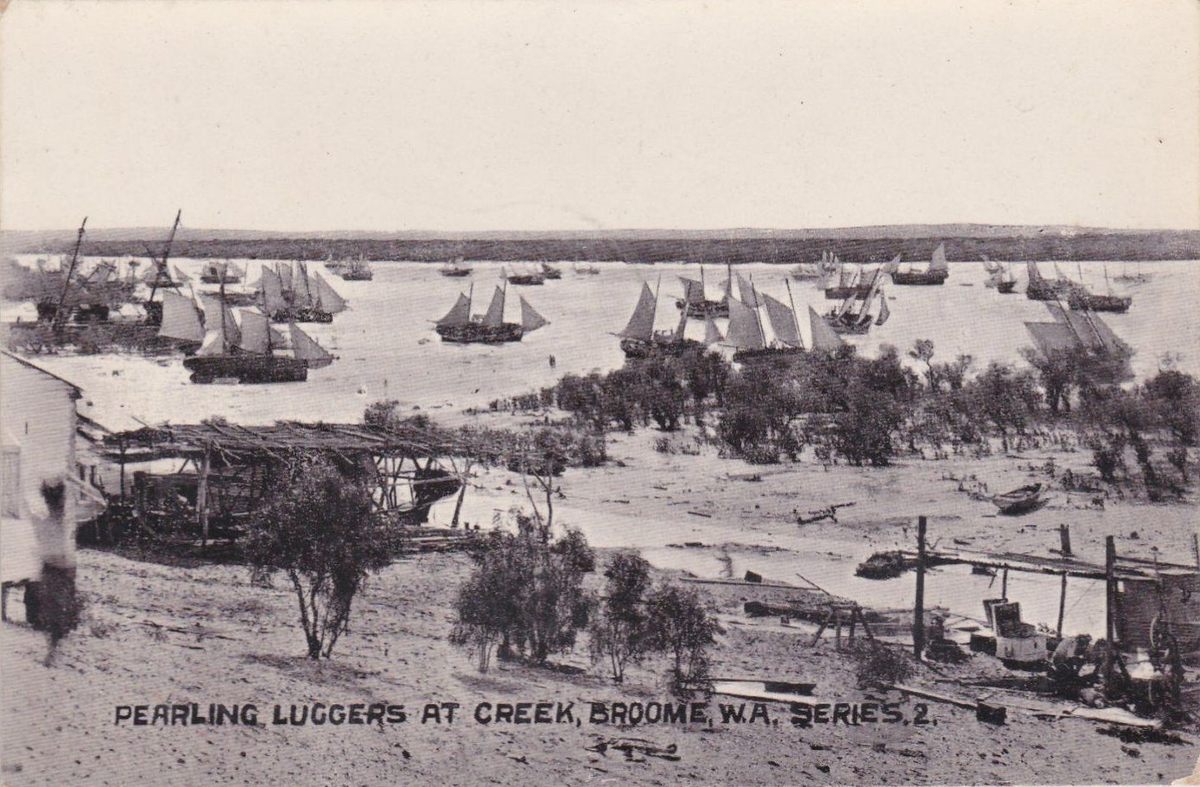

Pearl meat’s roots, however, can be traced back to the tiny coastal township of Broome in north Western Australia. In the mid-1800s, the discovery of rich pearl shell beds off 80 Mile Beach sparked a Gold Rush–style influx of settlers to Broome. Thousands of Japanese, Chinese, Malay, and Filipino divers descended on the tiny, red dust–covered township, along with prospectors from Britain, North America, and Europe, all seeking their fortune in this intriguing but perilous industry. They built jetties and set out in pearling luggers, primed to push their prows into mangroves, creeks, and channels in search of fresh pearl shell beds to plunder. Hotels popped up, serving pannikins of grog to multicultural crews seeking comfort from the rheumatic divers’ aches that plagued their joints.

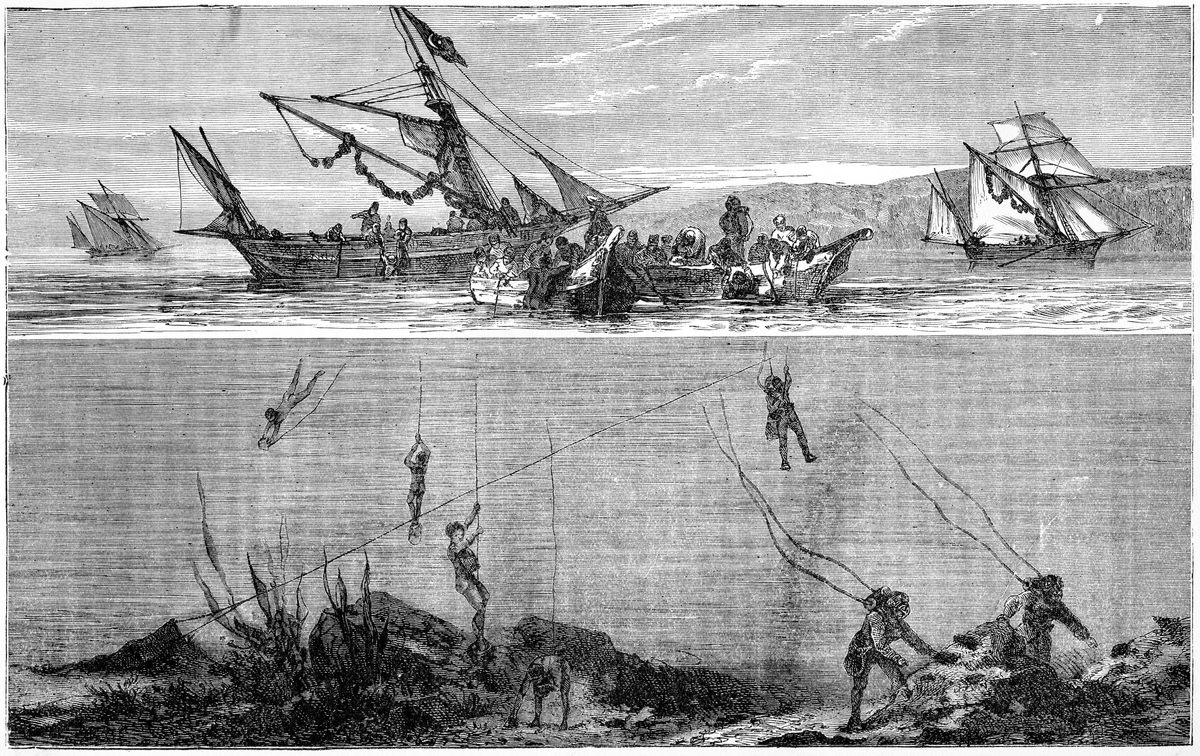

In these early stages, pearling was a dangerous and desperately unregulated industry. The Indigenous population around Broome was cruelly displaced and many men, women, and even children were kidnapped by the early pearlers and forced to dive naked, or in “bare pelt.” As the industry developed, however, and the Pearl Shell Fishery Regulation Act was introduced in 1875, the fabric of the lugger crews shifted. Men from all over the world came to seek work on the luggers; most of them willingly, some for adventure, and usually as a response to the poverty of their home villages.

To supplement their meager wages, they would salvage the meat from the pearl shells they’d hauled in (often nibbled at by cockroaches), dry it from the salty lugger beams, then hawk it to merchants in Broome’s Chinatown. “The pearling camps stank to high heaven,” writes historian Hugh Edwards in his book, Port of Pearls. “The air was putrid with the reek of rotting shellfish, and when someone stirred his pogey tub [the pots in which they boiled the old shell to release any pearls sheltering within] even hardened locals walked delicately to windward.”

So how has pearl meat gone from pungent diver’s fare to an ingredient that commands the sorts of prices usually reserved for white truffle and Wagyu beef? “Chefs are waking up to the possibilities that pearl meat presents,” says pearl farmer and marine biologist James Brown.

Brown runs a pearl farm in Cygnet Bay, a remote town about 200 kilometers (125 miles) north of Broome, and sells the meat wholesale through his company, Pearls of Australia. “It’s an unusual product, unique in flavor profile and texture, and there’s also long-standing intrigue and romanticism that comes with the pearling industry. But most of all, this is a rare ingredient.” Brown points out that Australia produces only a few tons of pearl meat each year. “If a restaurant wanted to use it, they’d be very lucky to be able to get hold of it. People like that. It creates demand.”

The product is rare because producing it—much like prospecting for a pearl—is a lesson in the art of patience. A farmed oyster needs careful nursing from its larval stage to the point at which it is “seeded” (that is, when a small irritant gets planted inside the oyster, causing protective nacre to slowly form around it) and then produces a pearl. That can be as long as seven to 12 years, and only then, when the shell is discarded, can you extract the meat—and even then perhaps only 20 grams of it.

Brown is an impressive businessman (he recently became the first water-based farmer to win Australian Farmer of the Year) and is firmly focused on turning pearl meat into a viable commercial concept. “We’re scaling up. We’re investing,” he says. As well as recent infrastructure upgrades, including the paving of the red dirt track that connects Cygnet Bay with Broome, Brown is funneling money into sustainable farming technologies to allow the farm to increase the number of wild oysters they harvest for seeding. He’s already taken his philosophy down to the Hawkesbury River in New South Wales, where the company successfully farms Pinctada fucata pearl oysters, which produce akoya, a meat much more like a traditional oyster, served whole, fried, or smoked at fine dining joints such as Vasse Felix in Margaret River.

Whichever variety is used, it’s an incredibly versatile foodstuff. When I taste it myself, the meat is tender and surprisingly sweet, somewhere between abalone and scallop. “It’s a fun ingredient to work with,” says Rob Boorman, chef and manager at the Cygnet Bay pearl farm’s on-site restaurant. “It can be flash-fried, braised, made into sashimi or ceviche.” This versatility is showcased at the annual Shinju Matsuri festival of the pearl in Broome, where chefs compete to serve up the best pearl meat fusion dishes. Recent winners have included citrus-marinated pearl meat with chili mud-crab croquette, pineapple salsa, and mango gel.

But while pearl meat is relatively unusual on the restaurant scene, Indigenous communities around the Dampier Peninsula have been eating it for tens of thousands of years. “Aboriginal people foraged for guwan [pearl shell], cooked the meat over the fire, used the shells for plates, as decorative riji, or as tools,” Yawuru guide Bart Pigram tells me as we pick our way through the muddy mangroves around Broome. Pigram’s great-great-great-grandfather was a pearler and “blackbirder,” who kidnapped Aboriginal people to staff his boats and took a Yawuru wife, who bore him children.

Learning about this family history spurred Pigram to learn more about the pearling industry as well as his own ancestry. He tells me that, for Aboriginal people, the pearls themselves would have been seen as useless byproducts, occasionally used in slingshots for birds or simply tossed aside. In fact, one of Australia’s oldest dated pearls, found in a layer of discarded shells in a north Kimberley rock shelter, was likely spat out while someone was chewing their foraged pearl meat 2,000 years ago.

“They might be charging $200 dollars a kilo for it now, but this is something Aboriginal people have been eating, for free, since they got here,” Pigram says of pearl meat. He raises an arm and points to a hill in the distance. I squint to see that it sparkles with shards of white like thousands of sequins. “It’s a sacred site, an old midden,” he explains. “Mob [a family or social group] would forage for shellfish, whelks, crabs and pearl meat, then discard the shells.” I look at the hill. It’s carefully protected from the public but a group of black kites squabble boisterously overhead. “It was like an all-you-can-eat-buffet,” Pigram says, smiling. “No expensive prices, nothing fancy, just food.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook