Reclaiming Georgia’s Stone Mountain Through Haunting Landscape Images

Photographer Sheila Pree Bright wanted to find a new way of seeing the site and its connection to centuries of racism.

It was a windy day when photographer Sheila Pree Bright brought her father’s Bible to the site of her latest project. Just east of Atlanta, and towering beside the city named for it, the lone, massive chunk of granite that is Georgia’s Stone Mountain looms large in the history of the American South, the Confederacy, and the legacy of racism. Bright went to the mountain to photograph it, and to tell its story in a new way. “I get emotional about it,” she says, remembering the moment, years later, when she feels her late father endorsed her effort.

According to Georgia law, Stone Mountain in its entirety is a designated memorial to the Confederacy. The north face of the mountain is home to the largest bas-relief sculpture in the world, depicting Confederate leaders Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, and Stonewall Jackson on horseback. The idea for the carving came from Helen Plane, a member of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, in 1914. After watching the infamous film The Birth of a Nation, Plane also expressed admiration for the Ku Klux Klan, going to great lengths to include them in the memorial. At the time, the mountain was owned by the Venable Brothers, who granted the Klan access to the mountain for their rituals. On November 25, 1915, Alabama preacher William J. Simmons held a ceremony at Stone Mountain announcing the second coming of the Ku Klux Klan.

The mountain’s history was raw for Bright when she began work on two series, “Behold the Land” and “Invisible Empire.” The photographs are meditations on the Georgia landscape, specifically Stone Mountain and its haunting history. Selections from both series are featured in an exhibition called The Rebirth of Us at Atlanta’s Jackson Fine Art Gallery.

It’s Bright’s latest chapter in a career that began with the desire to capture the lives and experiences of communities that have been historically overlooked. Now, from taking portraits of ’90s rappers in Houston, one of the birthplaces of Southern rap, to documenting the 2014 and 2015 Black Lives Matter protests, Bright uses photography to challenge dominant narratives and to put contemporary stories into social and historical context.

Atlas Obscura spoke to Bright about the exhibit, the choice of doing landscapes, finding inspiration in the essays of W.E.B. Du Bois, and what she hopes viewers will take away from her work.

You’ve mentioned you grew up in Germany, at the military base where your father was stationed, and weren’t really exposed to Black culture. What draws you to the subjects that you photograph now?

The people, especially African-American people. When I was photographing the portraits of the men who wanted to be rappers, they came out with guns and all for me to photograph and they said, “you’re like a white girl in a black body.” So for me, photographing African-American people was the experience of searching for home.

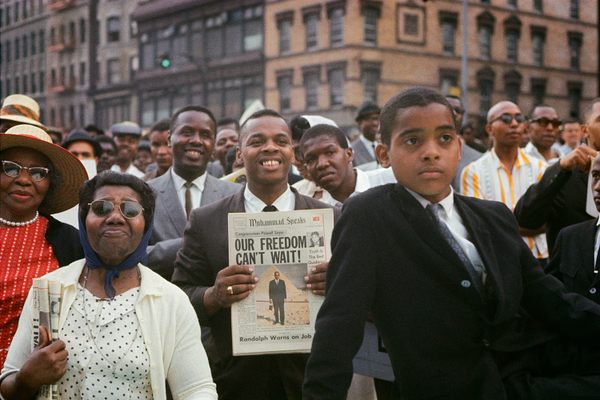

I look at what is going on in pop culture, too, and how it affects marginalized communities. For example, when you look at the #1960Now series [Bright’s 2018 portraits that connect the Civil Rights and Black Lives Matter Movements], I was very curious about the young people back during the Civil Rights Movement and I started thinking about it generationally. With all the stuff that was going on with Black bodies, I had to go to the ground and photograph. That’s what started that series.

How did your Stone Mountain project come about?

For seven years, I was photographing the project #1960Now, lecturing, and exhibiting all at the same time. I didn’t realize until after 2017 that I was actually traumatized and needed self-care from being on the ground, what I’ve seen, what I’ve experienced.

The photo editor of the Washington Post called and wanted to commission photographers to do a photo essay about racism. I said, “oh my God.” I was so exhausted but I knew I needed to talk about it in a different way. I live 10 minutes away from Stone Mountain and as an artist, I wanted to show different ways of seeing, to unpack instead of just photographing people.

We learn of each other through the media and it’s always negative, especially when it comes to us [Black people]. So I wanted to challenge myself to do landscape. I started reading a lot about the land by reading essays by W.E.B. Du Bois; one of them was called “Invisible Empire.” It’s about how Georgia is so beautiful but yet … there’s something strange and disturbing.

The Washington Post photo editor told me that I had to shoot people but I said no, I don’t. I wanted to make these landscape photographs beautiful because it [Stone Mountain] is beautiful but it has all this symbolism with it.

I think the idea of doing landscapes came before the essays, but what the essays informed me about is how to do them. In “Behold the Land,” Du Bois was talking to a group of Black and white young people about how to move forward. If you think about it, it’s all about the land. That’s what really inspired me even more to really challenge myself with the land.

Why did you choose to do black-and-white photos for the “Invisible Empire” and “Behold the Land” series?

I made them in black and white because if you think about the Confederacy and The Lost Cause, nothing has really changed. We have progressed, yes, but yet, we’re still in the same place. Why can’t we change?

We always talk about change. We talk about diversity. And when the George Floyd protests happened, everybody from PR was doing all this, “I’m with Black Lives Matter,” things but to me, that was just a front, to be honest.

The images in black and white are very haunting, beautiful, and magical. This was actually liberating for me to be on that mountain and to deal with all of that symbolism. How do we, as a society, move forward with all of this? Because if we do not unpack any of this, it’s constantly going to continue. As long as the silence is there, we’re not going to be able to move forward. This work, for me, is presenting a liberation and figuring out a way for us to move forward.

When you went to Stone Mountain to photograph the landscape, what was going through your mind?

My parents are from the Jim Crow era. They are both passed now. As a child, my parents did not talk to us about the Civil Rights Movement and when I started coming to the South, when I started working on #1960Now, I said to my mom, “why didn’t you ever talk to us about the Civil Rights Movement?” She said that she didn’t want us to hate white folks. When my parents passed, there was a lot of stuff that was going through my mind because we’re all born into a movement, whether we’re conscious of it or not.

I can’t talk to them right now but when I got to that mountain, I was feeling the ancestors, I was feeling my parents and asking them questions about their experiences and being so young and how they dealt with that trauma.

I did a lot of research on the Lost Cause and the Confederacy. I didn’t realize that white women were responsible for funding all of these monuments. They also had rituals and ceremonies in schools about the Lost Cause. Young people at the ages of four and five years old were writing essays about the institution of American slavery. One of the books that I was reading talked about how one boy won an award for talking about how the slaves were better off being slaves. This pulled me away.

The second coming of the Ku Klux Klan was created on that mountain and they read Romans 12. So I brought my father’s Bible up there and I laid it down. It was a windy day. It was in Romans but not in that chapter and I swear to you, when I started to photograph the page it was on, the page changed to Romans 12. I get emotional about it because I felt that my father was speaking to me with that.

How can we reconcile how we feel seeing Stone Mountain’s beauty while also being aware of its dark history? How are your photographs part of that reconciliation?

Even though we are still dealing with the trauma, we have to think about how we move in the future and how we heal, because I don’t believe racism is going anywhere. Another part of the reason I chose landscape is because the land is so important. Across the world, if you think about it, a lot of the people that are hurting because of the land are people of color.

I think it’s about reclaiming the mountain. Indigenous people were living on that land first. There was also a town in Stone Mountain where Black people lived that nobody talks about [Shermantown, a late 19th-century African-American shantytown named after the Union General William T. Sherman]. For me, it’s about reclaiming through the violence and darkness that was there because if we don’t do that, we’re going to be constantly internalizing that.

What do you want viewers to take away from your work?

When I think about Atlanta, I think about how violent the Antebellum South was. I spoke to an elder named Lonnie King who started the Atlanta Student Movement [in 1960]. One thing that he really instilled in me was that you’re never going to get the masses of the people. He said that even though you would think there were a lot of people on the ground, there really weren’t. But those who were, who fought for human rights and civil rights, helped the culture move forward. So for me, if I can inspire one person to go talk to their children or grandchildren to talk about our history, the violence that many faced, I would have done my job.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook