The Return of Swiss Cheese Baths

Melting into a tub of whey has a long history in the Alps.

The rustic-looking copper tub is filled to the brim with a greenish-yellow liquid, thankfully hidden beneath a milky froth. It’s not brackish water; my outdoor tub is full of whey. I dip my foot gingerly only to yank it out again. It’s scalding.

This whey bath is a steamy byproduct of making cheese. It doesn’t take much to make cheese—just a few hundred litres of milk and a sprinkle of precision. When milk, rennet, and cultures are heated to around 45-60 degrees Celsius (113-140 degrees Fahrenheit), they transform into two products: curds and whey. Curds become cheese. But dairy owners have never quite known what to do with whey. It has run the gamut from sought-after medicine to problematic waste product to pig feed to … niche bathing liquid.

I’m at a small family-owned dairy in the Swiss Alps, where curds have likely just been removed from this whey bath. The young Czech farmhand assures me that he has whey baths all the time on his family goat farm back home, and that his skin is softer for it. Comforted, I slide into the foam.

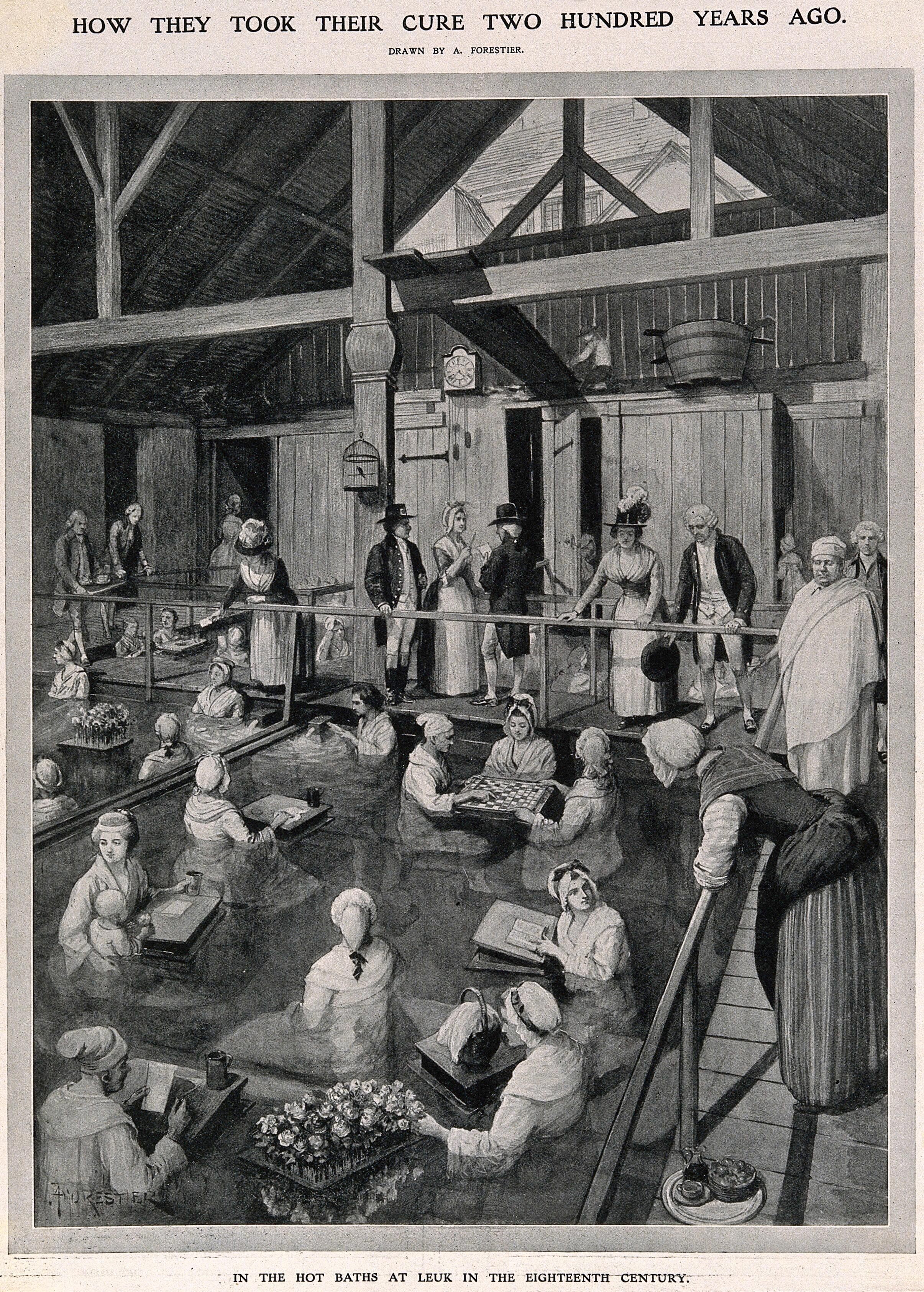

Had I been afforded this opportunity a century or two ago, I would likely have been either physically unwell, wealthy, or both. From the 1500s to the early 1900s, spa tourism, including thermal and whey spas, were all the rage in Switzerland. The Molkenkur (whey cure) or Gaisschottenkur (goat’s whey cure) inspired the bourgeoisie of Europe to seek out the restorative effects of whey in remote villages in the Swiss Alps, many of which constructed fashionable health resorts.

The popularity of whey extended as far away as London, where whey was used not only as a liquid medicine, but also as a popular drink, similar to coffee today. Nevertheless, for medicinal qualities patients preferred Swiss whey. As one British doctor noted in 1869, “There is a general feeling in favour of Swiss whey; and if they are not in Switzerland, patients are gratified to learn that the whey is made by a native of Appenzell, and still better pleased, if the said native shows himself in his national costume.”

That said, a proper Molkenkur was intended to be a holistic experience. Johann Heinrich Heim, a Swiss spa doctor in the 1820s in Gais (a village in Appenzell where the Molkenkur is said to have originated), outlined a therapeutic whey-cure regime. He advised patients to drink 9-12 glasses of whey per day, interspersed with short walks or hikes to the surrounding mountains, plentiful relaxation, and regional food. This would last anywhere from two to eight weeks, depending on the severity of the illness. Whey bathing became a natural extension of these curative experiences and were widely available in whey spas across the country.

At the time, whey baths fit into a larger accepted category of “bathing cures,” which were administered at spas that served as important medical and recreational hubs. Many physicians believed that genetics or lifestyle factors caused disease, particularly climate and location, so advised spa visits in alpine landscapes as “change of air” cures. By the 1870s, guides listed more than 150 medicinal springs in Switzerland, which often specialised in diseases such as nervous disorders, gynecological issues, or skin rashes. Doctors prescribed both bathing regimes and drinking therapies of mineral water. In the context of medically administered leeches and laxative purges, it’s not surprising that spas and whey baths were welcome diagnoses.

Nowadays, mentioning whey baths or whey spas to Swiss people often draws bemused expressions. In a few short generations whey went from a luxury medicinal liquid to a waste product. The disruption of the two World Wars and the advent of modern pharmaceuticals have been blamed, but perhaps the industrialisation of the dairy industry is the biggest culprit.

One kilogram of cheese produces nine litres of whey. As cheese production soared in the 1900s, disposing of whey became a pressing problem across the globe. Cheese producers have used whey as animal feed or sprayed it as a fertilizer over fields. But these solutions provide low returns, and whey is odorous and often too saline for the soil. Dairies have also tried (and perhaps still are) pouring whey into waterways, to the detriment of the environment. Whey’s high organic-matter content means it has a high Biological Oxygen Demand and Chemical Oxygen Demand. By removing oxygen from surrounding waters, it can effectively suffocate aquatic life in high quantities.

Most countries now strictly regulate the disposal of whey. Of the 13 million tons Switzerland produces during cheese production each year, around 75 percent goes to animal feed, with the rest used for food products and, more recently, biogas production for fuel. But Doris Erne, managing director and owner of Wheycation, a Swiss company that creates shakes and protein powders from Swiss whey, believes the country can do better.

“Whey is the perfect food, it’s perfectly safe. It’s good,” says Erne. “A lot of producers would be happy to just give us the whey [to get rid of it]. But there isn’t a market need for a whey drink, or whey as it is, so you have to put effort into it, to build a market. It’s quite a lot of work and not a lot of producers are willing to do that.”

Admittedly, whey is a bit of an acquired taste. It’s like a sour, watery yogurt. And it’s yellowy green.

But greater environmental protections, technological and scientific advancements, societal pressure for a circular economy, as well as health trends towards functional foods have quite literally turned whey from “gutter-to-gold” as Geoffrey W. Smithers puts it. A research scientist, entrepreneur, and food-industry consultant, Geoffrey has been observing the evolution of whey for more than a decade now.

“With the application of modern scientific techniques, we are starting to understand why these people [in the past] were drinking whey and even bathing in it. They didn’t really understand why whey was working, they just knew it worked from an anecdotal perspective,” he says. “But now we understand why. We’ve got a lot more information, even in the last 20 years, about why various components in whey are beneficial to human health.”

Smithers says that the only reason he would bathe in whey, however, would be for its wound-healing properties. Smithers worked for a time on a medical trial that tested whey-based products on wounds. Although the healing wasn’t deemed significant enough for the research to proceed, Smithers says there was still some benefit.

As a drink, whey contains nutritious proteins, such as β-lactoglobulin, α-lactalbumin, and lactoferrin, which are a rich source of amino acids (needed to make proteins and essential for a variety of bodily functions, including muscle building and immune function). The benefits of various whey proteins have also been implicated in studies for their weight-management properties, wound care and repair, infant nutrition, anti-cancer effects, and even for the treatment of Covid.

It appears that there might have been something special about the Molkenkur after all. Health-focused whey drinks are rising in popularity, and although whey bathing remains a niche activity in Switzerland, it too is experiencing a renaissance, albeit as a novelty more than a healing practice. I suspect clientele are riding the post-pandemic wellness wave right into the relative isolation of the Swiss mountains. I know I did.

Gathering my courage, I immersed myself in the whey bath, which smelt encouragingly of warm, fresh milk. I let myself relax to the sound of cowbells, drinking in the sight of the Alps, exactly as they must’ve done 150 years ago.

If this is therapy, then I’m all for it.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook