Why a Minnesota Pastor Wrote an Obituary for a Lutefisk Dinner

RIP Faith Lutheran Scandinavian Dinner, 1947-2017.

Few obituaries are written for laughs. Yet a recent obituary penned by Reverend John Klawiter of Forest Lake, Minnesota’s Faith Lutheran Church was intended to evoke giggles as well as grief. The obituary wasn’t for a person, but for a dinner the Church had held for the last 70 years.

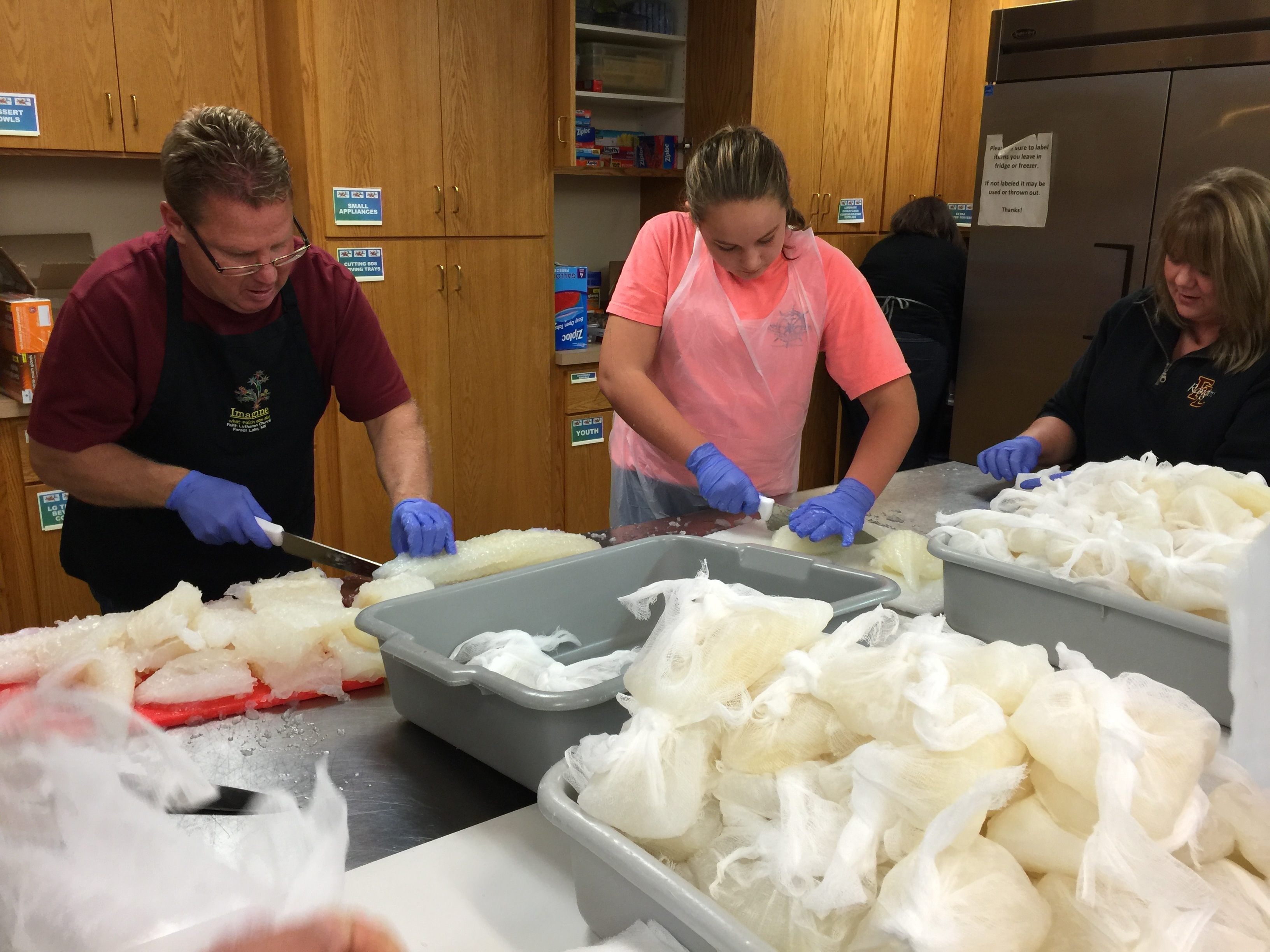

This wasn’t any old dinner. The church’s annual function featured Scandinavian specialties, such as lefse, a potato flatbread, and lutefisk, a notorious treat of dried cod or other whitefish reconstituted in a lye bath. As a result of heavy immigration from Norway, Sweden, and Finland in the early 20th century, many Minnesotans celebrate the holidays with Scandinavian cuisine. In fact, more of the ammonia-scented specialty is eaten in the Midwest than in its ancestral home. Faith Lutheran church was no different. For 70 years, on the second Tuesday of December, hundreds of volunteers prepared lutefisk, lefse, boiled potatoes, and meatballs for still-more hundreds of diners. After all, Klawiter says, Faith Lutheran was once known as the Swedish Lutheran church.

This year, however, there will be no lutefisk. “Faith Lutheran Scandinavian Dinner, also known as ‘The Lutefisk Dinner’ or ‘Holy Tuesday,’ has peacefully died at the age of 70,” Klawiter wrote in the Forest Lake Times obituary. Last year’s event, he says, was the last straw for many volunteers, especially those getting too old to prepare several hundred pounds of fish. “They made it through last year … and the next day they were just exhausted.” Even after outsourcing the lutefisk preparation to the company that sells the fish, the event was a lot of work.

While the dinner once served 800 diners, attendance had dwindled to around 500. Part of the drop can likely be attributed to fewer Minnesotans growing up on lutefisk: Its gelatinous texture and pungent odor prove steep barriers to those unfamiliar with it. “You put a plate of lutefisk in front of the average person on the street, you probably wouldn’t get too many takers,” says Klawiter.

Klawiter wrote an obituary, he says, because he needed to do something attention-grabbing. For many parishioners, the church dinner on the second Tuesday of the month was a given. (“That’s the day that they come get the lutefisk.”) Klawiter feared they’d all still show up if he just issued a press release, so he opted for a half-somber eulogy to the fish-filled event.

But for those still hankering for a lutefisk fix, there’s hope. While Klawiter’s obituary notes that Faith Lutheran’s Scandinavian Dinner was “preceded in death by numerous cousins,” it’s “survived by a few remaining siblings.” These siblings and cousins are, of course, other church dinners serving lutefisk. While Klawiter says the local love for lutefisk endures, it’s almost a cautionary tale. “If you really value this tradition,” Klawiter says, “help out in another church. Help them put their meal on.”

While Klawiter knows people will miss the Scandinavian Dinner, he thinks it was the right decision. He also emphasizes that it presents new opportunities for other church projects and events. In a pulpit-ready voice, he tells me: “There’s death, and new life comes out of that.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook