This Is the Most Detailed Map of Antarctica Ever Made

Scientists compiled decades of data to reveal the continent hiding beneath millions of miles of ice.

If you had to, how would you remove 6.5 million cubic miles of ice from Antarctica? In truth, you have two options: On one hand, you could dramatically accelerate the warming of the world to turn Earth’s southernmost continent into a parched realm. On the other, you could spend several decades zipping across it with planes, Ski-Doos, and people armed with some extremely cool pieces of technology. Fortunately, when a group of scientists set out to answer this question, they chose the second option—in part to understand what might happen in the event that climate change leads to the first one.

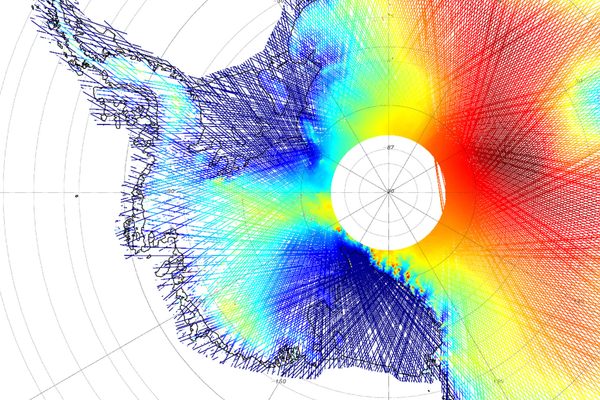

In March, an international team of scientists led by the British Antarctic Survey published the highest-resolution map of the geologic underworld of Antarctica ever made. It may be familiar to us as a frozen landscape, but that ice wasn’t always around. In fact, the ice is the relatively new frosting atop an ancient rocky foundation that’s been sitting there for hundreds of millions, if not billions, of years. Now anyone can peek at it, thanks to technology that saw right through all that ice.

The map reveals Antarctica’s bedrock with a startling clarity. Deep, scar-like canyons meander around colossal mountain ranges. Some low-lying patches sit so far down that they’re actually below the present-day sea level. The ice atop one particular crevasse is almost three miles thick—that’s 15 times the height of the Shard in London, one of Europe’s tallest skyscrapers.

But this is about more than making a visually striking map. Plenty of Antarctica’s ice is melting thanks to humanity’s unyielding predilection for fossil fuels. Knowing where the ice is thin and vulnerable, and being able to see where its meltwater will flow into the ocean, clues glaciologists and climate scientists into how Earth’s largest collection of (melting) ice will change sea levels across the world.

Before I became a science journalist, I was a volcanologist, so I’m used to seeing maps that illuminate the mysterious, abyssal parts of the planet. I’ve glimpsed at depictions of Earth’s labyrinthine crust filled with reservoirs of incandescent magma; I’ve seen illustrations of colossal plumes of rock flowing and rising through the strange mantle below. These aren’t just vague sketches, but increasingly detailed paintings. They come about not through the power of imagination, but the power of geophysics. Using things like seismic waves—which pass through and bounce about in solid rock—scientists can get a sense of what’s going on where we can’t see it, down deep below Earth’s surface.

The deeper you go, the lower the resolution gets. The seismic waves that bounce back contain information about their journeys, but much of that is open to interpretation. So when I see something like the British Antarctic Survey’s new map of the Antarctic bedrock, I can’t help but feel gleeful—as it happens, it’s a lot easier to peer through ice than it is to see through rock.

That’s not to say that creating this Antarctic map was easy. Far from it. A clue can be found in its name, “Bedmap3,” which signifies that it’s the third version of this map. The first version, created in the early 2000s, was made using half a decade of surveys that looked at the thickness of Antarctica’s ice. The second iteration, published a decade later, used a suite of more modern surveying methods to improve the original’s resolution and depth. And now, in 2025, we have the third version, which uses even more refined techniques to add plenty of three-dimensional information atop the previous one.

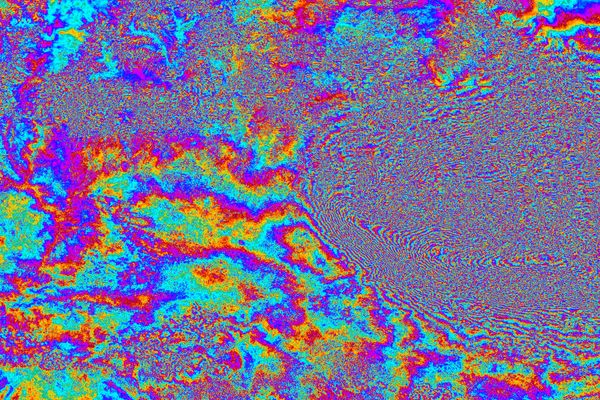

The researchers behind Bedmap3 have almost lost count of all the different methods scientists have used to measure the shape of the Antarctic ice, and to peer through it. To map out the ice’s surface features, scientists have used planes and satellites to fire lasers at the ice, then waited to see how long it takes for those lasers to return to the source. That can be used to determine a distance. Do that enough times, and you can make a very precise topographic map of the gelid continent. This has been complemented by something called optical imaging analysis—a fancy way of saying a scientist manually interprets satellite photographs to plot out the ice’s peaks and troughs.

Most of the fresh data that went into making Bedmap3 comes courtesy of ice-penetrating radar, which does exactly what you think it does: it fires radio waves through the ice, which hit the rocky foundations before bouncing back to receivers at the surface. This reveals the silhouette of the geologic land hidden below, as well as the thickness of the ice. This technique, also known as radio echo sounding (RES), was mainly conducted using planes. But additional RES surveying was carried out using motorized vehicles like snowmobiles and, reportedly, some dog-pulled sleds.

But other instruments were also deployed, including ones designed to measure the local gravity fields. This method, known as gravimetry, can reveal if there is a concentration of mass below your feet (say, from a mountain, which creates more of a gravitational pull) or a lack of mass (from a valley, for example). During some of the recent fieldwork, explosives were also used. Tiny detonations atop the ice generated seismic waves, like artificial earthquakes; those waves ricocheted through the ice, hit the bedrock, and eventually pinged back toward detectors on the surface. Scientists used this data to create a seismic map of the ice and of the roof of the underlying bedrock, like how geophysicists use (both natural and artificial) earthquakes to peep inside Earth’s geologic innards.

Altogether, the team collected a staggering 82 million individual points of data, revealing the benighted depths below that colossal sheet of ice in remarkable detail—from the South Pole to East Antarctica, the arched, jagged Antarctic Peninsula, and along the gnarly Transantarctic Mountains. The map lets us perceive the continent as it was about 35 million years ago. Back then, it would have been free of ice sheets and instead speckled with patches of tundra and swaths of lush coniferous forests. Now all that land is covered by 6.5 million cubic miles of ice.

If all that ice were to melt today, it would raise the global sea level by almost 200 feet—an apocalyptic scenario that would see a plethora of islands, as well as countless coastal (or low-lying) cities across the world vanish beneath the waves. Cairo, New York City, Buenos Aires, London, Venice, Hong Kong, and Sydney would all become real-life versions of Atlantis. Fortunately, that’s not going to happen all at once, but much of this ice is melting under the weight of anthropogenic climate change. Bedmap3 also reveals that parts of Antarctica are more severely imperiled than previously thought. For example, scientists have spied several rocky channels underneath the edges of the continent—these inlets permit warm water from the ocean to flow into chunks of thawing ice that sit inconveniently below sea level.

Climate change is, of course, bad news for the planet. Although scientists have a solid idea of how it will develop in the near future, fine-tuning their calculations is of vital importance. Sophisticated computer models designed to work out how all of Earth’s systems—the atmosphere, the oceans, the continents, the biosphere, humanity, and so on—are connected need to be fed the very best data on each individual system to be as accurate as possible. Bedmap3 is key to understanding how one system, the most elephantine piece of ice on the planet, is reacting and contributing to the warming world.

It just so happens that this map is also an aesthetic marvel, a painterly vision of a long-lost version of Earth that no human has ever seen. It was created by science, sure. But the end result is a little magical too.

Robin George Andrews is a doctor of volcanoes, an award-winning freelance science journalist, and the author of two books: Super Volcanoes: What They Reveal About Earth and the Worlds Beyond (2021) and How to Kill an Asteroid: The Absurd True Story of the Scientists Defending the Planet (2024).

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook