Eat Like a Medieval Saint With Her Recipe for ‘Cookies of Joy’

St. Hildegard was a mystic, healer, and passionate proponent of spelt and nutmeg.

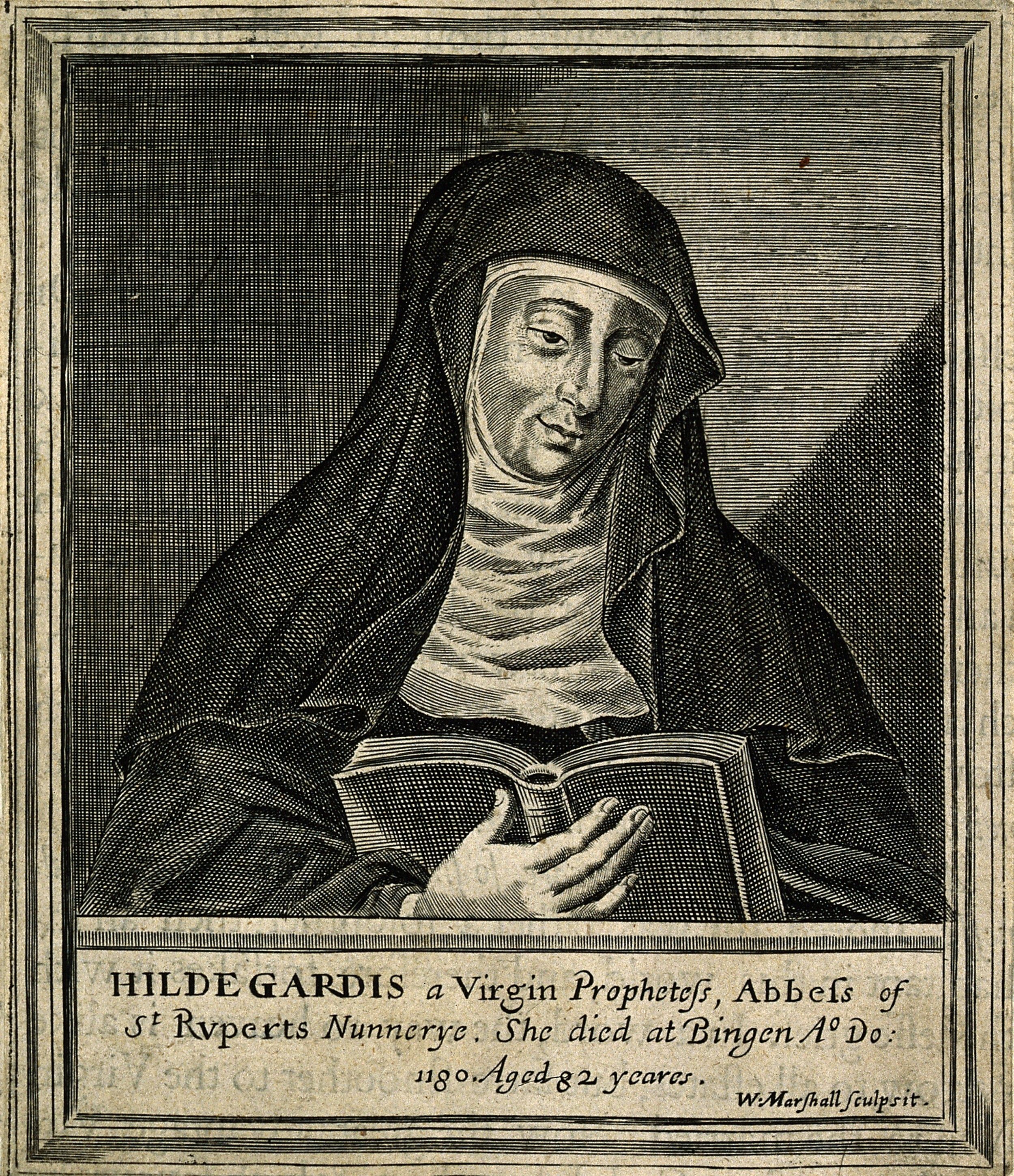

Hildegard of Bingen was a 12th-century nun, mystic, prophet, and healer. She led an abbey, communed with God, advised royalty, and chastised emperors. She also made cookies.

Committed to a hermitage from the age of eight, Hildegard rose to prominence as a result of her divine visions. In a series of books, she relayed messages from God that ranged from the metaphysical to the practical. Along with fiery depictions of the world as a “cosmic egg” enveloped in the flames of God’s love, Hildegard’s books included divinely inspired recipes said to cure everything from leprosy to lung disease to the common cold.

Hildegard’s pharmacopoeia revolved around the kitchen and the garden. In her books Physica and Causes and Cures, she outlines herbal and culinary remedies for a vast array of ailments. For a weak heart, she proposes a daily teaspoon of “wine for the heart,” consisting of boiled parsley, honey, and wine. For stomach pain, a nightcap of wine mixed with powdered ginger, galingale (a ginger relative from Southeast Asia), and zedoary (another ginger cousin, from India). And for matters of melancholy, she offers her “cookies of joy” (or “nerve cookies”), wielding the key ingredients of spelt flour, nutmeg, cinnamon, and cloves to “calm all bitterness of the heart and mind, open your heart and impaired senses, and make your mind cheerful.”

While Hildegard’s life was exceptional—in addition to her books, she composed around 70 pieces of music and invented her own language—her dietary remedies were probably the least unusual thing about her. According to medical historian and physician Victoria Sweet, who compared the saint’s medicinal writings with contemporary manuscripts, Hildegard’s work is far from the mystical healing one might expect. Rather, it’s an excellent window into the world of medieval monastic medicine, where on-site gardens, vineyards, and kitchens yielded healing tonics, broths, and baked goods. The Hildegardian pharma-bakery didn’t just prescribe cookies to counter depression, but also recommended licorice-flavored cookies for nausea and ginger varieties for constipation.

Whether or not you believe Hildegard communed with God, she was blessed with a unique education in the healing arts. Born on the cusp of the prosperous 12th century, she was poised to reap the benefits of a booming era in European history. “It was just this far-out time,” Sweet says, adding that Hildegard was born into an era of scholastic advancement, population growth, and agriculturally beneficial weather. Although she would have lived separate from the men at the coed Disibodenberg monastery, Sweet notes that Hildegard would have likely communicated with educated monks and had access to the library, the medicinal garden, and the infirmary. The result was an education that rivaled those of leading medieval minds.

“So Hildegard would have gotten the Latin-age academic tradition … the existing infirmarian tradition, and then, third, this sort of medical-women tradition with the midwives and the healers,” Sweet says. “So what she ends up giving us is a wonderful mixture of all that.”

The recipe-remedies within Hildegard’s medicinal texts show a mingling of herbal medicine and Greco-Roman humoral theory. Hildegard’s treatments blended the metaphysical aspects of spirituality with the physical aspects of the body and the earth. In addition to the interplay of black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood, Hildegard saw all ailments as imbalances of earth, fire, water, and air, and how they impacted what she called the body’s viriditas, or “greening power,” to heal itself. The key was identifying whatever imbalance threw off this power (was the body too hot? too dry? too cold?) and rectify it with herbal wines, soups, syrups, and, of course, cookies.

In the case of her cookies of joy, Hildegard’s target was an overabundance of black bile, what she considered to be the source of evil and melancholy. Her weapons against this darkness were spelt and spices such as nutmeg, cinnamon, and clove. Spelt, in Hildegard’s words, is a “hot, rich, and powerful” grain that “creates a happy mind and puts joy in the human disposition.” Spices such as nutmeg would have a similar effect, opening up the heart, freeing the mind and senses, and establishing an overall joyful disposition.

While the emotional effects and poetic descriptions may sound suspect, there is real nutritional value within the cookie recipe. “When I read Hildegard, like, 30 years ago, I was saying, ‘Yeah, but what the hell is spelt exactly?’” Sweet laughs. “Then about the last 10 years, we have all this stuff with gluten enteropathy and emerging knowledge about the genetic manipulation of our wheat. Our wheat is a mess.” Sweet points out that spelt is an ancient, “unmessed-with” grain, so some people who struggle with digesting wheat can eat it.* Meanwhile, she says, the spices were likely meant to serve as “uppers,” offering a boost of stimulation.

“More of her cures worked than didn’t,” Sweet says, noting that many of her herbal remedies are as timeless as those within traditional Chinese medicine.

It’s hard to tell if Hildegard practiced what she preached. While she wrote that she was “constantly fettered by sickness,” she lived into her 80s, a miraculous run for the medieval era and suggestive of a healthy life. Sweet thinks Hildegard’s many alleged illnesses may have been a defense against misogynists and nonbelievers. “She whined all the time about her health,” Sweet says. “But it’s hard to imagine somebody who really was sick doing everything that she did—writing and composing and traveling—so I kind of tend to discount that. She describes herself as a sick, little, woman … I think that poor, little woman trope of Hildegard was for safety. She didn’t create all this stuff. God inspired her. ‘If you have a problem with me, take it up with God.’”

Hildegard appears to have doubled-down on her humble, frail persona at moments when she wielded her power as prophet. For instance, she was struck by a mysterious illness after the abbot at Disibodenberg initially refused to let her leave and found her own monastery. (The abbot was reluctant to lose the prophet-nun, who’d attracted a fair share of visitors and revenue.) Hildegard lay in bed for months, unable to do anything until the will of God (i.e., her founding her own abbey) was completed. When the abbot finally relented, she made a miraculous recovery.

Hildegard also sometimes channeled this meek servant persona when speaking truth to power. In Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine, Barbara Newman describes a sermon Hildegard gave in the German city of Trier during a preaching tour in 1160. “It begins with a typical protestation of modesty: ‘I a poor little figure without health or strength or courage or learning, myself subject to masters, have heard these words, addressed to the prelates and clergy of Trier.’” The “poor little figure” then launched into a harsh rebuke of these very prelates and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa (whom Hildegard advised and never hesitated to criticize).

Whether she was a divinely inspired mystic or an intelligent, shrewd healer and leader (or all of the above), Hildegard’s works continue to influence healthcare today. In Germany, some doctors still practice Hildegardian medicine. In the town of Allenbach, for example, a clinic focuses exclusively on Hildegardian treatments. Beyond the realm of modern medicine, though, Hildgard’s work is alive and well at monasteries. At St. Hildegard Abbey, founded by Hildegard herself in Eibingen in 1165, nuns carry on her culinary traditions, making and selling “cookies of joy” along with galangal-ginger cookies, wine, and a selection of herbal liqueurs and teas.

If you don’t plan to visit the Rhineland soon, you can still try Hildegard’s “cookies of joy.” The below recipe yields a delightfully aromatic treat, with a spicy gingerbread flavor and a satisfying crunch. Hildegard would’ve recommended pairing them with a spelt coffee, but a cup of herbal tea will do. Sweet, who’s made the cookies, says the recipe holds up, but she attributes their mood-boosting powers more to their flavor than anything else.

“They were good. I mean, how bad could they be with butter and sugar?”

Cookies of Joy

Sam O'Brien

Ingredients

- 12 tablespoons butter

- 3/4 cup brown sugar

- 1/3 cup raw honey

- 4 egg yolks

- 2 1/2 cups spelt flour (you can usually find it in the baking aisle)

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 1 tablespoon nutmeg

- 1 tablespoon cinnamon

- 1 teaspoon cloves

Instructions

-

Melt the butter, then add it to a medium bowl with the sugar, honey, and egg yolks. Beat gently, then fold in the rest of the ingredients. Refrigerate the dough for an hour.

-

Flour a surface and then roll out the cookie dough until about a 1/4 inch thick. Cut the dough into small circles using a cookie cutter or an upturned glass.

- Line a baking sheet with parchment paper, then bake at 375 degrees Fahrenheit for 10 minutes, or until a golden-brown. Let cool, then enjoy.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook