To Defy the United States, Fidel Castro Built the World’s Greatest Ice Cream Parlor

The socialist establishment, which is still slinging scoops, seated 1,000 customers.

That was a problem, because Castro was obsessed with ice cream. When he was still a young revolutionary in the jungle, a wealthy supporter, Celia Sánchez, sent him an ice-cream cake via mule for his birthday. When the rebellion succeeded, he established himself at the Havana Libre Hotel, where he habitually enjoyed the cafeteria’s milkshakes. In “A Personal Portrait of Fidel,” novelist Gabriel Garcia Marquez described Castro polishing off 18 scoops after Sunday lunch. His affection for ice cream was such that the CIA attempted to poison his milkshake. “That was the closest the CIA got to assassinating Fidel,” a retired state security general told Reuters in 2007.

But when the United States announced a total embargo in 1962, cutting Cuba off from the American dairy market (along with every other U.S. export), Castro found himself the leader of a milk-free island that was too warm for dairy cows. Undaunted, he demanded, in 1966, the construction of the greatest ice cream parlor the world had ever seen. Visitors to Havana can still eat there today.

Castro put the project in the capable hands of Sánchez. The daughter of a wealthy doctor, she had provided supplies to Castro and Che Guevara, eventually joining the young rebels in the jungle and in combat. When Castro came to power, she became his closest aide and an essential member of the socialist government. Opening a cathedral-like ice cream parlor was not the only odd assignment in her sprawling political portfolio: In the wake of cigar makers fleeing Cuba, she took charge of setting up factories to produce Castro’s favorite cigar.

In line with the Cuban Revolution’s wide-eyed optimism, Sánchez and Castro decided to build and open the parlor within six months. Sánchez, meeting with architect Mario Girona, asked him to design an ice cream factory and parlor that could serve 1,000 people. “At one time?” he recalled asking, shocked by the size and scope. The establishment was named after Sánchez’s favorite ballet, Coppelia, and staffed by waifish women who looked like ballerinas. The logo was a pair of plump legs in a tutu.

When Sánchez met with Girona, Cuba was not completely without cows—Castro had spent the four years since the embargo designing a dairy industry from scratch. Supplying Coppelia and the rest of Cuba with local milk became an obsession equal to his passion for ice cream.

Cuba had zebu cattle, a hardy breed that is found in many tropical countries, but provides little milk. So Castro imported Holstein cows—the iconic black and white variety—from Canada. But even when housed in air-conditioned barns, they failed to thrive in Cuba.

“A third of the Canadian cows died in a matter of weeks,” writes Mark Kurlansky in Milk! A 10,000-Year Food Fracas, “leading Castro to pronounce they would have to invent a new Cuban breed, ‘the Tropical Holstein.’”

Castro believed that developing Cuba’s own dairy industry was worth the expense. “We have known the bitterness of having to depend on others,” Castro said in a speech, alluding to the American embargo, “and how this can be turned into a weapon against us.” He was motivated, too, by a desire to show socialism’s superiority. In another speech, he explained that while capitalism made better products at first, it eventually produced lower quality goods than socialism. Coppelia was his main example.

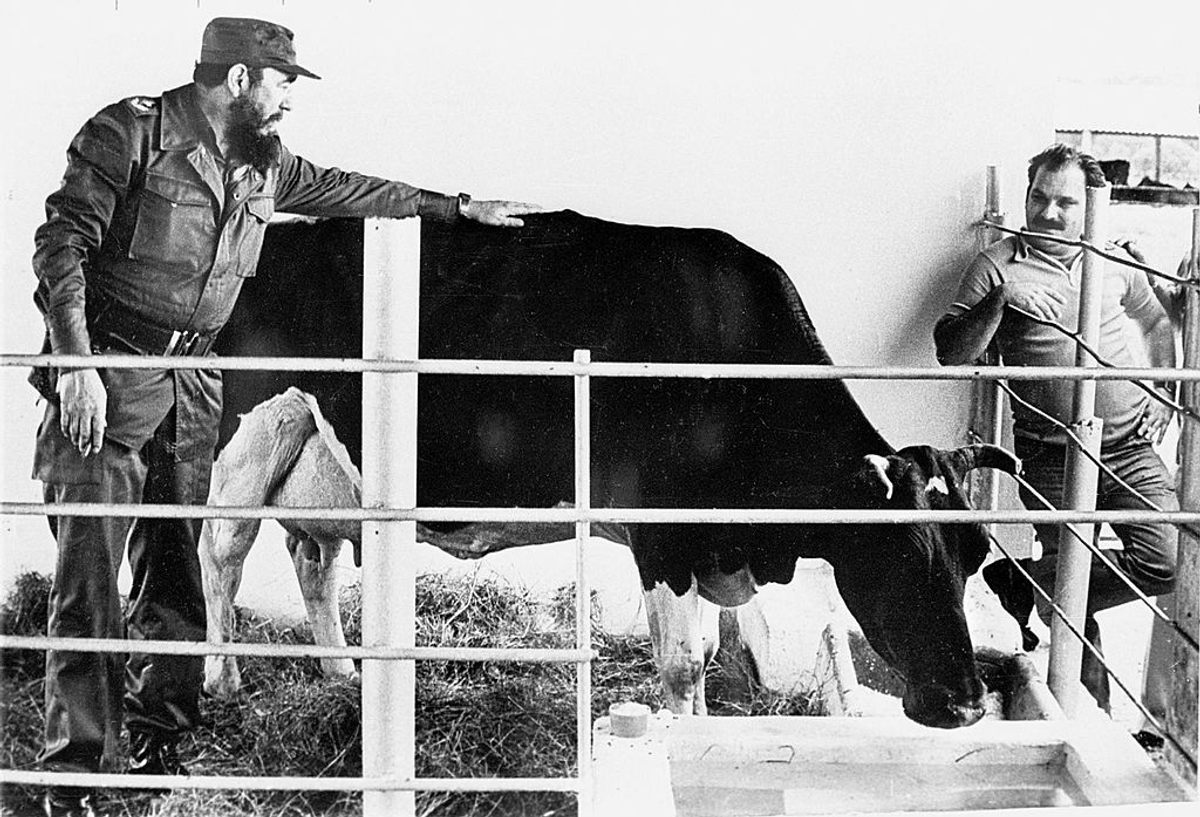

In the 1960s, Americans and Russians valorized their astronauts. Cuba had Coppelia and its cows. Specifically, it had Ubre Blanca, by far the best of Castro’s Tropical Holsteins. Castro loved to show her to journalists and foreign dignitaries, and Cuba’s press reported her every exploit. Kept in a guarded, air-conditioned stable and constantly monitored by specialists, she produced, in one record-setting day, four times as much milk as the average cow, smashing the previous record set by an American bovine, Arleen. For Castro, who peppered his hours-long speeches with statistics about the triumphs of Cuba’s socialist economy, it must have felt like when Russia put a man in space before the Americans. Dairy was his space race.

But the combination of Castro’s forceful personality and micromanagement often led to poor outcomes—in one case, Castro ordered underlings to cross two cow breeds that every animal husbandry student knew would not produce successful offspring. Ubre Blanca was a rare exception, and Castro’s dairy industry faltered.

While Castro’s dairy dreams died, Sánchez still delivered with Coppelia. In One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution, writer and photographer Nancy Stout describes the ice cream parlor as “one of Celia and Fidel’s greatest projects.” The domed, two-story ice cream palace, she writes, was a “dazzling, spun-sugar white.” Open to the air, the palatial structure had stained glass and seating for 1,000.

“Before the revolution, the Cuban people loved Howard Johnson’s ice cream,” Castro told a visiting journalist shortly after Coppelia opened, referring to the iconic American brand. “This is our way of showing we can do everything better than the Americans.” And, indeed, even visitors from the U.S. conceded that Coppelia was likely serving the world’s best ice cream. Coppelia had dozens of flavors and sent them, packed in dry ice, to dignitaries, international food festivals, and friends of the revolution, such as Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh.

Castro never achieved his dream of dairy self-sufficiency, and, at times, that has meant that the poor economy and economic embargo led to Coppelia having fewer, or lower-quality offerings. But to a surprising extent, his vision has endured.

Coppelia remains a singular place to enjoy ice cream. The line to order snakes outside each day, just as it has for decades, reflecting both the parlor’s popularity and the shortages that afflict Cuba. In One Day in December, Stout describes Coppelia as the type of place where you go on a first date or take your mother.

One of the few elements of the original Coppelia that didn’t last were the delicate servers, who couldn’t keep up with the heavy demands of the ice cream palace. To this day, the most popular order is an ensalada—a five-scoop sundae—and, in a very Castro move, it’s common to order three.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook