Why Are So Many Different Drinks Called Horchata?

An ancient medical elixir is the ancestor of a family of drinks.

Mexican horchata is the agua fresca that dreams are made of. While sweet and slightly creamy, it usually isn’t dairy-derived. Instead, it’s made by soaking white rice in water and cinnamon for several hours, straining, and adding sugar. Vaguely reminiscent of a delicate rice pudding, there’s nothing more refreshing than a cold cup of horchata on a hot summer day.

But long ago, horchata was more than just a refreshment. While the Mexican version of the drink first appeared in the 16th century, its roots date back to an ancient Roman medical elixir made from barley. In fact, the word horchata comes from the Latin hordeum (barley) and hordeata (drink made with barley). From its role as medicine in antiquity, the beverage took a circuitous route across Europe and across the Atlantic to Latin America. Along the way, horchata became a whole family of drinks made from various grains, nuts, and seeds.

Ancient doctors thought that barley, the oldest cultivated cereal in the Near East and Europe, possessed cooling properties. Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician who famously said, “let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food,” recommended barley water for the healthy and sick alike. But while it was hydrating and nutrient-rich, the ancient drink was fairly tasteless. Prepared by boiling barley in water, it had to be flavored with honey and fresh herbs.

Cato the Elder, the Roman statesman, orator, and author, recommended drinking barley water on a hot day in his 2nd century BC work De Agri Cultura (On Agriculture). He also advised mothers to feed it to their fussy babies as a soothing aliment. Later, the Roman physician Galen praised barley water as “nourishing” in his De alimentorum facultatibus (On the Properties of Foodstuffs). By the 6th century, Byzantine physician Anthimus prescribed a barley and water concoction to lower his patients’ fevers.

Ancient texts and the recipes they contained spread throughout France and England during the Middle Ages. In France, an early recipe for barley water appears in 1393’s Le Ménagier de Paris (The Parisian Household Book), which offers tips on running a household, recipes, and medical advice. The instructions call to “take water and boil it” before adding barley, licorice or figs, boiling again, and straining into “goblets with a large amount of rock sugar.” In a nod to its medicinal roots, the author recommended the beverage for invalids. A variation called orgemonde (from orge mondé, or hulled barley) contained ground almonds, and in England, herbs and raisins were a common addition.

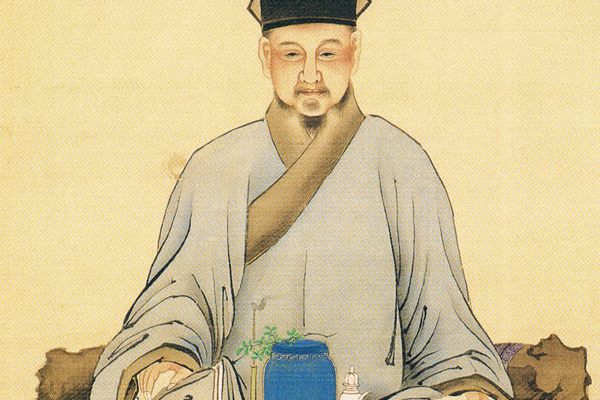

In Spain, the drink pivoted from both its medicinal and barley roots when the Moors—who ruled parts of the country from 711 to 1492—introduced the chufa, or tiger nut, from North Africa. (The chufa, a tuber, is called a nut simply because it looks like a hazelnut.) Historical Persian and Arabic documents mention the chufa as energy-giving and healthy. Medieval physicians and botanists such as Ibn Bassal cited the chufa plant in their works on medicine and agriculture. Soon, this nut-like tuber was used to make a new refreshing beverage: horchata de chufa.

A popular legend proclaims that King James I of Spain coined the word horchata, when a young peasant girl served it to him on a hot 13th-century day. After taking his first refreshing sip, Aragon exclaimed in Valencian dialect, “Aixó es or, xata!” (This is gold, pretty girl!) While only a legend, a first recipe featuring something like the contemporary beverage is from the 1324 Catalonian manuscript Llibre e Sent Soví, where it appears as llet de xufes, or chufa milk. The mixture of soaked and ground tiger nuts, sweetened with sugar and flavored with cinnamon and lemon rind, became a common drink among Hispano-Arabs in Spain.

Simultaneously, as part of the diffusion of Islamic culture, horchata wended its way to West Africa. Refreshing and invigorating on a hot Nigerian day, kunnu aya is yet another version of horchata, but one of the rare versions not to bear the name as well. In the Hausa language, kunnu refers to any milky drink made from cereal, grains, or nuts, and aya is the tiger nut.

But horchata couldn’t be contained to the Old World. In the 16th century, Spanish conquistadors brought rice, sugarcane, and cinnamon to Mexico, but they didn’t bring tiger nuts. A new drink, made with rice instead, perhaps offered the conquerors a taste of home. While Mexican horchata is traditionally made with rice, cinnamon, and sugar, some variations feature dried cantaloupe seeds, coconut, and even oatmeal. In northern Mexico, there’s a version still made with barley called horchata de cebada: literally “a drink made with barley of barley.”

After horchata took hold in Mexico, it begat countless descendants across Latin America. Puerto Rican and Venezuelan horchatas showcase sesame seeds. The Salvadoran incarnation is made with ground seeds of the morro, a green, hard-shelled fruit that is part of the calabash family. Horchata makers remove the morro’s lentil-shaped seeds from the fruit’s pulp and dry it in the sun, before grinding them up for horchata. In addition to cinnamon, horchata de morro is spiced with nutmeg, coriander seeds, and allspice.

Ecuador’s horchata lojana is quite different. Named after Loja, the province that popularized it, the South American staple is bright pink. No nuts or grains are used. Instead, it is an infusion of 18 different herbs and flowers. Among them are rose, geranium, carnation, borage, and flax seeds. Escancel, or bloodleaf, and red amaranth give it vibrant color. Since many of the plants used are medicinal, the drink is consumed for its therapeutic benefits, much like its ancient ancestor.

But in England, the age-old drink of barley water was showing its age. In the 18th century, barley was dropped altogether for a drink called orgeat, which consisted of almonds instead. Sweetened with sugar, flavored with orange flower water, and served cold much like one would serve lemonade today, orgeat became a popular summertime refreshment for Regency, Georgian, and early Victorian-Era ladies. By the 20th century, barley water itself was considered stuffy and old-fashioned. (In the children’s book series Mary Poppins by Australian-English writer P.L. Travers, the children stipulate that their nanny must “never smell of barley water.”) There are some holdouts, though. Since the 1930s, Robinsons Lemon Barley Water has been the official drink at Wimbledon.

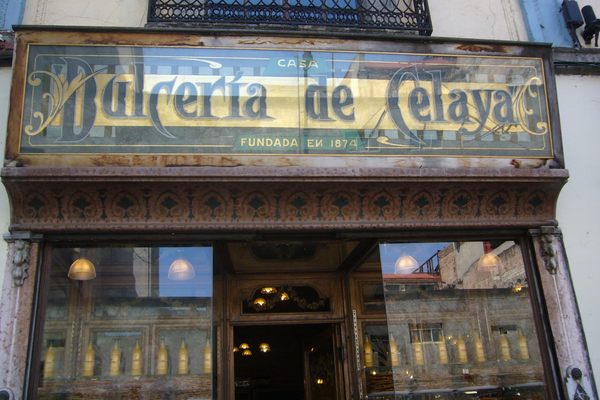

Most modern horchatas share little with their ancestors, flavor-wise, yet they are culinary and etymological cousins. Orgeat has become a sweet syrup flavored with almonds, used primarily in cocktails. And in Valencia, horchaterías still abound. Some, like Horchatería Santa Catalina, have been in business for over two centuries. While recipes vary from one horchatería to the next, none stray too far from the original 14th-century formula.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook