The Lost Aria Rediscovered in Venice’s Ospedaletto After 250 Years

A fresco at the historic refuge leads a musicologist to a composition not heard for centuries—and the determined young women who once performed it.

This story was originally published on The Conversation. It appears here under a Creative Commons license.

Imagine Lady Gaga or Elton John teaching at an orphanage or homeless shelter, offering daily music lessons.

That’s what took place at Venice’s four Ospedali Grandi, which were charitable institutions that took in the needy—including orphaned and foundling girls—from the 16th century to the turn of the 19th century. Remarkably, all four Ospedali hired some of the greatest musicians and composers of the time, such as Antonio Vivaldi and Nicola Porpora, to provide the young women—known as the “putte”—with a superb music education.

In the summer of 2019, while in Venice on a research trip, I had the opportunity to visit the Ospedale di Santa Maria dei Derelitti, more commonly known as the Ospedaletto, or “Little Hospital,” because it was the smallest of the four Ospedali Grandi.

As a musicologist specializing in the music of early modern Venice, I was especially excited to visit one of the hidden gems of the city: the Ospedaletto’s music room, which was built in the mid-1770s.

I had heard about its beauty and perfect acoustics. So when a colleague and friend, classical singer Liesl Odenweller, suggested we go together, I was delighted. I also secretly hoped Liesl would feel inclined to sing in the space, so I could experience the pure acoustics of the room.

Little did I know that I would encounter music that hasn’t been performed in nearly 250 years.

As we entered the stunning music room, I was immediately struck by its elegance and relatively small size. In my mind, I had envisioned a large concert hall; instead, the space is intimate, ellipse-shaped and richly decorated.

Overshadowed by the more prominent Ospedale della Pietà, not much is known about the music-making that took place for centuries behind the walls of the Ospedaletto. But one of the greatest clues to its venerable history as a music school is literally on one of its walls.

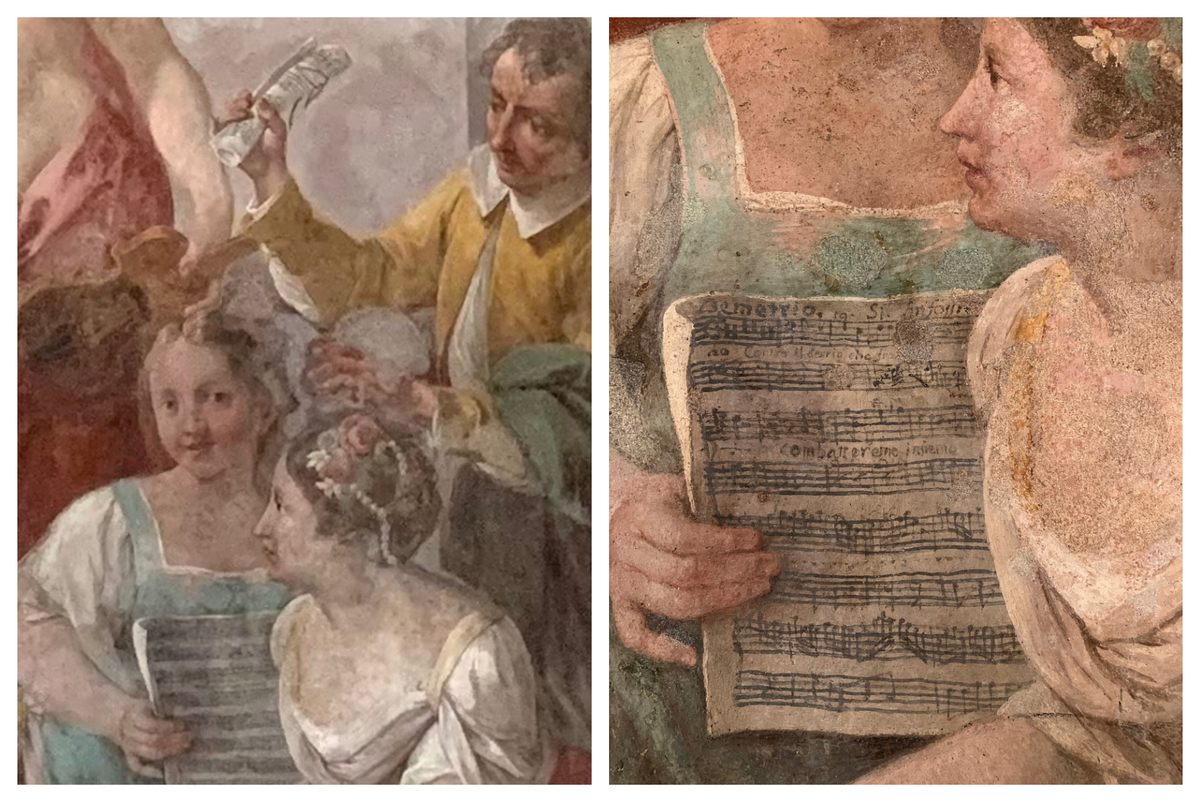

A fresco on the far wall of the room, painted in 1776-77 by Jacopo Guarana, depicts a group of female musicians—likely portraits of some of the putte—at the feet of Apollo, the Greek god of music. Some of them play string instruments; one, gazing toward the viewer, holds a page of sheet music.

Call it a professional quirk, but when I see a music score depicted in a painting, I have to get up close and try to read it. In this case, I was lucky: The music notation was quite legible, and the composer’s name was inscribed in the upper-right corner: “Sig. Anfossi.”

I took several photos of the fresco. I wanted to learn as much as I could about that piece of music painted on the wall.

The sound of Liesl’s singing snapped me out of my music detective mode. As I had hoped, her beautiful soprano voice filled the space with a tone so pure that it sounded almost ethereal. I turned around, but my friend was no longer in the room. Where was her singing coming from?

Liesl, it turns out, was perched in the singing gallery. With the permission of a clerk, she had climbed up to this partially hidden loft and was singing through a grille. It was here that the putte of the Ospedaletto performed in public concerts, their features partially obscured from the prying glances of the male listeners below.

Armed with those clues on the wall, I continued my research in the days following the visit to the Ospedaletto. I learned that the music by “Signor Anfossi” shown in the fresco was drawn from the opera “Antigono,” composed by Pasquale Anfossi (1727-97) on a libretto by Pietro Metastasio. The work premiered in Venice at the Teatro San Benedetto in 1773.

The text of the solo song—known in opera as an aria—is legible in the excerpt on the wall. It reads, “Contro il destin che freme, combatteremo insieme”—“Against quivering destiny, we shall battle together.”

Like many works from the 17th and 18th centuries, the entire opera is lost. I was determined to find out, however, if that particular aria had survived. Sometimes, the “hit tunes” of an opera were copied or printed separately and performed as arie staccate—arias that were “detached” from the rest of the work.

Luck was on my side: To my delight, I found a copy of the aria in a library in Montecassino, a small town southeast of Rome. Why was that particular excerpt chosen to be displayed so prominently on the wall?

Like other institutions in Venice, the Ospedaletto faced financial hardship in the 1770s. Evidence suggests that the putte of the Ospedaletto were likely involved in raising the funds for the decoration of the music room. The new hall enabled them to give performances for special guests and benefactors, which brought in substantial donations. Together with Pasquale Anfossi, who was their music teacher from 1773 to 1777, they rallied behind their beloved institution, saving it—at least temporarily—from financial destitution.

“Against quivering destiny, we shall battle together” may well have served as a rallying cry for the putte of the Ospedaletto, who literally “battled together” to preserve their splendid music conservatory.

Incidentally, the putte may also have wanted to honor their teacher, as Pasquale Anfossi, too, is portrayed in Guarana’s fresco, directly behind the young woman holding up his music.

One of the aspects I find most rewarding about the study of older music is the process of discovering a work that has been neglected and unheard for hundreds of years and bringing it back to modern audiences.

Inspired by the Ospedaletto’s music room, Liesl Odenweller and I have embarked on a collaborative project that brings back not only the aria on the wall but also other music from the institution that has gone unheard for centuries. Thanks to a generous grant from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation, the Venice Music Project— the ensemble Liesl co-founded in 2013—performed this music in a concert in Venice earlier this month.

The program included “Contro il destin” as well as other excerpts from “Antigono”—essentially, all that survives from that opera. In addition, we included works by Tommaso Traetta (1727-79) and Antonio Sacchini (1730-86) who, like Anfossi, taught the young women, in some cases launching their international music careers.

Because the music of the past was written in a notation that’s different from that used today, it’s necessary to translate and input every mark of the original score—notes, dynamics, and other expressive marks—into a music notation software to produce a modern score that can be easily read by today’s musicians.

By performing on period instruments and using a historically informed approach, the musicians of the Venice Music Project and I were excited to revive this remarkably beautiful and meaningful music. Its neglect is certainly not a reflection of its artistic quality, but rather likely the result of other composers, such as Vivaldi and Mozart, taking over the spotlight and overshadowing the works of other masters.

This music deserves to be heard—as does the story of the young women of the Ospedaletto.

Marica S. Tacconi is distinguished professor of musicology and art history at Penn State.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook