Why Did This Ancient Marsupial Have Saber Teeth?

Turns out they’re useful if you want to slurp up your food.

The naming of many saber-toothed species—the most famous being the genus Smilodon, or the saber-toothed cat—sounds like a bit of a macabre joke. The pearly grins of these prehistoric predators might have been the last sight of any creatures that got close enough to appreciate them.

But not all saber-toothed things were aggressively predatory. Some, like the marsupial Thylacosmilus atrox, may have occupied a different niche. As a new study published in the journal PeerJ reports, the pouched, cat-resembling creature may have been more of a scavenger, carefully slicing already-dead carcasses a few million years ago with its ferocious-looking dentition. But it wasn’t the eponymous canine teeth that led to this conclusion—it was what the animal was missing.

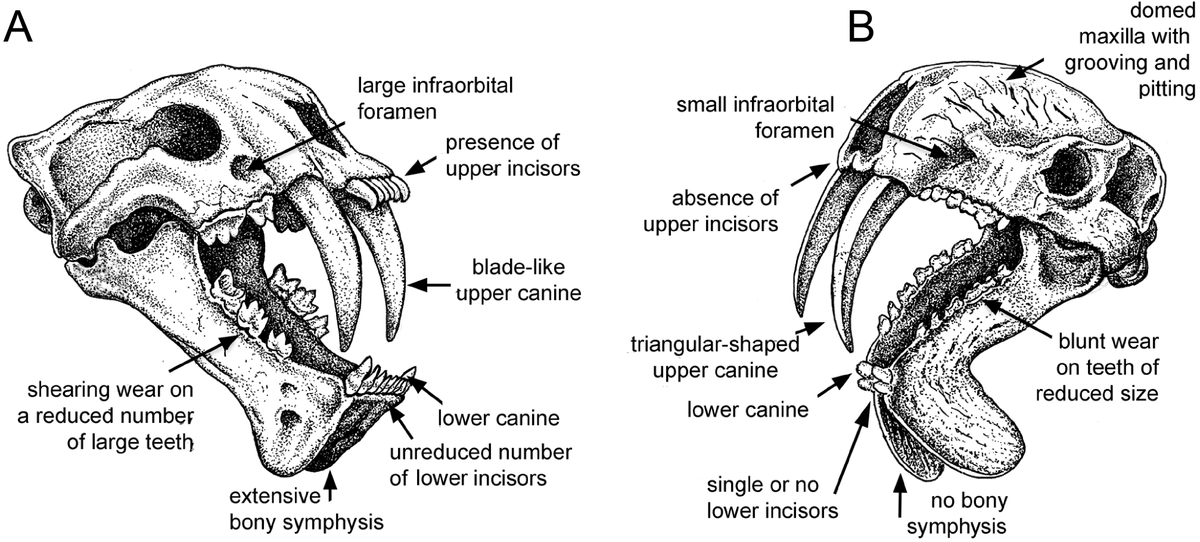

Perhaps the most famous of the saber-tooths is Smilodon fatalis, an apex predator during the Pleistocene, that has very little relation with the marsupial Thylacosmilus (or with modern cats, for that matter), despite their outward similarities. When Thylacosmilus was first excavated in northern Argentina in 1933, the scythe-like fangs led many to believe it had a similar feeding style to other saber-toothed Ice Age predators. But taking another look at Thylacosmilus fossils housed at Chicago’s Field Museum, and comparing them with the skulls and jaws of other mammalian carnivores past and present, told a different story. A team led by Christine Janis, a paleontologist at the University of Bristol, compared Thylacosmilus’s dental hardware and skeletal structure with that of Smilodon. A key difference was visible right up front.

“For me the strangest thing is the lack of incisors,” in Thylacosmilus, Janis writes via email, referring to the front teeth that many predators use for slicing food, “especially when saber-tooths [like Smilodon] have huge, protruding ones that they would need to get meat off the bone when hampered by those big canines.”

Thylacosmilus and Smilodon are an example of convergent evolution—when two or more branches of the tree of life get the same idea, separately. Think of bats and birds, or dolphins and sharks. In this case, though the creatures lived in different epochs, both developed huge canine teeth. Smilodon apparently used them for slicing and stabbing prey, though just how is still a matter of scientific debate. Thylacosmilus, on the other hand, appears to have used them as fine carving knives, like the one you might use to get around the bonier bits of a Thanksgiving turkey.

“We see this in animals that engage in slurping,” says Larisa DeSantis, a paleontologist on the team from Vanderbilt University who specializes in dental microwear, or the study of the microscopic topography of teeth. “The idea is that it was cutting up the carcass and basically slurping the insides out.”

At a time when South America was still an island, Thylacosmilus did not occupy Smilodon’s apex niche. Large “terror birds,” which could grow taller than a person, with a two-foot long skull that was mostly beak, may have been the dominant carnivores. Thylacosmilus appears to have filled a unique ecological niche, one that even modern scavengers, such as the relatively indiscriminate, bone-chomping hyena, don’t quite fit: a scavenger that was careful with its food, targeting the softest tissues, such as internal organs rather than muscle or bone.

“A specialized ‘gut chomper’ diet is not seen in living mammalian predators, and so remains difficult to definitively show for Thylacosmilus, short of a time machine,” says Jack Tseng, a paleontologist at the University of California’s Museum of Paleontology, who is unaffiliated with the recent study, via email. “I think they’ve demonstrated at the very least that the conventional interpretation of Thylacosmilus as a saber-tooth cat–like predator ought to go extinct.”

Comparison of the two kinds of saber-tooths is a great lesson in evolution, and a reminder that it can take many paths. “Thylacosmilus is more similar to possums or kangaroos [than saber-tooth cats],” DeSantis says, “and we are more similar to saber-tooth cats, than these animals were to each other.” Chew on that.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook