The Forgotten Women Aquanauts of the 1970s

These scientists spent weeks underwater doing research—and convincing NASA women could also go into space.

Among the 80,000 images in the photo library of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—along with historical charts, whales and coral reefs, and many, many storm-tossed ships—is a picture that seems to beg for further explanation. Five smiling young women in matching short red wetsuits sit on the edge of an orange pontoon in the bright tropical sun. The enigmatic caption: “In 1970, all female team performed as well as males in scientific sat mission.”

That, according to marine biologist Alina Szmant, who identifies herself as the second woman from the right (“the one with the coquettish grin”), is a bit of an understatement—and only part of a story that was for her “an experience of a lifetime.” In fact, according to Szmant, the first all-female experiment in underwater living (“sat” refers to “saturation diving”) was an undiluted success.

“We performed admirably,” Szmant says, of the 14 days she and her colleagues spent living and working in a submerged laboratory known as Tektite more than fifty years ago. “We spent more hours in the water doing science than any of the male groups.”

Of course, Szmant and her fellow aquanauts never set out to prevail in a submarine battle of the sexes. They were there for the scientific opportunities—and for the adventure. And although the Tektite project may be little remembered today, its impact on research, exploration and the history of women in science has been quietly profound.

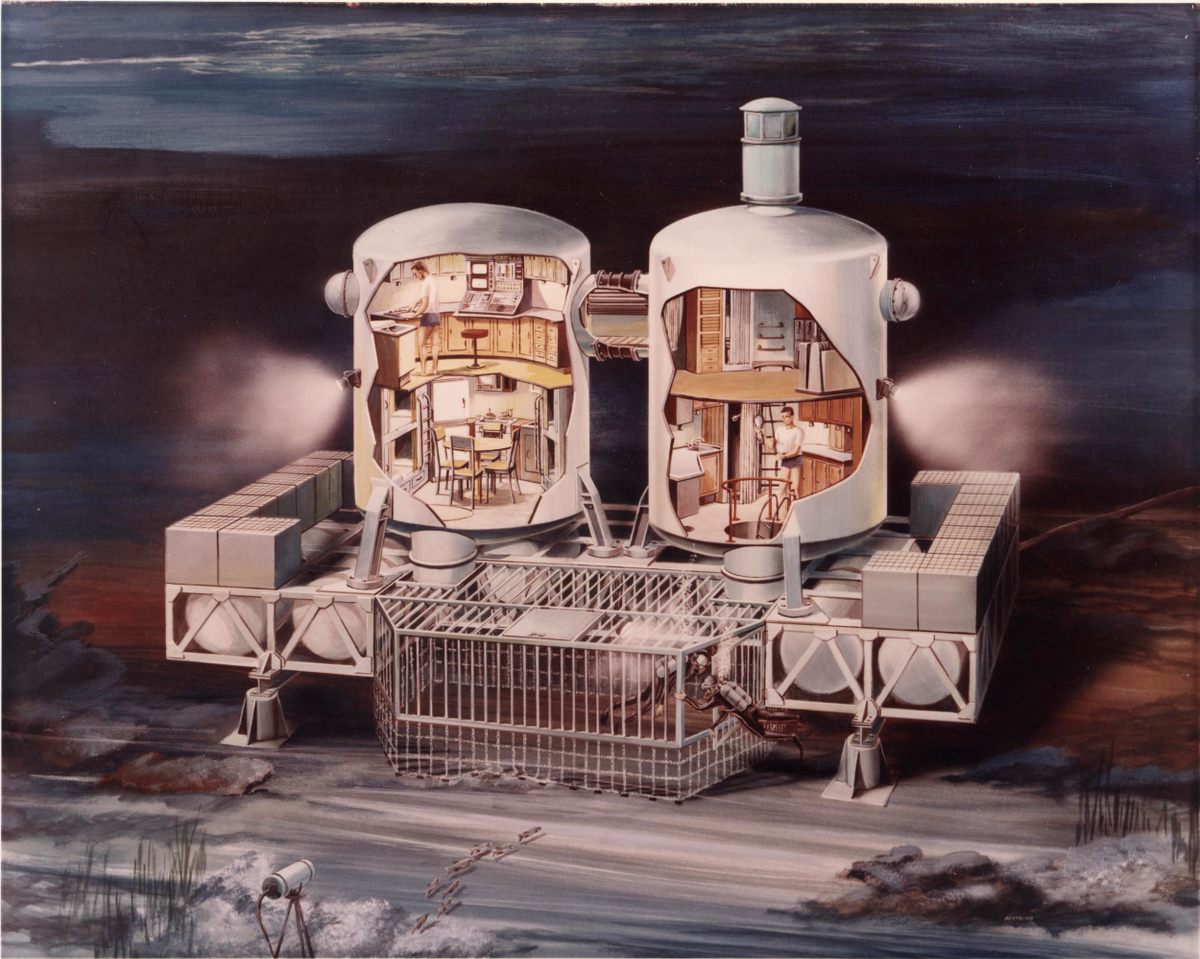

Szmant was a graduate student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography when she heard about an intriguing request for proposals put out by the U.S. Department of the Interior and NASA. They were looking for a team of scientists to spend two weeks in the Tektite underwater habitat, parked off the shore of St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Named for a type of glassy pebble sometimes formed by meteorite impacts, Tektite consisted of two 18-foot-high metal cylinders connected at the base. Inside was a lab and storage space, a small kitchen with a Harvest Gold refrigerator and microwave, a tiny bathroom and no-frills bunks. Its original inhabitants, the year before, had been a team of male scientists whose primary research goal was to see whether they experienced any adverse effects from spending two months underwater.

“Man had walked on the moon, but NASA was thinking about longer missions,” Szmant explains. “They were interested in the medical and psychological side of things—what happens when people are isolated from society and have to live with only a few other people?”

NASA hoped that the undersea environment could stand in for space, and in a way it did. To live at that depth, the aquanauts had to remain under pressure the entire time, their bodies saturated with nitrogen to counteract the effect. With at least 19 hours of depressurization required to avoid the bends, hasty escape to the surface was impossible.

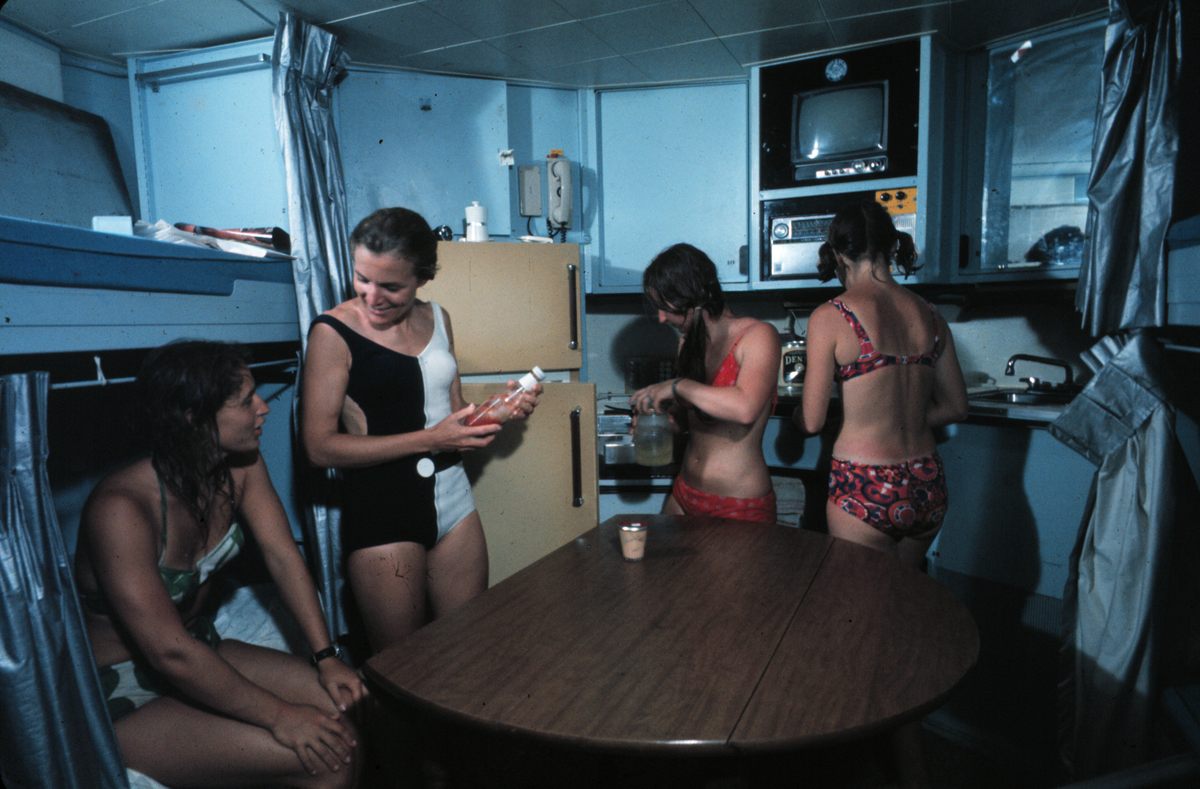

Still, the men were not as isolated as they might have been on a Martian mission. They watched TV, put away stacks of frozen dinners and stayed in constant communication with the surface. No serious problems arose. The next step, the project’s leaders decided, would be to find out how scientists might conduct real research under these conditions. And that’s where Szmant came in.

Along with her friend Ann Hartline and Ann’s husband Peter, Szmant proposed to study the behavior of small coral reef fish. Their application was accepted, along with a proposal by Renate True, an oceanographer at Tulane University who had been on dives with Jacques Cousteau, and another by Sylvia Earle, a Harvard University research fellow who, two decades later, would become NOAA’s first female chief scientist.

The proposals for what became known as Tektite II came from men and women scientists, but government agencies were leery of coed missions—and the public relations potential of an all-female team at a time when the feminist movement was gaining strength had clear allure. All that was needed was a woman engineer to maintain the habitat’s life‐support systems. Peggy Lucas Bond, a graduate student in electrical engineering at the University of Delaware in an era with few women engineers, had once been a lifeguard, so after completing a scuba program run by former Navy Seals, Bond, too, was bound for Tektite.

Their scientific credentials may have been solid, but as they prepared for their mission it didn’t escape the media that the five women aquanauts—Szmant, Bond, Hartline, True, and Earle—were also good-looking young brunettes.

“The average height of team members is 5 feet 3 inches and the average weight 110 pounds,” reported the Associated Press, in all seriousness. “They all wear their hair longer than shoulder length, pulled into pony tails or braids.” Lest readers worry about the effects of salt water on that long hair, the article also noted: “They will have one concession to femininity—a hair dryer in their living capsule 50 feet below the surface. But they do not plan to spend much time primping.”

The women who moved into Tektite in July 1970 also had little time to dwell on sexist media coverage—there was more than enough work to occupy them. Sophisticated rebreathers—a newly available technology—let them venture into the coral reefs and seagrass meadows surrounding the station for up to eight hours at a time. It was exhilarating, but also exhausting.

When not diving, the women spent hours sitting in Tektite’s bubble windows watching marine life pass by, as if in a sort of inverse aquarium. At night, many fish were attracted by the habitat’s lights, and Szmant remembers silvery, six-foot-long tarpons staring in at them “with these gigantic eyes: They’re like, ‘What’s going on in there?’”

The Tektite crew’s research findings would lead to published papers, but—at least from NASA’s perspective—it was the aquanauts themselves who were the real experiment, and their return to the surface at mission’s end represented a triumph, celebrated with a ticker tape parade in Chicago and a formal luncheon at the White House with First Lady Pat Nixon. (It was a “circus,” Szmant says, that made them feel “pretty silly.”)

As the attention faded, the five returned to their various professional pursuits. Szmant finished her Ph.D. and became a professor of marine biology. Bond’s career as a computer scientist took her to Hawaii and Paris. Hartline later became an environmental lawyer, and True taught anatomy and physiology in Texas. Earle was the only aquanaut whose fame grew after Tektite; a marine biologist and science communicator, she still holds the world record for deepest dive by a woman (1,250 feet, set in 1979), a feat that won her the nickname “Her Deepness.” True died in 2017, but the other four would reunite in 2020 for an online conference marking 50 years since their mission.

Tektite itself hosted a handful of other, all-male missions before it was shut down and put into storage at a Philadelphia shipyard. In 1980, a nonprofit restored the habitat with the aim of putting it into service again, but without the funds to submerge it Tektite again deteriorated. Its metal was eventually recycled.

Despite its ignominious end, Tektite’s legacy continued with new generations of undersea habitats—including the Aquarius Reef Base in Florida, which NASA astronauts have used as a stand-in for space, the moon and even Mars. Lessons learned from Tektite—including about remote communications, group cohesiveness and even menu planning—informed NASA’s first space station, Skylab, launched in 1973. Meanwhile, Tektite II’s all-female mission furthered the idea that women could perform as well as (or better than) men in extreme environments, providing evidence that helped encourage NASA to begin training women as astronauts in 1978.

“Tektite made it easy for them to say, ‘Okay, we can put women up there as well,’ which they have done—and which was quite a success,” says Bond, who over the past half century has watched humanity explore space with a sense of personal pride, knowing that she played a small role in making it all possible. “I think it’s very, very important. I contributed, and I’m pleased that I did. “

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook