All Aboard the World’s First Floating Dairy Farm

More sustainable food production may call for plopping cows on the water.

The waters of the Nieuwe Maas snake through the city of Rotterdam, giving way to sandy beaches, bustling harbors, and, soon, a small herd of floating cows. It may sound like science fiction, but the world’s first floating dairy farm, the brainchild of Dutch property development company Beladon, is well on its way to becoming a reality.

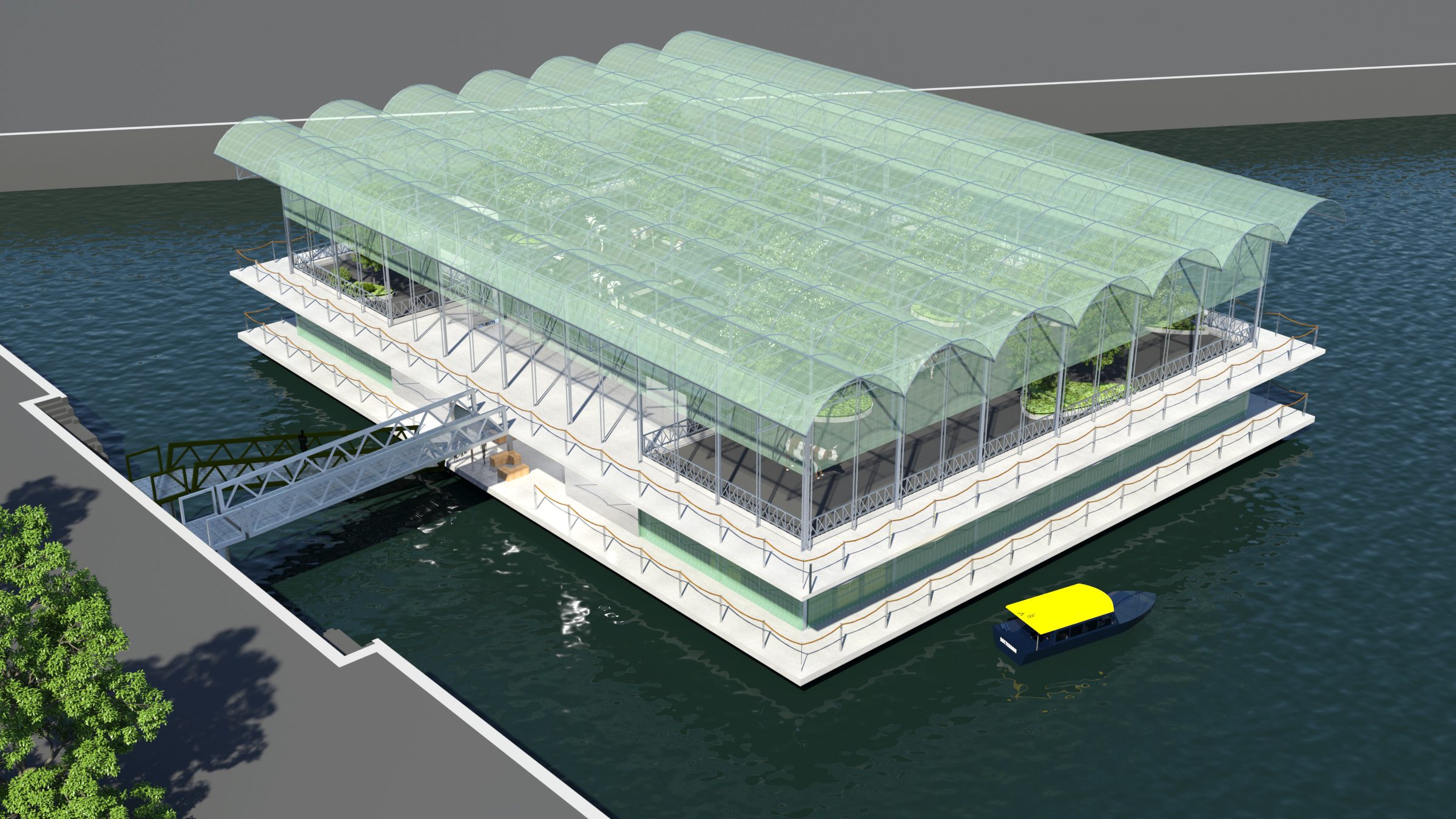

Though the project has been in the works for years, the farm only recently got the green light for construction. Earlier in the summer, a giant, 900-ton concrete platform was lugged by barge from the north of the Netherlands to its current post in Rotterdam’s Merwehaven harbor. It might not look like much yet, but, according to Peter and Minke van Wingerden, co-owners of Beladon, it will soon be a multi-level, hi-tech home to 40 Meuse Rhine Issel cows—and perhaps the best bovine real estate on the river.

According to Peter, animal welfare was a top priority when designing the farm, so the team enlisted the help of a full-time farmer to determine cow-friendly materials, temperatures, feed, and major elements of the design. The finished farm will feature a “cow garden” on the top floor of the building, boasting artificial leafy trees, lush bushes, and sprawling ivy to offer some shade for the cattle. Meanwhile, a soft floor will mimic a natural environment and allow urine to soak through (to mitigate ammonia emissions). To allow the cows more freedom in their milking schedule, a team of robots will be on dairy duty, collecting an estimated 800 liters per day. The milk will then be processed on the floor below and sold locally.

In its leisure time, a cow aboard the floating farm might plod around on the 1,200-square-foot platform, graze on locally sourced fodder, or feast its beady bovine eyes upon the harbor. “This cow will have a beautiful view of the port of Rotterdam,” says Minke. “The farm has three layers … and the cow is standing on top.” However, she points out, a heifer who’s tired of watching the waves can always trot down a ramp to access a small pasture on solid ground.

The building soon to be bobbing up and down in the harbor will certainly have ample curb (or dock) appeal for cows and humans alike, but the real focus of this project is food sustainability. According to Peter and Minke, getting cows on the water might just be a critical step towards creating more resilient, healthy cities.

In a world with a rapidly growing and urbanizing population, Peter points out, there’s an increasing need for more space, more fresh food, and, in turn, more space to grow more fresh food. But when it comes to urban centers, where does that land come from? According to Peter, you have to create it.

“Coming from the Netherlands, it’s an obvious thought to look to the water,” he says. He points out that water spaces across the globe are both plentiful and underutilized—from ports to rivers to large reservoirs. “There’s plenty of space close to the city where we can expand housing or food production. So this is to showcase to the world that it can be done in a very sustainable way in and around our cities.”

The idea first came to Peter and Minke in 2012, while they were working on another project in New York City. When Hurricane Sandy hit, they watched the city’s transportation come to a screeching halt as Manhattan’s roads, subways, and tunnels filled with water. Hunts Point, the Bronx neighborhood housing one of the city’s largest food distribution facilities, had flooded, too. “The trucks could not go in or come out anymore,” says Minke. “After two days, there was no fresh food on the shelves.” For the couple, seeing how quickly an entire city’s access to food could vanish called into question the current systems urban areas rely on to feed their populations.

Amidst the chaotic aftermath, they had a thought: To create a more climate-adaptive method of producing fresh, local food, why not harvest right on the water? “You’re going up and down with the tide, and you don’t need the transport,” Minke points out. Increasingly, floatable buildings are being built to withstand severe hurricanes. Because of their buoyancy, such buildings can simply ride out the tide when water levels rise, bobbing along at the water’s surface. According to Peter, Beladon is involved with several floating building projects in hurricane-sensitive areas, so creating storm-resilient farms is right in their wheelhouse.

But keeping food afloat when storms strike isn’t the only aspect of sustainability the floating farm hopes to tackle. The operation also aims to reduce waste on a citywide scale. “In the past, it was quite normal to dump all your waste far outside the city, so nobody was actually aware about the value of waste,” says Peter. “What you try to do is use and reuse—so your waste is being cycled into new materials, new functions.”

To achieve this, the floating farm’s cow chow will be sourced from local breweries’ spent grain, cut grass from city stadiums and golf courses, and even leftover potato skins that might otherwise be sent to the landfill. The cows will chomp away on tasty waste, in turn providing the city with fresh dairy—and fresh cow pies. According to Peter, the team plans to collect and process cow manure to be used as fertilizer on the farm and throughout Rotterdam. “This is what we call a circular city,” says Peter, “to maintain all nutrients inside the city to use and reuse.”

Though it’s just one small farm, the van Wingerdens see their project as a prototype—a “living lab”—that can be picked up by cities across the globe. “Building on the water is extremely scalable,” says Peter. “And it’s transportable, so you can move it from place to place if necessary.”

Not everyone is fully on board, however. Along with permit issues and potentially pungent farm fragrances, one of the greatest challenges will be getting the public to understand the urgency of the matter. “People do not fear climate change because it’s going in small steps,” says Peter. “We see floods every day on the television screen, and often it’s far away. But we are designing the future in ten, twenty years over here. We feel responsibility for the world after us—for our children, for our grandchildren.”

For this reason, Peter and Minke hope to use the floating farm as an education center, opening it up to Rotterdam residents and curious visitors. In doing so, they aim to raise awareness about the importance of fresh, sustainably grown food and to help people connect with food production in a new, perhaps literal, way. “The cows are very friendly and they like to look in the eyes of the visitors,” Minke offers. “Perhaps they will be cuddled by the visitors!”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook