After the Last Great Auks Died, We Lost Their Remains

Before they went extinct, great auks were some of the world’s most fascinating creatures.

If the great auks had been able to stay on Geirfuglasker, in the end it would not have saved them. Sheer-sided, surrounded by rough seas, Geirfuglasker—Great Auk Rock, in Icelandic—discouraged visitors. Men had found the fat, goose-sized birds there anyway, but the island was far enough out to provide a measure of safety for a while. But then, in 1830, a volcanic eruption sank the island beneath the water.

The great auks migrated to Eldey, a rough wedge of rock 14 miles closer to Iceland’s Reykjanes peninsula. There was only one spot to land a boat on Eldey, but men made it onto the island, from time to time, to hunt the birds. Once, these birds had been sought for their down or the meat of their large breasts. When they became scarce, collectors competed to get hold of one. In June 1844, a group of Icelandic hunters rowed out to Eldey in search of great auks at the behest of collector and dealer Carl Siemsen. They climbed to the island’s flat top and spotted a single pair.

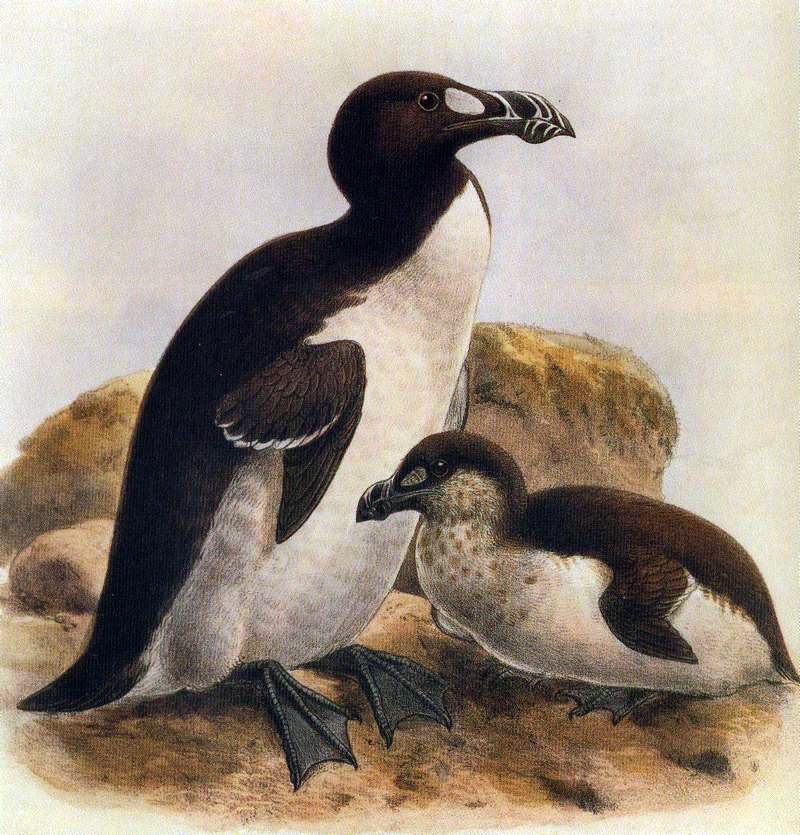

The birds’ wings had long ago evolved for the water rather than the air. On land, where they came to lay their eggs, the birds could only waddle toward the water, wings tucked close to their bodies, in an attempt to escape. “They uttered no cry of alarm,” one of the hunters later recalled, “and moved with their short steps, about as quickly as a man could walk.”

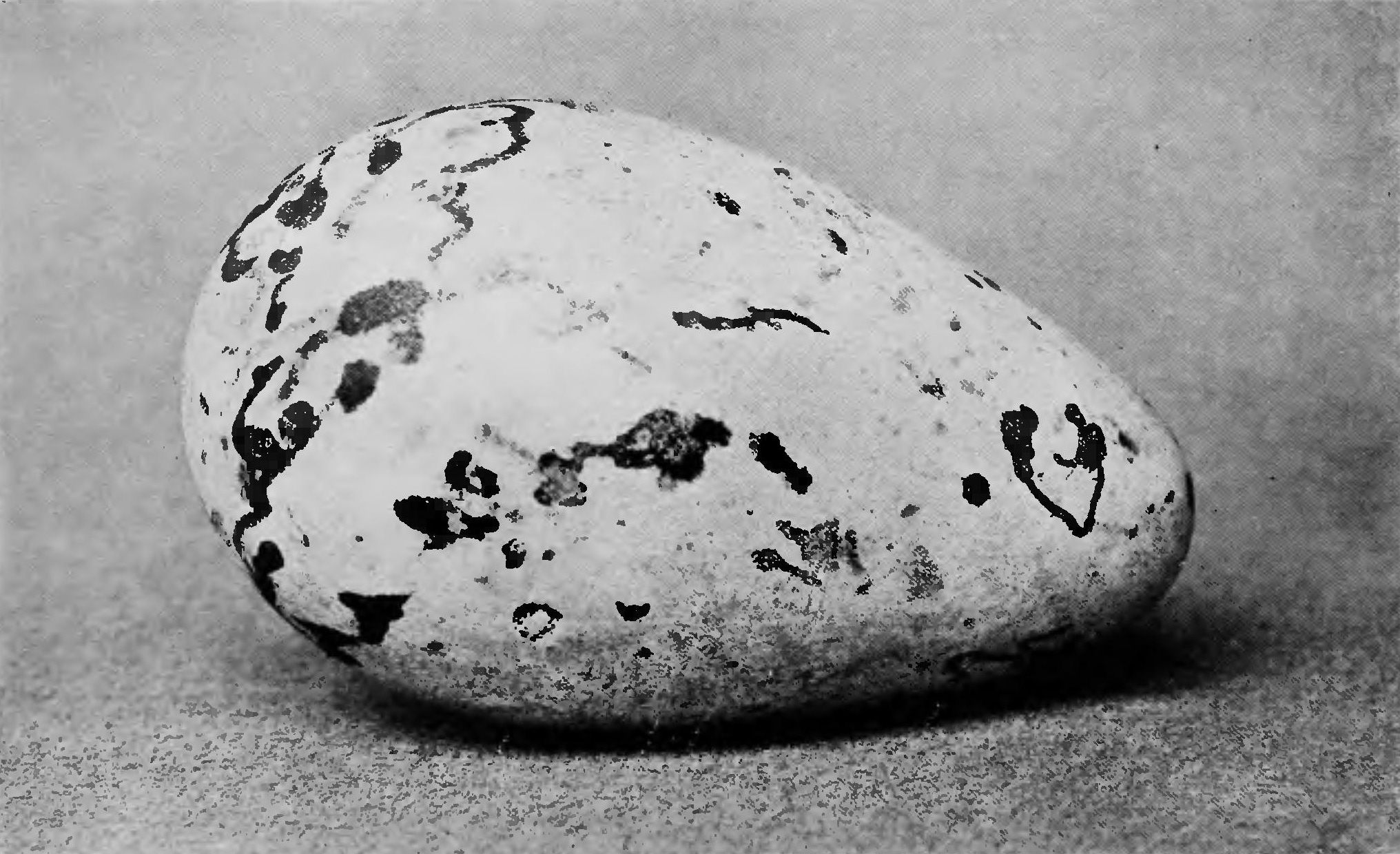

It was easy to catch the birds and break their necks. They had been caring for an egg, already crushed by the time the hunters found it.

Those great auks were the last of their species, or at least the last two definitively seen alive. After that, occasional reports of great auk sightings surfaced, but soon it became clear that the species, the last flightless bird in the northern hemisphere, had gone extinct.

The remains of those last two birds never made it to Siemsen. The hunters sold the bodies to an apothecary in Reykjavík, who skinned the birds, preserved their internal organs (in whisky, according to legend), and sold them. Today, the Natural History Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen holds their eyes and organs. But in the chaotic 19th-century trade in great auk specimens, no one kept track of what happened to the coveted skins.

Jessica Thomas, who goes by @Aukward_Jess on Twitter, first heard about the disappearance of the last great auks’ skins when she spent a year at the University of Copenhagen as part of her doctoral work on ancient DNA. She wondered if it might be possible to find them. The skins were so valuable that they almost certainly ended up in a museum somewhere.

Thomas was already gathering DNA from great auk specimens, in search of biological data that could help explain their extinction. But, she thought, perhaps she could use her data to the solve another centuries-old mystery: the fate of the remains of the last two great auks.

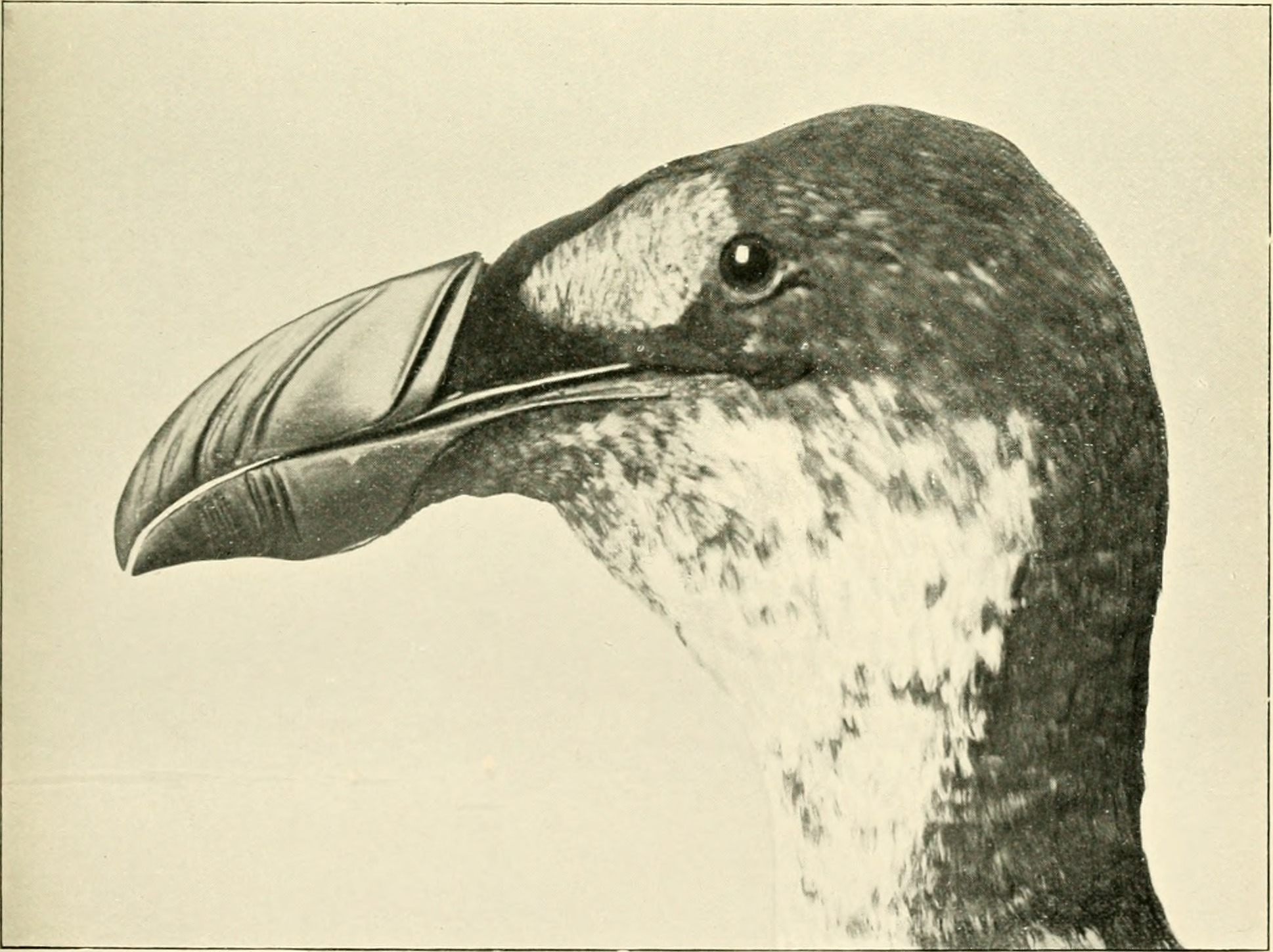

Great auks were beautiful birds. Their bellies were white and their backs a slick black. They had large white spots on their heads, overlapping small, intent eyes. Their oversized beaks had parallel grooves running down each side, and their eggs were spotted with drips and drabs like a Jackson Pollock painting.

They lived in the cold waters of the North Atlantic and in summer months congregated on isolated islands in large groups. Off the coast of Newfoundland, before Europeans arrived, the Beothuk people paddled out to a small rock 30 miles to sea to collect their eggs. The birds were powerful symbols for the people of North America’s Atlantic coast: Their beaks have been found in human graves, including one where 200 beaks covered the interred.

European sailors came across the birds on that outcropping, later named Funk Island for the smell of the guano layered there, in the 17th century. On expeditions of exploration or fishing voyages, they went to Funk Island as if it were a commissary. The large birds were easy to catch. Craving a supply of fresh meat while out at sea, sailors herded them onto the boats. The Funk Island auks survived this assault for hundreds of years, but at the end of the 1700s, when settlers started killing them for their down rather than just their meat, Newfoundland’s great auks was doomed.

“On the island, which is just a bald rock, there’s a cairn of stones,” says William Montevecchi, who studies the ecology of marine and terrestrial birds at Memorial University of Newfoundland. He spent many years conducting research on Funk Island, now an ecological reserve mostly off-limits to visitors, to protect the gannets, murres, and other seabirds that still live there. Accounts of the last encounters with the island’s great auks describe mounds of dead birds piled up, parboiled and discarded after their down had been harvested for European blankets and pillows. Montevecchi found a lingering sign of that slaughter. Great auk islands tended to be places of bare rock coated with guano, but this one has a meadow on top, grown from, in Montevecchi’s words, “composted great auks.” “It’s a mysterious place,” he says, “unique on the planet.”

As great auks dwindled in number, they became more sought after than ever before. By the early 1800s, naturalists had noticed that auks were becoming rare, which set off the scramble among museums and amateur collectors to obtain one. In London, Stevens’ Auction Room became famous for its auk auctions, and mounted auks became status symbols. As Errol Fuller writes in his book The Great Auk, “Kings and princes became Auk owners.” Carl Fabergé created a tiny auk statuette, from rock crystal with ruby eyes, that’s still in the Royal Collection in England.

Soon, mounted specimens, about 80 of which exist today, were all that was left. Reports of real-world sightings took on a mythical quality. In 1848, four years after the Eldey auks were killed, a group of Norwegians were rowing between two tiny islands off the country’s northeastern edge when they saw four strange, swimming birds. They shot one, hoping to examine it more closely. It was a large bird, with a white spot beneath its eye and unusually tiny wings. Months later, one of the men saw a drawing of a great auk and had a flash of recognition. But there was no proof he had encountered one. The men had dumped the body on the shore, but when they returned to retrieve it, it was gone.

We drove great auks to extinction before anyone had studied them closely, so there are major holes in our knowledge of them. Scientists are still uncovering new details, almost 175 years after the Eldey birds were killed. Montevecchi, for instance, analyzed bones from Funk Island to learn about the birds’ diet (primarily capelin, it turned out). One major question, though, is why they went extinct at all. Over-hunting is an obvious culprit, but scientists have wondered: Could environmental change played a role as well?

By examining their DNA, Thomas, who recently completed her doctorate at Bangor University and the University of Copenhagen, aimed to create a clearer picture of the size and genetic diversity of the world’s great auk population before the birds disappeared. But to solve the mystery of the Eldey auks, she’d need to focus on individual birds. In any genetic study, individuals are most easily identified by DNA from a cell’s nucleus. Thomas’s research focused on mitochondrial DNA, which is easier to obtain from older specimens but contains less information. Only if the genetic diversity of the auk population was high would her DNA samples lead her to the last, lost auks.

In his book, Fuller writes that each extant great auk specimen represents “a little tragedy all of its own.” He traces the history of dozens of preserved auks, and was able to identify five specimens that, based on their histories, could be the birds killed on Eldey in 1844. Among those, he suggested that one in Brussels and another Los Angeles could be the most likely candidates.

According to the recollection of a Danish professor, set down years after the birds left Iceland, the skins of the Eldey auks had been brought to the Congress of German Naturalists in 1844. From there, they may have passed through the hands of Israel of Copenhagen, a well-known auk dealer, to a merchant in Hamburg, to an Amsterdam dealer. By 1847, according to Fuller’s research, one of those skins belonged to the Brussels museum. The other made its way to a museum in Los Angeles over many more years. But it was unclear whether the skins Israel of Copenhagen had sold were in fact the Eldey auks.

In her larger study, Thomas had looked at 41 individuals and found little overlap among the sequences. Even in their mitochondrial DNA, the birds had enough genetic diversity that individuals could be distinguished from one another with relative ease. To try to identify the skins, Thomas extracted DNA samples from the esophageal tissue of the two Eldey auks along with a sample from one of their hearts, from among the portions still held by the Natural History Museum of Denmark. The genetic material from the esophagus of the male auk was a perfect match with one other specimen—the Brussels auk that Fuller had identified. But the DNA from the female auk, taken from her heart, did not match any of Fuller’s five suggestions. Only half of the mystery had been solved, and the female auks’ skin was still lost.

But Thomas believes she knows where it could be. The auk in Los Angeles once belonged to George Dawson Rowley, an amateur ornithologist who had traveled to Iceland to document the history of the Eldey auks. Rowley owned two auk specimens, which later became part of a quartet of auks sold by a London dealer. But, Thomas and her colleagues write in a paper published in the journal Genes, the auction house mixed up the four birds. It’s possible that the Los Angeles auk and another—now in a Cincinnati museum—may have been confused for one another. Thomas plans to test the DNA of the Cincinnati auk in the coming months. By this summer, the mystery of the auk skins may be solved.

Even then there will still be open questions about the larger loss. “Understanding more about its extinction, as a recently extinct species, has implications for understanding present-day threats to biodiversity,” says Thomas. We can learn more about why and how species might disappear by studying one that was wiped out in our own time than one that went extinct thousands of years ago.

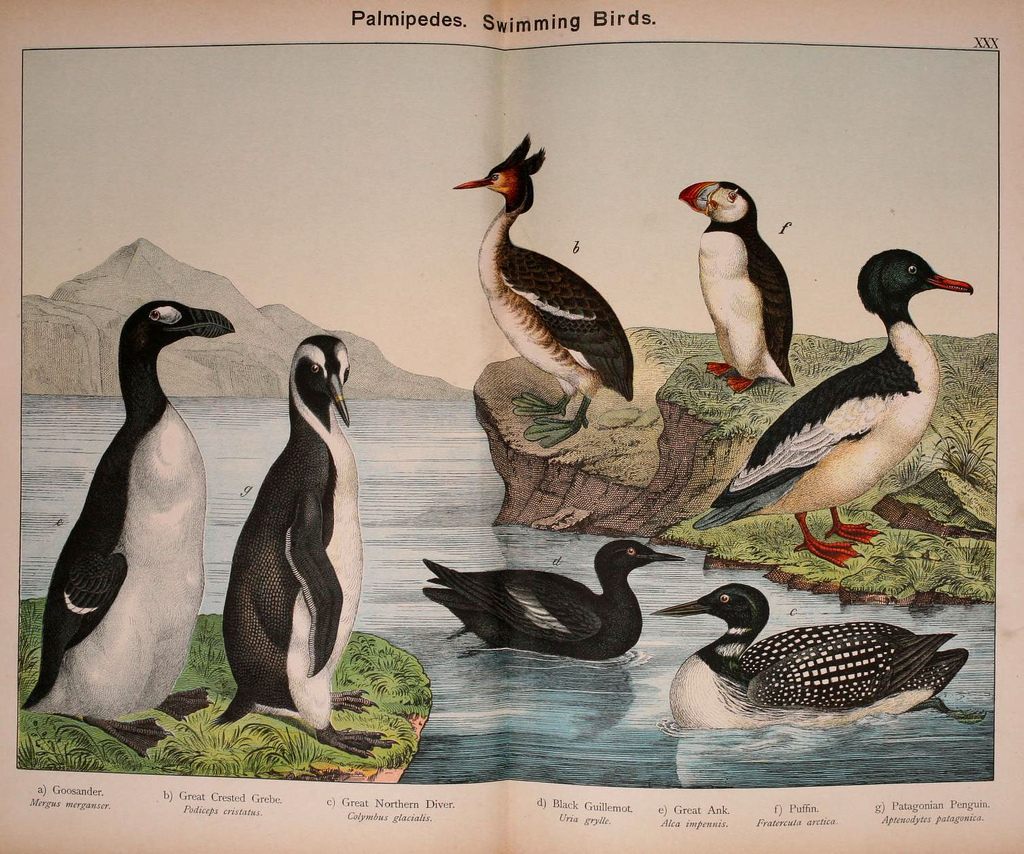

The glassy-eyed mounted specimens only hint at what was lost when we helped extinguish great auks. They look a little awkward, but in life they would have been striking, the northern hemisphere’s answer to penguins. Though the northern and southern flightless birds have a resemblance, they are not closely related. Penguins and auks are a case of convergent evolution, where two similar niches led two lines of evolution travel different paths to the same result. (Think of the body shapes of dolphins and sharks, or the wings of bats and ravens.) The name “penguin,” though, originally belonged to the great auk, the Pinguinus impennis. In Welsh, pen gwyn means “white head,” and it may be that the white spot on the great auk’s head inspired the name.

“We really could have had flightless birds in the northern hemisphere,” says Montevecchi. People already flock to islands around Newfoundland to see puffins and other seabirds, and to Antarctic waters to see penguins. “You can only imagine what we could do with islands with flightless birds on them,” Montevecchi says. “They capture people’s imagination.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook