How a Fruit Basket From Mao Made China Mad for Mangoes

Regifting the fruit created a potent political symbol.

In August of 1968, China was suddenly gripped by a mania for mangoes. The fruit was praised in poems, worshipped on altars, and toured across the country like a celebrity. People posed alongside mangoes in portraits, poured tea into mango mugs, and took drags from MangGuo cigarettes. In Guizhou, thousands of peasants fought over a black-and-white mango picture. Ironically, most of the fruit’s fanatics had never tasted one. In fact, just months earlier, the mango had been virtually unknown.

The mango cult developed amid the tumult and terror of Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution, a decade-long crusade to purge the communist country of all remnants of capitalist thought and traditional Chinese culture. Mao’s credibility had been damaged by The Great Leap Forward—a series of agricultural and industrial reforms that led to famine and an estimated 45 million deaths. To reassert his authority and weed out political rivals, he called on Chinese youth to root out “capitalist roaders” and traces of the so-called feudal past.

The mission was eagerly embraced by millions of students, who were called Red Guards. Sporting military fatigues and red armbands, the teenage troops destroyed cultural relics, attacked people wearing “bourgeois” clothing, and slaughtered animals associated with the old, imperial regime. Suspected class enemies were publicly humiliated, beaten, and even killed.

“I saw so many people die because of the Cultural Revolution. People died right in front of me,” says Hongtu Zhang, an artist who lived through the Cultural Revolution. “I saw students following Mao’s ideas pile Chinese and Western books into a big hill and just burn it. It was not a Cultural Revolution, it was a culture being destroyed.”

Bonded only by their shared loyalty to Mao, the Red Guards quickly splintered into feuding factions and plunged the country into anarchic violence. After two years of bloodshed, Mao decided to restore order and reign in the rabid Red Guards.

On July 27, 1968, Mao ordered 30,000 factory workers to occupy Qinghua University in Beijing, which had devolved into a battleground between two student militias. Although the workers outnumbered the 400 or so students, they were grossly unprepared. Armed only with pictures of Mao, the workers faced a barrage of bricks, spears, sulfuric acid, and homemade bombs. They suffered casualties and sustained hundreds of serious injuries. But, with the assistance of the People’s Liberation Army, they prevailed.

As a token of his gratitude, Mao sent the workers stationed at Qinghua a case of mangoes, which he’d received from Pakistan’s foreign minister. The gift was accompanied by a message that declared the workers were now in charge of the revolution.

“Mao didn’t often give presents, so it was seen as a powerful gesture in support of the workers,” explains Dr. Alfreda Murck, a Chinese art historian and co-curator of the Mao’s Golden Mangoes and the Cultural Revolution exhibition at The Museum Rietberg.

“Few [people] had even heard the word [‘mango’], let alone seen one,” recalled Wang Xiaoping in Mao’s Golden Mango and the Cultural Revolution. “To receive such a rare and exotic thing filled people with a surge of excitement.”

“The workers decided not to eat them. They stayed up through the night looking at the mangoes, stroking them, and sniffing them,” says Murck. “The workers did not have any clue what they were, but because the mangoes were a gift from Mao, they were in awe of them.”

Over the next few days, military representatives delivered the mangoes to model factories, where workers attempted to preserve the precious fruit. At the Beijing People’s Printing Agency, workers placed their mango in a jar of formaldehyde, which eventually turned black and withered like an oversized raisin. At the Beijing Textile Factory, workers sealed their sacred gift in wax, but after a few days, it began to rot. In response, they carefully peeled the mango and boiled its pulpy flesh in a large pot of water. Afterwards, the factory held a Eucharist-like service where everyone drank a spoonful of the precious elixir.

China has a rich repertoire of food symbols, which lent the mangoes additional layers of meaning and significance. The foreign fruit was compared to the Mushrooms of Immortality and the Longevity Peach from Chinese mythology. Thus, Mao’s gift was interpreted as an act of selflessness, in which he sacrificed his own longevity for the workers.

Workers weren’t the only ones with mango madness. The fruit garnered widespread enthusiasm, much of which was based on the belief that the chaos of the Cultural Revolution had finally come to an end.

“There was this perception that Mao had stepped in to end the specific violence between the Red Guard factions on the Qinghua campus and the general violence of the Cultural Revolution,” says Murck.

In reality, Mao’s motives were far less noble. “Mao didn’t like fruit and didn’t want to eat these messy mangoes,” says Murck. “It was totally unexpected that they would be greeted with such awe and enthusiasm. It was a gift to the propaganda department.”

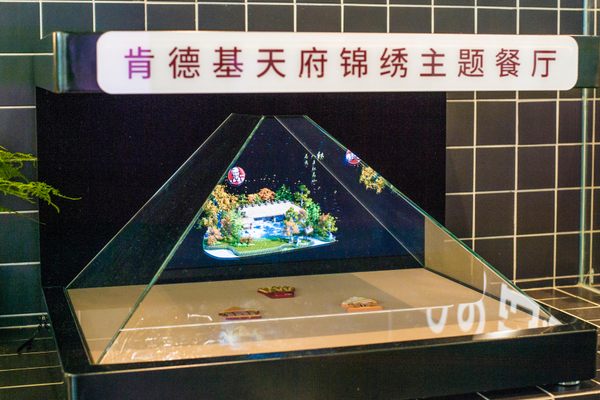

Indeed, the Party quickly adopted the fruit as a symbol of the transition of power from the Red Guards to the working class. Mango imagery was plastered on propaganda posters, often accompanied by the new slogan “the working class must lead in all things.” Gigantic papier-mâché mangoes decorated floats at the National Day Parade and wax replicas enshrined in glass vitrines were distributed as merit awards. Facsimiles were also publicly exhibited across China. No expense was spared in the mangoes’ grand tour: They traveled by private planes, special trains, and a fleet of custom “mango trucks.”

While the mango inspired genuine joy, there was a coercive undercurrent to the mass displays. Attendance at the mango exhibitions, parades, and celebrations was often mandatory. In the middle of the winter, oilfield workers in Daqing were forced into unheated buses in negative-22 degrees Fahrenheit and taken to a local mango exhibition.

“I don’t know how many people worshipped the mango from their heart,” says Zhang. “It was a simple way for people to show loyalty to Chairman Mao and protect themselves. If you didn’t pretend, you wouldn’t just be criticized by other people, you would die.”

The consequences of disrespect were dire. According to Wang, one of her colleagues was “admonished by senior workers for not holding the fruit securely, which was a sign of disrespect to the Great Leader.” In a 2007 essay, Murck recounts a fatal episode in Sichuan Province, where a man was dragged through the streets and executed for comparing mangoes with sweet potatoes.

A year and a half later, China’s mango fever broke. Once the anti-Red Guard policy was firmly in place, the mango disappeared from official propaganda. The mango replicas, devoid of their sacrosanct status, were used to wax thread and burned for light during power outages.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook