When Everyone Wanted to Be the Iceman

Before refrigeration, New York’s ice-delivery men inspired raunchy jokes.

There’s a tasteless wisecrack people sometimes make about kids with a different hair color than their father. “Does the mailman have red hair?” some jokester will inevitably ask. In the 1950s, when the local dairy made home deliveries, the same jokes circulated about the milkman. And before that? Well, in the latter part of the 1890s, it was the iceman who took the blame for leading women astray.

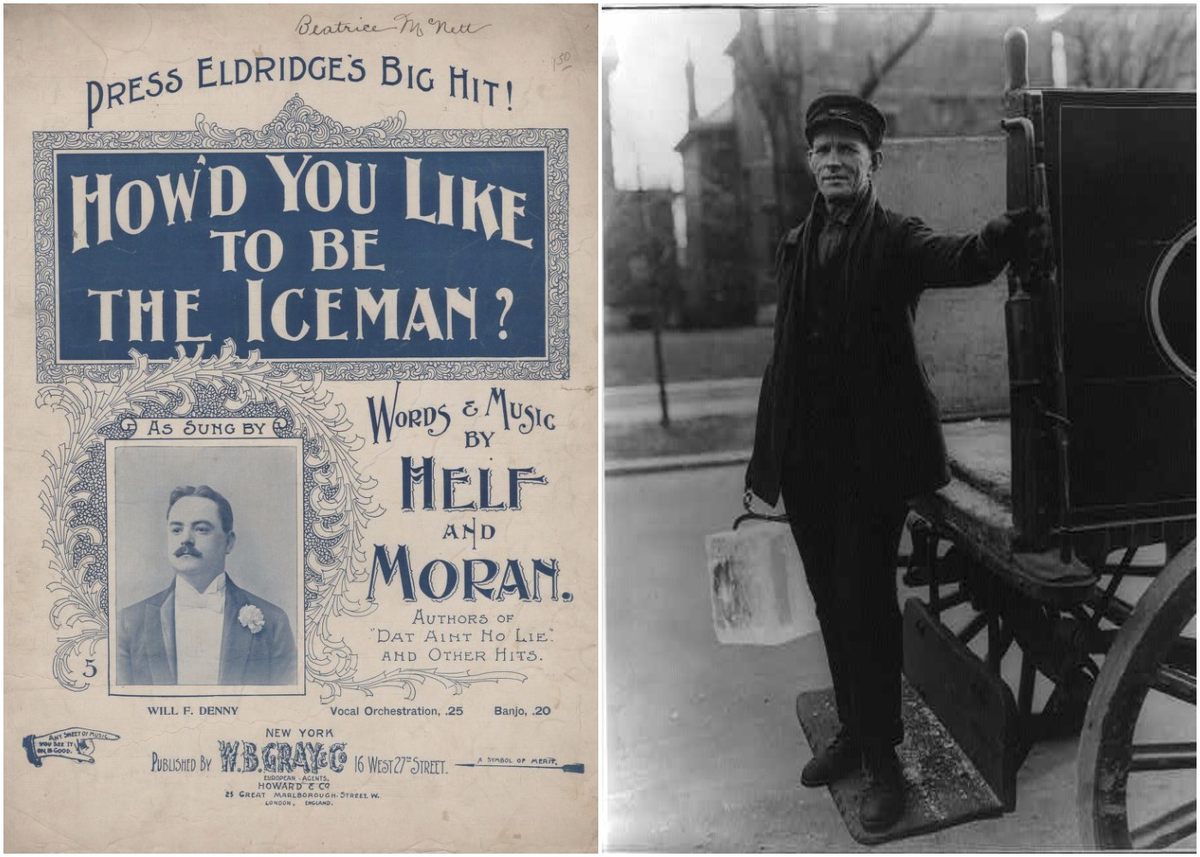

In fact, the idea of the ice-delivery man flirting with stay-at-home wives was such a trope that it inspired a hit song. Composer J. Fred Helf left Kentucky for New York in the 1890s to try his luck as a writer and seller of sheet music. Inspired by the city, he co-authored vaudeville-style comic songs such as “Please Mr. Conductor, Don’t Put Me Off the Train” and “Tillie Tootie the Coney Island Beauty.” In 1899, he scored his first big success with “How’d You Like to Be the Iceman?” It became a pop culture phenomenon—spawning answer songs, movie spin-offs, and merchandise. Soon every New Yorker and American knew the phrase “How’d You Like to Be the Iceman?”

Helf had captured the spirit of the times. Ice delivery was booming in the late 1800s, particularly in big cities, where fresh ice was a necessity. As New York and other urban areas grew, people lived further and further from the sources of their food. Ice kept dairy and meat products fresh, which improved and diversified urban diets and restaurant offerings as fresh fish, ice cream, and other foods became available. New recipes, such as icebox pie, capitalized on the ability to serve chilled dishes. And as cocktail culture was on the rise, ice was essential for cooling city dwellers’ drinks.

During the summer months, venues such as Carnegie Hall and Madison Square Garden fed several tons of ice per event into cooling systems that relied on a maze of ductwork, ice blocks, and fans. Even mortuaries relied on ice before electric refrigeration. Manhattan and Brooklyn alone melted their way through at least 1.3 million tons of ice per year—more than 25 percent of the entire country’s usage.

The majority of the city’s ice was harvested directly from lakes and ponds in the Hudson River Valley region, much of it from Rockland Lake, earning it the nickname “The Icehouse of New York City.” Using horses and plows, workers cut through the ice in grids, then sawed it by hand, floated thick blocks (known as “cakes”) to shore via man-made channels, and stored them in insulated icehouses. Men and horses could fall into the icy water and drown, but it was lucrative work. Thousands of men took their chances each winter.

All that ice called for a lot of icemen, and New York City had ‘em. Around 1,500 ice trucks made daily deliveries to businesses and homes. By the 1890s, all but the poorest residents had ice boxes—insulated cabinets made to hold a large block of ice with shelves for food and a drip pan underneath. In an era when men usually worked while wives kept house, it was the woman’s responsibility to alert the iceman to the household’s needs by placing a paper ticket in the window. Using a pair of large tongs, he would sling a cake of ice onto his burlap- or leather-covered shoulder, then haul the ice into the house or apartment.

An iceman had to be in good physical shape, which made his presence all the more concerning to husbands who were away. Unlike other delivery men, he had to come inside, and ensconcing ice in the box sometimes required chipping away at the block until it fit. It wasn’t unusual, after all that work, for the lady of the house to offer the ice man a drink or snack. It’s no wonder that he came to be perceived as a working-class lothario—sort of a 19th-century version of a buff pool boy.

“How’d You Like to Be the Iceman?” capitalized on the idea that icemen had it made. In the opening verse, the narrator admires a brownstone mansion and asks the servant if Mr. Vanderbilt is in. “I thought it the house of a millionaire,” the song continues, “but he told me the iceman resided there.” Subsequent verses describe the iceman trading ice for kisses at customers’ homes and enjoying free drinks at the cafe. (These are referred to as “tin-roof cocktails,” capitalizing on a joke with a double meaning about tin-roof cocktails being “on the house.”)

There was some truth to the idea. At least one ice-wagon driver was arrested for intoxication and, in court, blamed all the whiskey, beer, and wine that women supplied him along his route. (The title of the newspaper report, of course, was “How’d You Like to Be the Iceman?”) But the majority of icemen lived far less adventurous lives, and one lamented to a reporter that most customers just haggled over prices or called him a thief.

The public, though, relished the fantasy of an iceman rolling in dollars and dames. It was fueled in no small part by Helf’s song, which burned up vaudeville stages and inspired at least two popular recordings, spoof versions, and one clapback in the form of “All She Gets from the Iceman is Ice.” Had there been a Billboard Hot 100 for Edison wax cylinders, “How’d You Like to Be the Iceman?” would have topped it. Soon the title became a catchphrase printed on everything from saucy newsstand postcards to novelty lapel pins. A coin-in-the-slot peep show version depicted—what else?—an iceman kissing a customer while she pours him a drink.

The iceman jokes declined with the industry itself. Mechanically produced ice, along with concerns about increasingly polluted rivers, diluted the Hudson Valley ice business. After President Roosevelt’s Rural Electrification Act of 1936 brought electricity to even the most remote farmhouses, demand for natural ice dropped off almost completely. Entrepreneurs repurposed the surviving icehouses along the Hudson River into mushroom farms. By 1950, more than 90% of homes had an electric refrigerator, and America entered the era of the TV dinner. The New York City iceman was out of a job.

The trope endures a bit today, but now it’s the cable guy or the pizza-delivery man that takes the ribbing. The next time you hear one of these throwback jokes, remember that it hearkens back to a time when cocktails had names like Tin-Roof, women named “Tillie” were hot stuff at Coney Island, and everybody wanted to be the iceman.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook