A Cherished BBC Radio Show Asks Celebrities to Pick a Desert Island Survival Kit

On “Desert Island Discs,” guests choose one piece of music, one luxury item, and one book.

If the producer Simon Cowell were cast away on a desert island, he told the BBC in 2006, choosing a luxury item to while away the days with would be an easy task. “A mirror,” he told the English broadcaster Sue Lawley, who wondered aloud if he were joking. “It’s true,” he replied. “Because I’d miss me.” “Are you going to let us broadcast that?” she asked. “I don’t care,” said Cowell. “What, I’m on my own, no one else is around, I might as well have something, I’ll have a mirror.”

For 76 years, these kinds of extraordinary exchanges have taken place on a British radio show called Desert Island Discs, where famous, illustrious, or just plain interesting people are tasked with imagining themselves as island “castaways.” Every Sunday morning, over the course of an hour-long interview, these guests choose eight records to share with the public, as a kind of soundtrack to their lives. At the end at the program, they must choose just one piece of music—these days, often a pop song; when the show started, usually a longer piece of a classical music—to take to an unspecified desert island, along with a work of literature and a luxury item of their choosing. They are also given the Complete Works of Shakespeare and the Bible (or an equivalent religious text) as freebies.

The show plays each week on the BBC’s Radio 4, a primarily spoken-word channel that bookends drama, comedy, science, and history with snippets of news. For many Brits, it is part of the aural tapestry of being in the kitchen at home: the gurgle of an electric kettle, drizzle outside the window, and the quiet hum of Radio 4. Each week, around 3 million people will listen to Desert Island Discs, which has been hosted by the Scottish broadcaster Kirsty Young since 2006. Some do actively tune in, but many will simply wander into the kitchen at some point during the program and decide to keep on listening—depending on the guest.

The program was created in 1942 by its first presenter, Roy Plomley, whose interviews often dwelled on the specifics of life on the island, and whether his guests, like Margaret Thatcher in 1978, were any good at camping. For the entirety of its run, the show has opened to the strains of a sing-song orchestral valse, By the Sleepy Lagoon, by the composer Eric Coates, who himself appeared on the program in 1951. Herring gulls shriek over the top of the music, to give a desert island “feel.” When it was pointed out in the 1960s that they were native to the northern hemisphere, and would not have been found on a tropical island, they were briefly replaced with more authentic sooty terns. Listeners complained, and the gulls returned for good.

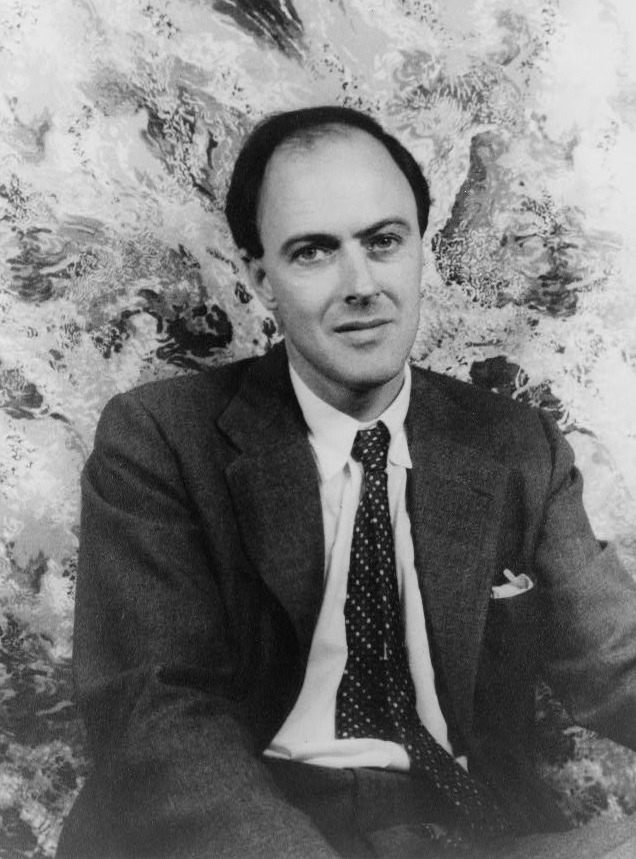

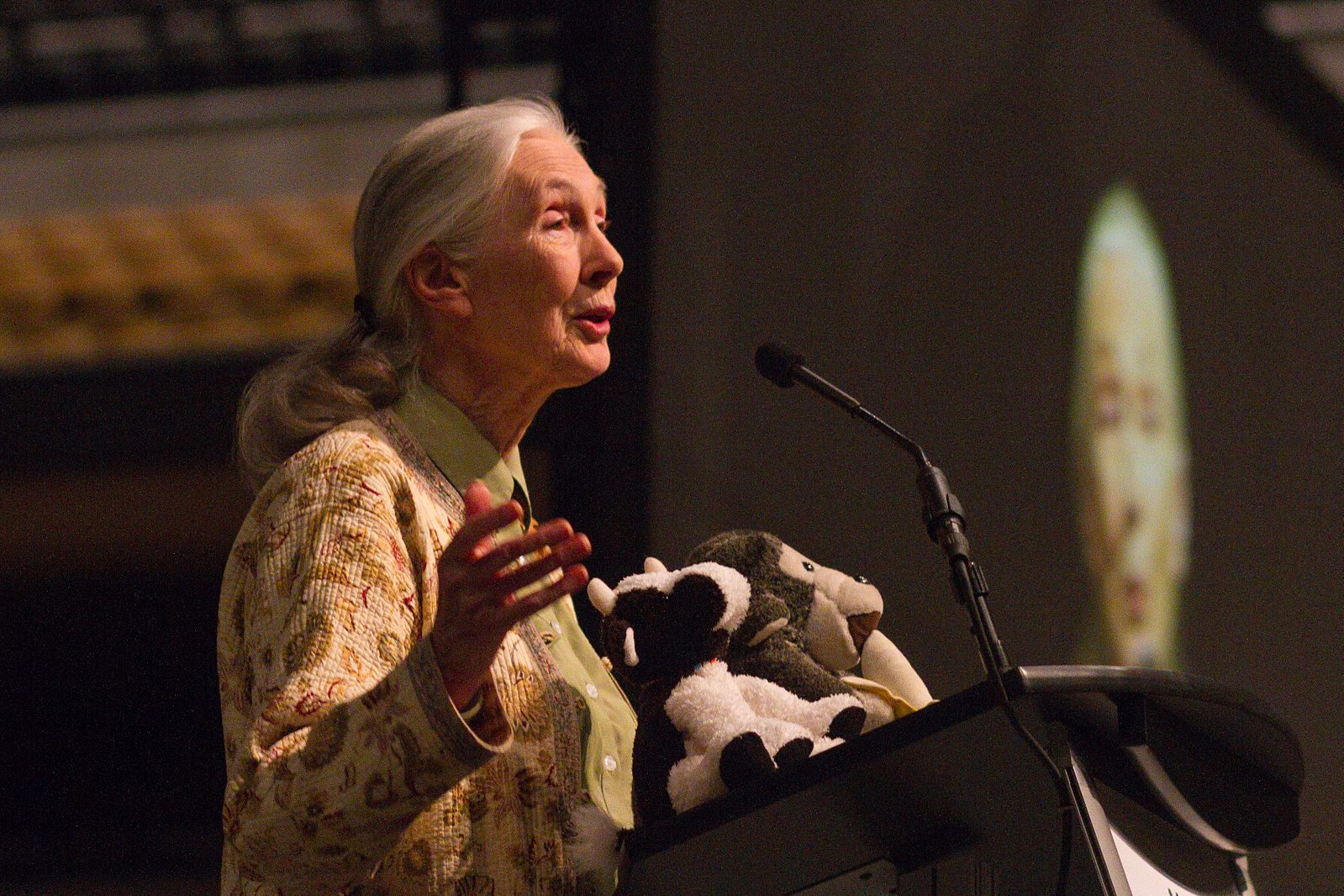

More than 3,000 people have appeared on the program in these nearly eight decades. Among the ‘D’s alone are Davids Attenborough (three times!), Walliams, Mitchell, and Beckham; Dames Judi Dench and Zaha Hadid; Dukes and Duchesses of Devonshire and Westminster. In the show’s back catalog are musicians, actors, authors, and doctors; politicians, pundits, designers, and tycoons. Some guests have mass appeal, like the actors Tom Hanks or George Clooney. Others have simply lived extraordinary lives, like the Wales-born vascular surgeon, David Nott. He described making life or death decisions in Aleppo and nearly broke down in tears as he told Young about returning home to his wife, after being in Syria.

Appearing on the show has become a point of pride. Speaking at the Cheltenham Literary Festival in 2012, the producer Leanne Buckle told the audience that celebrities often wrote in to the program, asking to appear on it. “I wrote a really kind letter saying we were pleased they liked the program,” she said of one anonymous letter-writer. “The person wrote back to say really I ought to reconsider my decision because they were very interesting. I wrote back again politely declining. Then their daughter wrote and said, ‘If my father has a heart attack it will be your fault!’”

But there are still a few hold-outs. At the same festival, Young described Elizabeth II as her dream guest. “There is quite a long list. It’s never going to happen, but Her Majesty would be wonderful.” The playwright Alan Bennett, who last appeared on the program in 1967, is high up on the list, she said, as was Rolling Stone Mick Jagger.*

For its audience, part of the pleasure of the show lies in choosing your own imaginary songs. Would you opt for your all-time favorites, or the ones that had really summed up your life, no matter how questionable? (An even greater pleasure, perhaps, is knowing that you probably won’t ever have to appear on the show, and reveal your musical tastes to the world.) Speaking on the show in 2006, the restaurant critic A. A. Gill said he’d been planning his list since he was a child, while the actor Patrick Stewart claimed to have carried round a list of his top eight song choices, on the off-chance he was asked to appear.

But listeners don’t necessarily tune in for the music choices. Instead, it’s the interviews which often draw people in, to reap moments of incredible personal candor from the guests. Sometimes, these come in the choice of a luxury item—a worrying number of people have asked for a blow-up doll. At other times, such moments arrive simply through beautiful, considered answers. Behind the scenes, Young and her producers will spend hours researching the lives of the people they’ll interview, so that the perfect, searching question, when it comes, is almost never an accident. She’ll prepare sartorially too, she told Radio Times, donning an open-neck shirt for Bill Gates and a sharp suit for Paul Weller. “And we had it on good authority that Morrissey drinks neat vodka, so we made sure we had a bottle,” Young told the magazine. “When my producer said, ‘Would you like some tea or coffee… or vodka?’ Morrissey said, ‘Vodka.’ I had one as well. I wasn’t going to have a cup of tea when Morrissey was having a vodka. I didn’t drink it, he did.”

At the end of the program, having chosen their eight records, guests must select just one song with which to spend eternity on a desert island. Sometimes, this is the hardest part—harder, even, than choosing the original eight, or engaging with Young’s courteous cross-examination. For the actress Judi Dench, it was near-impossible. “I will take…” she began. “Hm. I don’t want any of these. I don’t want to go to the island. I don’t want any of those records with me. What’ll I take?” She paused, startled by the question. “I’ll take… Sinatra. … What a nightmare.”

*Correction: The article originally referred to “Sir” Alan Bennett. We have removed the Sir, having learned that Bennett turned down a Commander of the British Empire honor in 1988 and rejected a knighthood in 1996.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook