The Humble Brilliance of Italy’s Moka Coffee Pot

In the era of pods, the iconic item has become an endangered species.

Bialetti, the Italian maker of the moka pot, a stovetop coffee machine and one of the most iconic kitchen appliances ever created, announced in 2018 that the company was in major trouble—tens of millions of Euros in debt, unpaid salaries and taxes, revenues that are way down and look to be staying that way. In a press release, the company said there are “doubts over its continuity.” (Update: Bialetti sales have been on the rise since then.)

The moka pot is a symbol of Italy: of postwar ingenuity and global culinary dominance. It is in the Museum of Modern Art, the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, and other temples to design. It is in the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s most popular coffee maker, and was for decades commonplace to the point of ubiquity not only in Italy but in Cuba, Argentina, Australia, and the United States. It’s also widely misunderstood and maligned, with approval in the modern coffee world coming perhaps a bit too late, in only the past few years. Get one while you can.

Italy’s place in the history of global coffee culture is substantial, but for different reasons and in different ways than most people probably think. The various species of Coffea, the seeds of which are dried, roasted, and ground to make coffee, are native to east Africa, particularly Ethiopia. Coffee as a beverage first shows up in the historical record—which is not necessarily to say that it wasn’t consumed in its native Ethiopia first—in what is now Yemen. It spread quickly throughout the Middle East, North Africa, and firmly established itself as part of the culture in what are now Turkey and Iran.

Europeans were late to the coffee party, but Italy, sharing the Mediterranean with the Arab and Greek worlds and not really very far from North Africa, was probably the gateway for coffee to spread westward. But for centuries after its introduction to Venice in the early 17th century, coffee was seen as an Arab affectation, something foreign and alternately exotic and threatening. “It was thought of as an Eastern thing, in that Orientalist way of thinking,” says Peter Giuliano, the chief research officer for the Specialty Coffee Association and a former co-owner of the influential Counter Culture coffee company.

Until the late 19th century, Italians drank coffee in pretty much the same way as the Turks. Coffee and water are combined in a long-handled metal pot called a cezve and held over a heat source; the mixture combines as it boils, and is poured into small cups, where the grounds settle to the bottom. Italy never really left behind the idea of small amounts of very strong coffee. The thinner, lighter, larger mugfuls of coffee were more a northern European, and North American, thing.

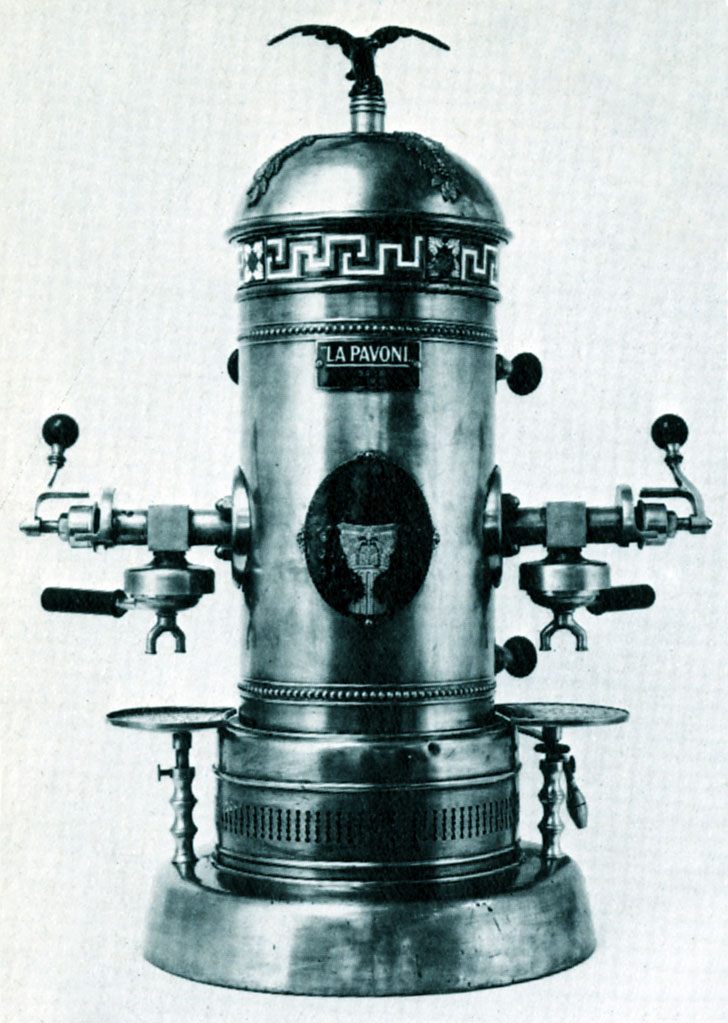

Italians began coming up with their own gadgets for brewing coffee in the 19th century, but the biggest by far was the idea of applying pressure to coffee in order to create a strong, and more importantly fast, drink. This is the age of steam, a miraculous source of power that can unlock the world, and though it’s not entirely clear who originated the idea of using steam to brew coffee, certainly it was in Italy that it was popularized. The first known patent for a machine we might now recognize as an espresso machine was registered by Angelo Moriondo, who created a giant complicated steam-driven machine in 1884, but who never bothered to manufacture it. Luigi Bezzera, from Milan, modified the Moriondo patent, and his design was further modified (though less so than Bezzera’s) by Desidiero Pavoni, whose La Pavoni introduced the world to espresso in 1906, at a world’s fair held in Milan.

Pavoni’s device was a large complex metal contraption that worked, roughly, like this. A compartment of water on the bottom of the device is heated by placing the entire thing on a flame. A tube leads up to a circular puck of ground coffee; because the entire device is sealed, as the water boils, pressure forces steam and hot water up through the tube and through the coffee grounds. That pressure brews coffee much more quickly than without the pressure, and the fast-brewed, strong coffee flows into a chamber, to be poured into cups.

This is, not coincidentally, the exact same way the moka pot works, though on a much smaller scale.

Pavoni’s device was a huge hit, but it was incredibly expensive and cumbersome. It wasn’t at all suitable for use at home, which was fine for a few decades because coffee had never been a beverage consumed at home anyway. It was, as in the Arab world, a communal activity. (As a side note, the fact that it was a communal and foreign-seeming ritual seems to have scared those in power in the Catholic world quite a bit at first; it took an official approval from Pope Clement VIII in 1600 to clear coffee’s dangerous connotations.) Coffee was too expensive, and the newly popular Pavoni brewing devices unsuited, to be making coffee at home.

Jeffrey T. Schnapp outlines the history of the moka pot in a 2001 paper called The Romance of Caffeine and Aluminum. In 1918, he writes, a Piedmontese metalworker named Alfonso Bialetti returned home after a decade spent working with aluminum in France. Industrial production of aluminum was new, then; methods for working with it at any real scale had only been developed in 1886. He opened a shop, crafting strong, lightweight aluminum versions of pots and pans that had previously been only available in iron.

Legend has it that the idea for the moka pot came from a laundry boiler, though that’s not confirmed. What is known is that the La Pavoni device was very trendy, and there was also a precedent for a smaller coffee machine: the napoletana. The napoletana is a small metal device with three sections: a chamber of water, a small puck of coffee in the middle, and a chamber on the other end for brewed coffee. Water is heated up with the water chamber on the bottom, and then the entire device is flipped upside-down, allowing the hot water to drip through the coffee beans and gather as coffee in the previously empty chamber. No pressure is involved.

Bialetti worked on some combination of the La Pavoni and the napoletana for a few years and in 1933 patented his Bialetti Moka Express. It’s three-chambered, like the napoletana, but uses steam power to force hot water through the coffee, like the La Pavoni. The characteristic hourglass shape, with the eight-sided chambers, was there from the beginning.

But the Moka Express design—today, “Bialetti Moka Express” is the specific product, while “moka pot” is the general term for this type of coffee maker—took a while to catch on. Italy still had to get embroiled in a couple of World Wars, and then recover.* By the 1950s, Italian design had some amazing advantages. All of the factories set up to create war materials were at a loss for products to make, as were a generation of skilled manufacturers. Vespa, Fiat, and Alfa Romeo designed incredible vehicles. And Bialetti’s Moka Express, which still boasted a futuristic and clever design, suddenly took off.

Post-war Italy had a surging economy, a growing middle class, and the same access to the world’s products that the rest of Europe boasted. Alfonso Bialetti’s son, Renato, came back to Piedmont in 1946 to take over his father’s shop, and decided to stop making everything except one product: the Moka Express. The newly low price of aluminum and coffee, and a growing middle class of people who could buy products like this, made the moka pot a perfect device for the time. Renato was also a pretty shrewd businessman; in 1953, he commissioned the drawing of the company’s logo, L’omino con i baffi, “the little man with the mustache,” which has since been inseparable from the Moka Express. The Moka Express was “the first way that Italians could realistically make coffee at home that was some approximation of what they could get outside,” says Giuliano.

Over the next 60 years, the moka pot would conquer the world. As of 2016, the New York Times notes that over 90 percent of Italian homes had one. It became so iconic that Renato Bialetti, when he died in early 2016, was actually buried in a large replica of the moka pot. It spread to some countries with large Italian immigrant populations, becoming common in the Italian-American communities in and around Philadelphia, New York City, and Chicago. Argentina and Australia, both of which received large waves of Italian immigration in the 20th century, are also home to plenty of moka pots. The Argentinian company Volturno has been so successful that the moka pot in Argentina is sometimes called a Volturno.

Cuba is a more interesting one. Coffee has a long history in Cuba; the climate, hot and wet with plenty of elevation, is ideal for growing coffee, and the crop has been grown there since the mid-1700s. Up until the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Cuba was one of the world’s great coffee producers, and also one of the world’s great coffee cultures. Coffee preparation varied; in the cities, espresso was common, and on coffee plantations, it was more typical to grind beans in a mortar called a pilón and steep with hot water before straining out the grounds with cloth.

After the 1959 revolution, food rations came for coffee as well. Coffee is currently rationed to four ounces per person per month, coming in two packets. But these rations aren’t pure coffee; they are mixed with fillers, sometimes toasted chickpeas (cafe con chicharo) to make the small amounts go further.

Because the amounts of coffee are so low, and efficiency so important, Cubans began tinkering to come up with ways to create the best possible coffee with the materials they have. Cuban coffee in a Cuban or Cuban-American home is almost always made with a moka pot; the Cuban concoction cafecito is made by quickly whipping the first few drops of moka pot coffee with sugar, creating a paste that both flavors the coffee and simulates a classic espresso foam. Even outside of Cuba, where the coffee is not likely to be mixed with toasted beans, Cuban coffee is typically very sweet and very strong, almost always made with a pump machine in coffee shops and a moka pot at home.

The moka pot’s struggles began in the 1990s, and came in two forms. One, I think, is very interesting, but is not as large a factor in the demise of the moka pot as some might believe. The other is very boring and very obvious and is almost certainly the big problem. The latter is that people, in Italy and elsewhere, love coffee pods. Coffee pods, especially Nespresso, are wildly popular in Italy, because they are easy. I have very little else to say about coffee pods.

The former problem, the more interesting one, took place within the coffee-nerd world.

Inspired by Italian espresso bar culture, Starbucks almost single-handedly changed the entire concept of coffee in America. And the moka pot was not part of that. The espresso machine, which uses mechanical pressure (via pumps and/or levers), was the device used to make coffee in Italian coffee shops; the moka was strictly for the home. “In the ‘90s and early ‘00s, having some sort of ‘authentic’ Italian coffee chops were part of what was exciting and interesting about coffee,” says Giuliano, who lived through this phase at Counter Culture. In the 1990s, coffee shops, which greatly informed coffee consumption in the U.S. in general, looked to Italian coffee bars.

This ignored that Italians never really made espresso at home. They used the moka pot. Espresso machines, then and now, are gigantic, expensive, difficult to use, and incredibly inefficient from an energy perspective. They do not really make sense for the home. But Americans tried anyway, replacing their Mr. Coffees and French presses with underpowered home espresso machines, ignoring the entire time that there was another option, the one Italians used all along.

After the Starbucks boom, American coffee culture changed rapidly, eventually coming to embrace drip coffee, especially a lighter, more acidic style common in Scandinavia and Japan. Espresso stayed, of course—with the glaring exception of the moka pot, Americans never really stopped looking to Italy for coffee, and even today most of the “serious” espresso machines come from Italian companies.

The moka pot, which in the U.S. had previously had a light following, especially for Italian-Americans, became an object of extreme derision. Coffee purists cried that it couldn’t possibly produce espresso; the moka pot, like the La Pavoni, uses about 1.5 bars of pressure, while a pump espresso machine ideally hits about nine bars. This is, of course, a ridiculous argument; there is no actual definition of espresso, and in any case, the moka pot is at most a second cousin to the espresso machine. There’s no particular reason to compare a steam-driven stovetop machine to a pump-driven electrical device, but coffee people did.

The past few years have changed that, a little bit. Coffee people have softened their stance, and recognized the moka pot for what it is: an entirely different branch of the coffee machine tree, a very old, very clever, and very economical way to make coffee. The previous complaints about the moka pot fell away, and it is increasingly, in coffee circles, given credit for all its strengths.

The nice thing about the moka pot is that it can create a very nice cup of strong coffee, and that the equipment you need is wholly affordable. Moka pots cost about 30 bucks, and by using good coffee and a bit of technique, you can make as good an example of moka pot coffee as anyone in the world.

The rediscovery of that fact by coffee nerds bodes well for the future of the moka pot, despite the troubles of Bialetti, the company. It remains a cool, inexpensive, highly functional example of mid-century modern design. In the same way that the single-cup pour-over cone was rediscovered and prized, sparking a whole new round of sales, maybe the moka pot is due for some revitalization and new trendiness. It seems impossible, or at least undesirable, for such a cool gadget to die.

*Correction: We originally referred to Italy losing two World Wars. That was a big mistake. Huge.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook