New Species of Octopus Thrives in Deep Sea Nurseries

At warm, deep sea springs off Costa Rica’s Pacific Coast, throngs of octopus “balls” gather to tend their brood.

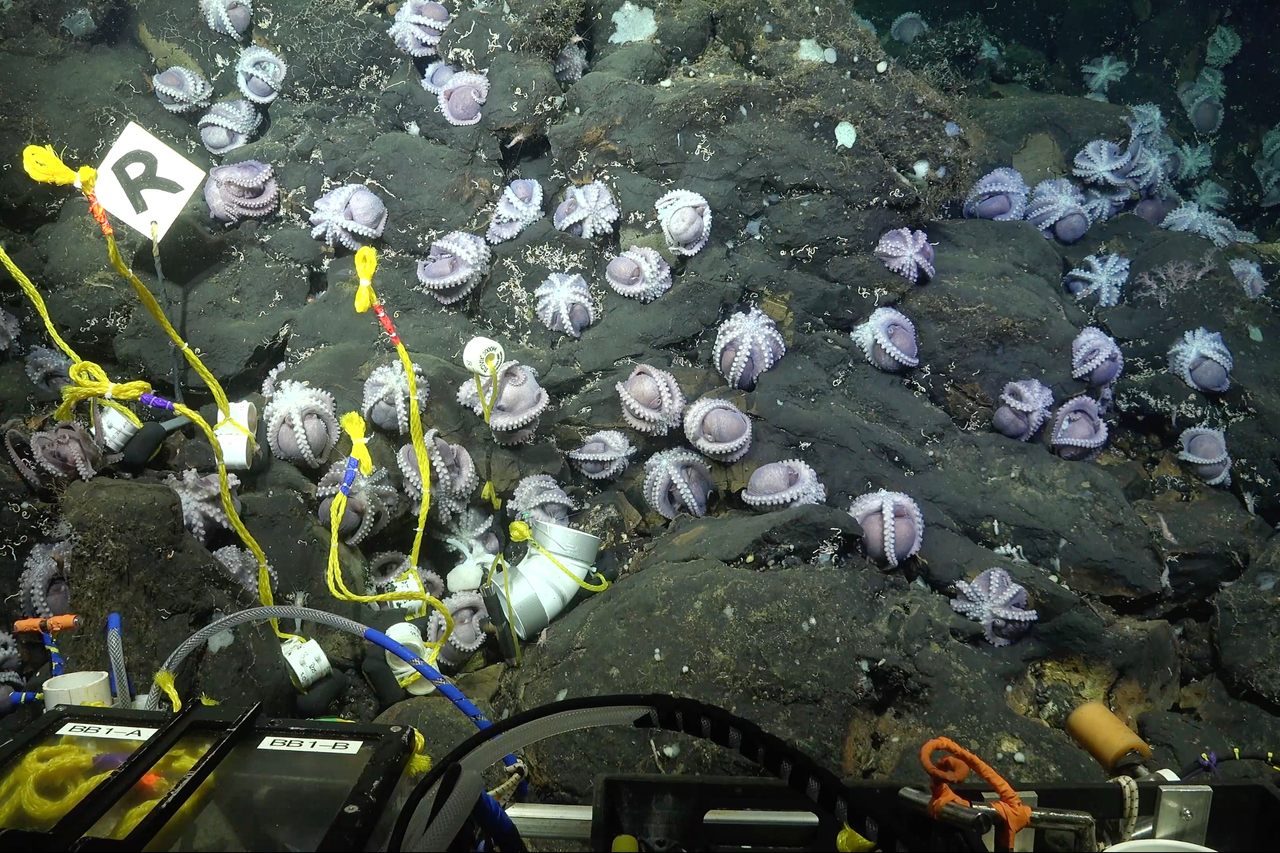

Octopuses are solitary creatures—usually. During a 2013 expedition, the headlight of a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) cut through the dark waters of the deep sea, exploring underwater mountains—or seamounts—nearly two miles below the surface off Costa Rica’s Pacific Coast. Moving past sponges, pink sea lilies, and ghostly-white crabs, the ROV’s light shone on a surprising sight. Female octopuses, rolled into balls in a defensive position to protect their eggs, were clustered together on the rocky terrain, gently swaying back and forth. They were gathered around the warm waters of a hydrothermal spring. The water temperatures around these lesser known, more temperate relatives of broiling-hot deep sea vents are about 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

But the scientists didn’t see any live young, and the eggs looked oddly milky, says marine biologist Jorge Cortés of the University of Costa Rica. They suspected that the deep sea spring wasn’t hospitable to baby octopuses.

In 2023, researchers sent another ROV down in search of the nursery. When they found it, the control room erupted in excitement, says expedition coleader Beth Orcutt, an oceanographer at the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences in Maine. Researchers gathered around the screen to watch hatchlings emerging from eggs alive and well. As the ROV continued to explore the area, it found another thriving nursery. Together, the sites were home to perhaps hundreds of mother octopuses.

These were no ordinary moms: Team members later determined they were a new species of octopus, only the second in the world known to form nurseries around deep sea springs. Over the course of two 20-day expeditions, the team also discovered a network of these deep sea springs in the area, as well as three additional new species of octopus that were part of the larger ecosystem.

“The deep sea is far more diverse than people imagine,” says expedition coleader Cortés. “I think this shows how little we know about the deep sea. Every time you go, you will find something new.”

The octopus nursery’s location was of particular interest to the team. During the 2013 survey, researchers identified a low-temperature hydrothermal spring in the area, the first of its kind ever found. The 50-degree water released by such springs is significantly warmer than the near-freezing water surrounding it. And unlike oxygen-deprived, superheated hydrothermal vents, these springs hit a sweet spot of warmth and oxygen—“like Goldilocks,” says Orcutt. Tube worms, giant mussels, and yeti crabs have evolved to live in the extremely low-oxygen, high-temperature environments of hydrothermal vents, which can reach up to 750 degrees Fahrenheit. “That’s not the octopus,” says Orcutt. “Octopus like something that’s warm but still has oxygen in it.”

But finding these springs is no easy task, says Orcutt. Unlike hotter deep sea vents, these warm springs are hard to find with traditional temperature-scanning methods. Instead, researchers use a combination of clues in the bathymetry, or the topography of the seafloor, to identify likely areas, and then deploy the ROV like a scout.

“Imagine if you will, a muddy bottom with outcrops that range in height from about 50 meters [165 feet] to 900 meters [2,950 feet] coming up out of the seafloor,” says Orcutt. “Imagine you’re walking in the dark through a flat desert and then you come upon a hill and all you have is a flashlight to help you see. That’s kind of what it feels like.” Except, your flashlight is attached to a remote operating vehicle over a mile under the sea.

During the 2023 explorations, researchers found three hydrothermal springs supporting biodiversity in the surrounding waters, from a nursery of skate fish—lovingly termed a skate park—to mating glass octopuses, to new species. Invertebrate expert Janet Voight at Chicago’s Field Museum and Fiorella Vásquez Fallas, an undergraduate at the University of Costa Rica, determined the foot-long and “hefty” new species of octopus found near the vents is in the same genus as the only other known species of vent-loving octopus, Muusoctopus robustus, which was discovered off the coast of California in 2018. The team calls the Costa Rican octopus, which is distinct from M. robustus, the Dorado Octopus after the football field-sized outcrop where it was discovered.

One of the other three new octopus species discovered during the expeditions, pale in color and with a uniquely bumpy body, is just “weird,” says Voight. As with the other octopuses found during the expedition, Voight and Vásquez pointed to differences in anatomical traits—such as the number of suckers—to identify them as new species. Now, they are using molecular analysis to confirm their conclusions before they formally name them.

With over half the scientists and students on board hailing from Costa Rica—a rarity, says Cortés—the expedition wasn’t just about exploration of the deep, but empowering local researchers and the next generation. Over 300 specimens collected during the 2023 expeditions will stay at the Zoological Museum at the University of Costa Rica, providing Costa Rican researchers—including those still in school—direct access to their deep sea heritage.

The survey of biodiversity, including the discovery of the new octopus species, was part of a much broader objective for the team: to document an entire deep sea environment.

“People think of the deep sea as kind of this deep, muddy pit that there’s nothing living in, but there are beautiful, spectacular physical features,” says marine ecologist James Berry, of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute; Berry was not involved in the study. “Some of the natural wonders we see on land also exist in the deep sea. Exploration will help us understand what’s down there, how it’s important to us, and how we might be able to protect it for future generations.”

Protecting the octopus nursery and the surrounding area is more urgent than ever as deep sea mining projects ramp up around the world. “We need all hands on deck to try to understand the deep sea,” says Orcutt. “The deep sea is often left out of conservation plans, and that needs to change.”

She adds: “Clues about the origins of life on Earth are found in the deep sea, so if we don’t study this system, we’re not going to understand life on Earth.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook