A Deep Dive Into the Intersection of Art and Science With an Artist-at-Sea

Ale de la Puente collaborates with researchers to explore new ways of understanding our universe.

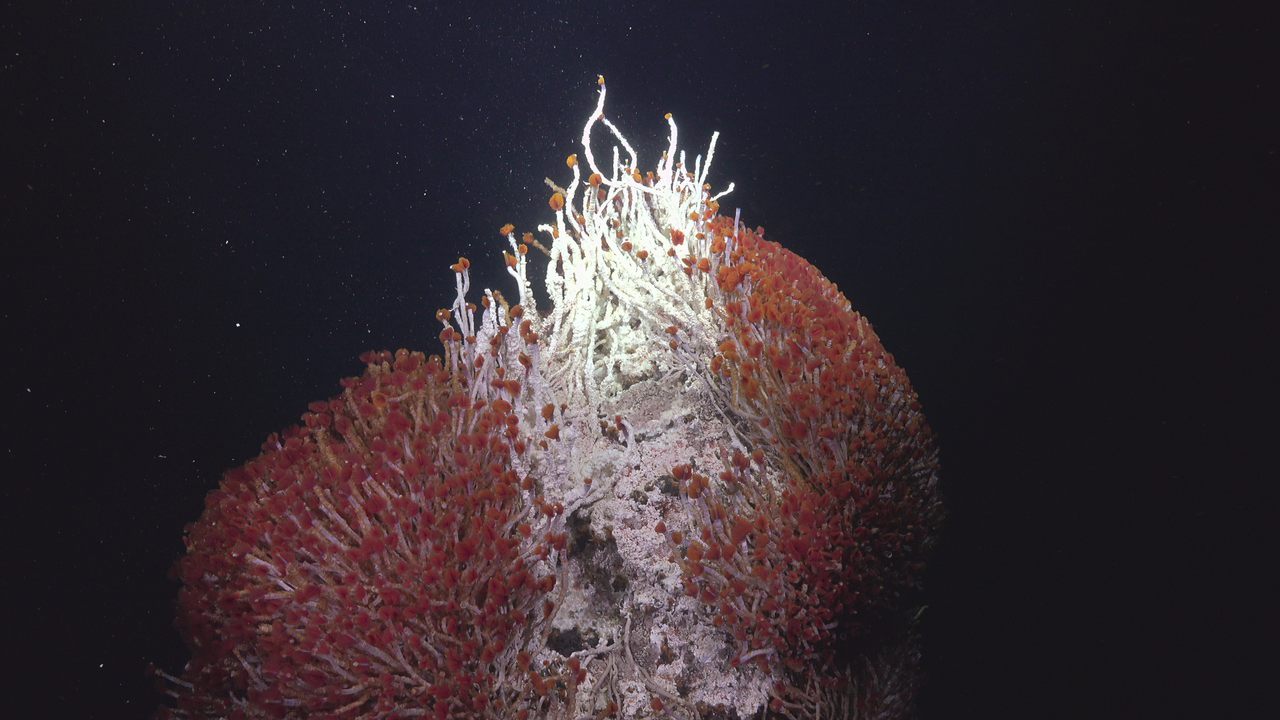

When the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel Falkor headed to the Gulf of California recently, it carried a typically wide-ranging crew. An international, multidisciplinary team of scientists planned to study the deep-sea environment of a depression known as Pescadero Basin, with depths of more than 12,000 feet. The basin’s unique hydrothermal vents—accessed by the team using the underwater ROV SuBastian—form elaborate calcite spires and spew clear fluid, unlike the “black smoker” vents found in the Atlantic and elsewhere.

Life thrives in this extreme environment. The researchers documented iridescent blue worms, mineral-munching anemones, and species that may be new to science. With SuBastian’s help, the team also collected rocks and other samples that may be critical to understanding more about the tectonic plates grinding below our planet’s surface. And watching it all with a keen eye was the expedition’s artist-at-sea, Ale de la Puente.

Having a conceptual artist aboard a research vessel might seem surprising, but de la Puente has been collaborating with scientists for more than a decade. Previous projects have taken the Mexico City native to CERN, in Switzerland, and to Russia’s “Star City” cosmonaut training center.

Atlas Obscura spoke with de la Puente about the recent Falkor expedition, making time dance, and what scientists and artists have in common.

What was your role aboard Falkor?

The role of the artist, for some people, can be a spectator. On a boat, no one is a spectator. I want to see everything and understand not only the research, but how do you work together to make it happen? There were things that were very simple but that took my attention. I loved, for example, when no one is there in the control room, just the pilots taking SuBastian down [to the seafloor]. Yes, I know there are 40 minutes where you’re only going to see the sea but suddenly you see some kind of shape for a moment, and the pilots go “Biology!” This is the most inclusive word. It’s “biology.” It’s not an animal or a plant, just biology.

I was there from SuBastian going down to SuBastian coming up, I wouldn’t even go to eat, someone would bring me something. I felt like I was going to miss something important. Throughout history, we have all the discoveries and we have the data, but we don’t often have documentation of the experience.

What stood out to you about the location in the Gulf of California?

They call it the Gulf of California, but I cannot stop calling it the Mar de Cortés [laughs]. I think “gulf” defines something through the edges of the land. Mar de Cortés is defining the water, the sea itself. It doesn’t need the edges to be defined. It’s called the aquarium of the world, and it’s a very calm sea, a beautiful sea to sail. One of the nights that was the most beautiful, the most calm, the sea was like a mirror. And it was the first time I saw Venus really set on the horizon, and become red, and I saw the reflection of Venus on the sea. I never thought I would see that. It is so far away, but we had the conditions to see it. And I think that, to be able to do the discoveries that they did on Falkor, you have to have the conditions in yourself to see them. It’s something that all the scientists had, patience to keep calm, and to be clear.

What was the most memorable moment of the expedition for you?

The first rock we found. We had a lot of emotions. The first one is like the first kiss [laughs]. SuBastian grabbed a rock, and then when it came up, it’s a two-million-year-old rock and it’s the first time it touched the air. The scientists start touching it, because that’s the dialogue for the geologists, how it feels, to listen with their hands to the story of the rock. But it was like they were taking care of it, like it was just born. We took it to the lab and all of them were touching the rock and feeling it. [I watched how each of us] related with that thing that is not alive, but it’s kind of a biopsy of Earth, of the story of the planet’s cracks and shape, its wrinkles and vents.

You’ve put yourself in some extreme environments in the past, including a weightless parabolic flight out of Star City in Russia. What was that experience like?

My colleague Nahum and I invited other artists to participate, to explore the concept of gravity from the artist’s point of view. To do that, we had to know the concept of gravity, how it works and how we define it today. We asked physicists for a class of the physics of gravity for artists. We were trying to understand what it means, and what the questions about gravity are today—we were going to explore it in zero gravity.

My experiment was with time. The idea of time changes with gravity. We measured time on Earth, in the beginning, before digital clocks, using gravity. I put an hourglass in front of a camera for a fixed shot. When the hourglass was in zero gravity, the time stopped flowing from one side to the other but it didn’t pause. It danced, and swirled around beautifully. Time can stop but it doesn’t freeze.

What draws you to collaborating with scientists?

I love their passion. I think artists and scientists are professions where you are not there because suddenly life puts you there. You have to be stubborn and you have to have a passion and you have to love it, to live it. You’re looking for something to surprise you.

The first work I did with a scientist was actually with a mathematician and a linguist. We were in a cantina, having drinks and talking about math. I said, “I want to know, what is the cubic root of ‘always.’ I have the intuition that it’s minus-1, let’s try to prove it.” The linguist said “Ok, what number would you give to ‘always,’ and is it the same as ‘never’?” We started talking and talking and talking. I loved that. That’s something that keeps drawing me to work with the scientists.

We share the same question, the same search, the same motive, but the science part answers the way it answers and then art finds its answer, showing something else.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook