How Did the Chess Pieces Get Their Names?

One player’s pawn is another’s farmer. And at one time, the queen was the virgin, and rather powerless.

A game of chess is like a Chinese newspaper: a set of symbols that can be understood by people who speak different languages. In the Chinese example, Mandarin and Cantonese speakers can read and understand the same text, even though they use different words for the same concepts.

Chess, too, is perfectly intelligible by participants who share no other communication skills. But scratch the surface and the standardized game reveals a multitude of linguistic particularities. One player’s pawn is another’s farmer. What you may call a bishop, somebody else knows as an elephant. Or a fool.

Chaturanga to Skák

Chess took a millennium to conquer the known world. It first emerged in India in the early 7th century as chaturanga, finally reaching Iceland as skák around 1600 A.D. See Big Think’s Strange Maps piece for an itinerary of the game and an overview of its various names across the world.

As it moved west toward Europe—first passing through the Persian and Arab cultural filters—the game maintained its board, pieces, and most of its rules. Yet it also underwent some subtle and not-so-subtle tweaks. In a sense, the symbolic representation of an Indian battlefield turned into a sublimated form of medieval tournament.

Not only the game itself, but some pieces also assumed different identities as they entered new cultural spaces. Others, however, stubbornly clung to their origin stories. Some of those differences have interesting histories. But intriguingly, other differences remain shrouded in mystery.

Pawnography

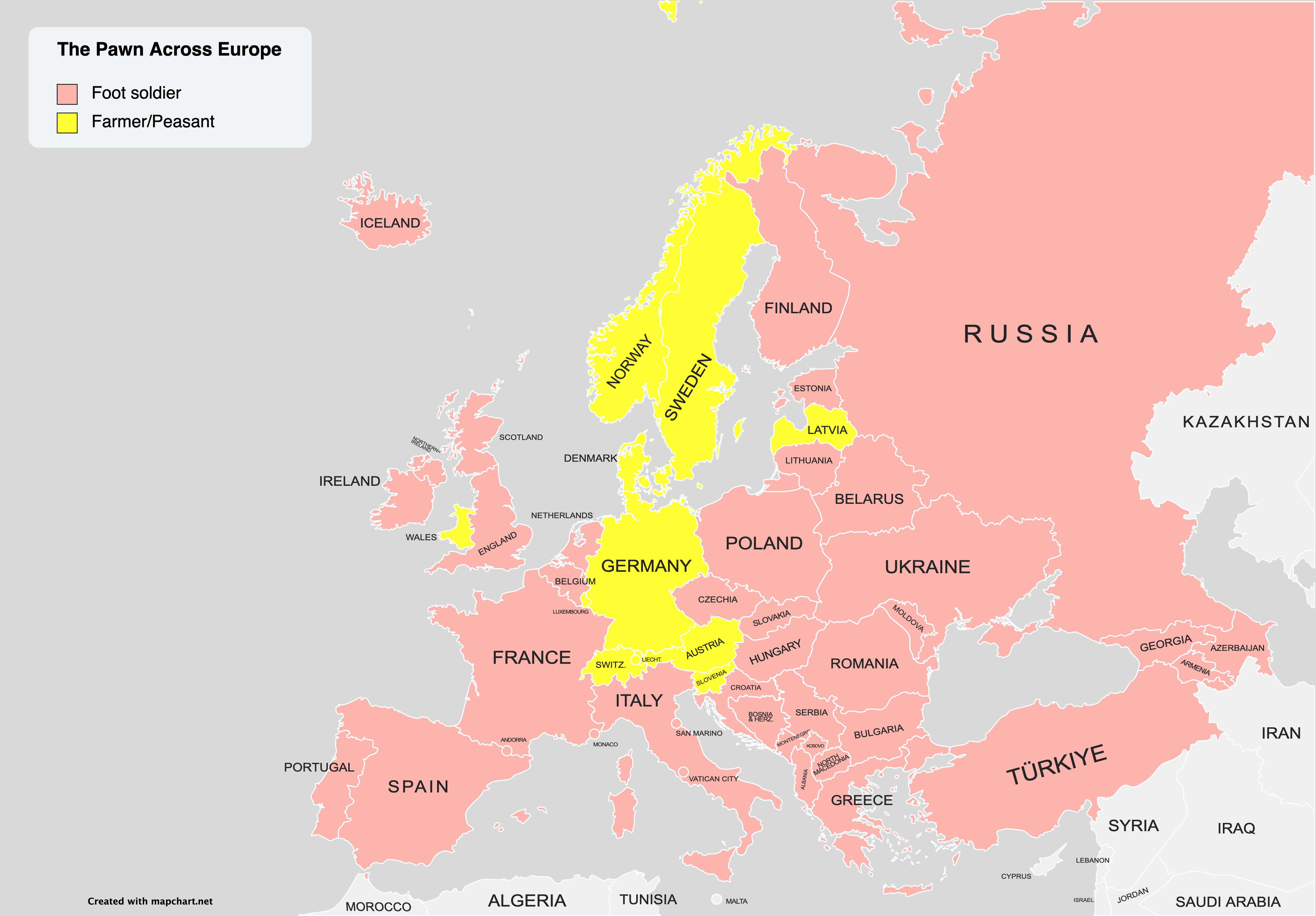

The notion of the pawn as a “foot soldier” is fairly consistent throughout the history of chess, with the Indo-European root for “foot” echoing all the way from the original Sanskrit padati, via the Latin pedester to modern French pion (and imported into modern Turkish as piyon) and English pawn.

Other terms are available: In old French, pawns were called garçons (“boys”). Additionally, pion is sometimes said to derive from espion (“spy”).

Interestingly, the Spanish term peon also means “farmer,” which is the term used across a number of Germanic languages and a few others (e.g. bonde in Danish, kmet in Slovenian)—no doubt because in times of war, farmers were the most obvious source of cannon fodder.

Have Horse, Will Jump

From the very beginning of chaturanga, this piece—originally called asva, Sanskrit for “horse”—has firmly maintained its equine association. Of course, this is likely because it is the only piece that is able to jump over the heads of the other pieces. As the map shows, the variation in nomenclature is fairly limited: The piece is either named after the animal (e.g., caballo in Spanish), its rider (e.g., riddari in Icelandic), or the movement it makes (e.g., springare in Swedish).

Because of this proximity in meaning, and the fact that the piece is usually styled like a horse, adjacent concepts are often used interchangeably. In Hungarian, for instance, the official term is huszár (“knight”), but the piece is also colloquially called ló (“horse”). Similarly, in Czech the piece is a jezdec (“rider”) but often simply a kun (“horse”).

For Those About to Rook

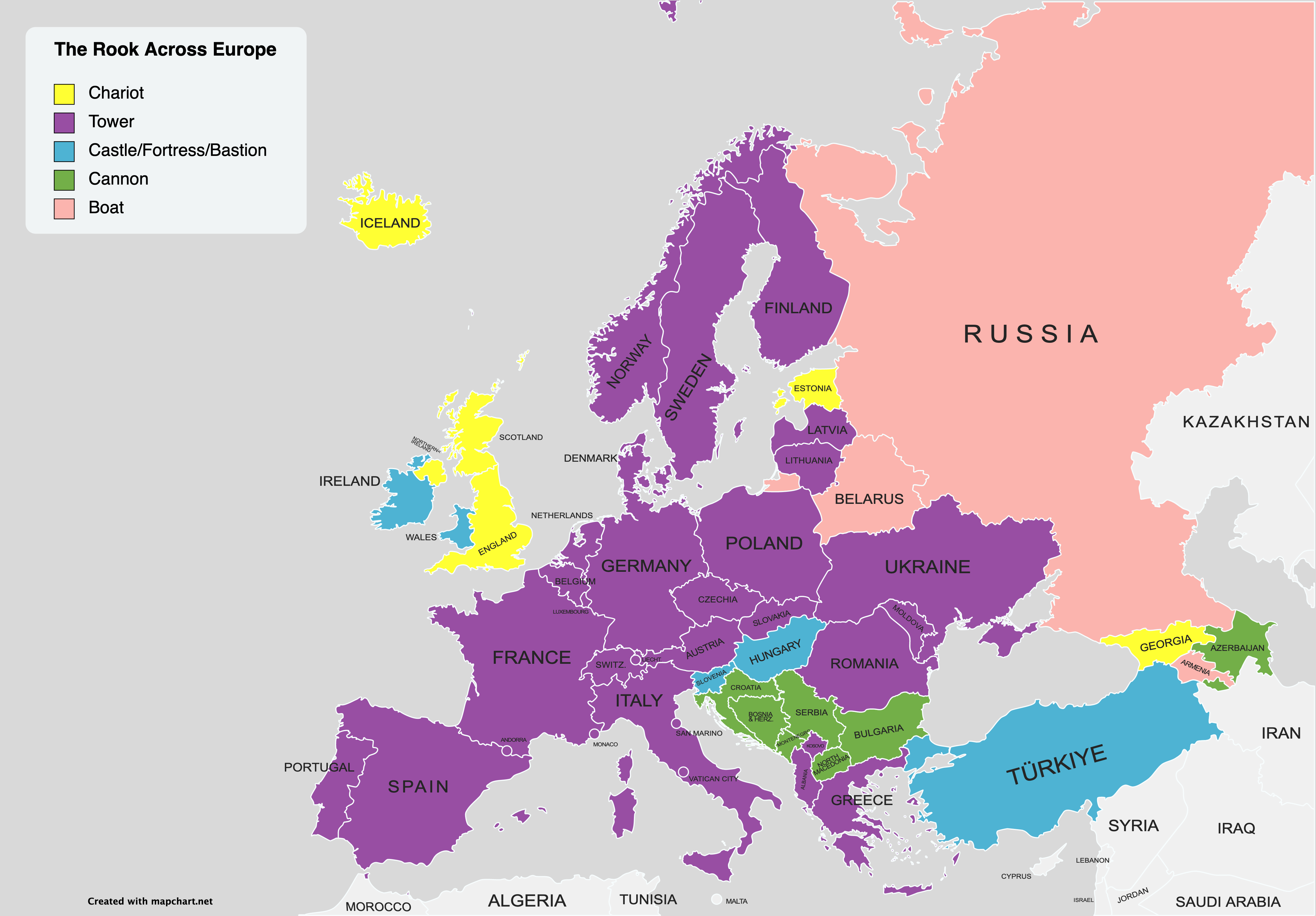

In the earliest versions of the game, this was a “chariot”—ratha in Sanskrit, rukh in Persian. Yet in many languages across Europe, this piece is known as a tower or a castle. How did that happen?

One theory is that the Arabs transmitted the Persian term rukh almost unchanged to Europe, where it turned into old Italian roc or rocco. That’s virtually identical to rocca, the old Italian term for “fortress,” which association in turn gave rise to alternate names for the piece: torre (“tower”) and castello (“castle”).

Another theory is that Persian war chariots were so heavily armored that they resembled small, mobile fortifications—hence the link between rukh and castles.

A third idea is that the people-carriers on the backs of elephants in India, called a howdah and used in war to attack opponents, was often represented as a fortified castle tower in chess pieces from 16th- and 17th-century Europe. The elephant eventually disappeared, while the (Persian) name stuck.

With a good old-fashioned siege in mind, it is not such a big leap from castles and towers to “cannon,” which is what the piece is called throughout the Balkans.

What is more puzzling is that the rook is called “ship” (or “boat”) in some other languages, including Russian (lad’já) and Armenian (navak). Could there have been a translation mishap? Rukh is Persian for “chariot,” while roka is Sanskrit for “boat” (but no early chess piece was ever called roka). Or is this because Arab rooks often were V-shaped, like a ship’s bow? Or because the piece moves in a straight line, like a ship?

Nobody knows for sure. However, ancient Indian chess sets visualized this piece as an elephant. And indeed, in Hindi and several other Asian languages, the piece is still called “elephant.”

Elephant Goes Episcopal

No chess piece elicits a wider range of epithets across Europe than the bishop. It starts as another elephant, except that this piece was actually called “elephant” in Sanskrit (hasti) and in Persian (pil). That was Arabized as al-fil, which was Latinized as alphilus.

In French, that became fil, fol, and finally fou, which means “fool” or “jester.” That term was the result of a chain of whispers, which was then faithfully translated into Romanian. Another whisper changed alphilus, which means nothing in Italian, into alfiere, which means “standard bearer” in Italian.

The wide range of this piece’s movements explains terms such as “runner” (e.g., Läufer in German), “hunter” (e.g., lovac in Serbian), “gunner” (e.g., strelec in Slovak), and “spear” (oda in Estonian). The Russians are among those who have maintained the original “elephant,” called slon in Russian. But in the past, it has also been called a durak (“fool,” probably a loan from the French) and an offizer.

Officer and/or nobleman is a rather generic term. A notable alternative to the official Bulgarian term ofitser (“officer”) is fritz, derived from the nickname for German troops during World War II—a relatively recent innovation, probably helped by the fact that it sounds similar to the official term.

Apart from English, only a few other languages call this piece the “bishop”: Icelandic, Faroese, Irish, and Portuguese. Why? Nobody really knows. The miter-shaped appearance came after the name. The term does have some pedigree: The Lewis chessmen, carved from walrus ivory in the 12th century, already have the bishops dressed in recognizably ecclesiastical garb.

The Virgin and Other Versions

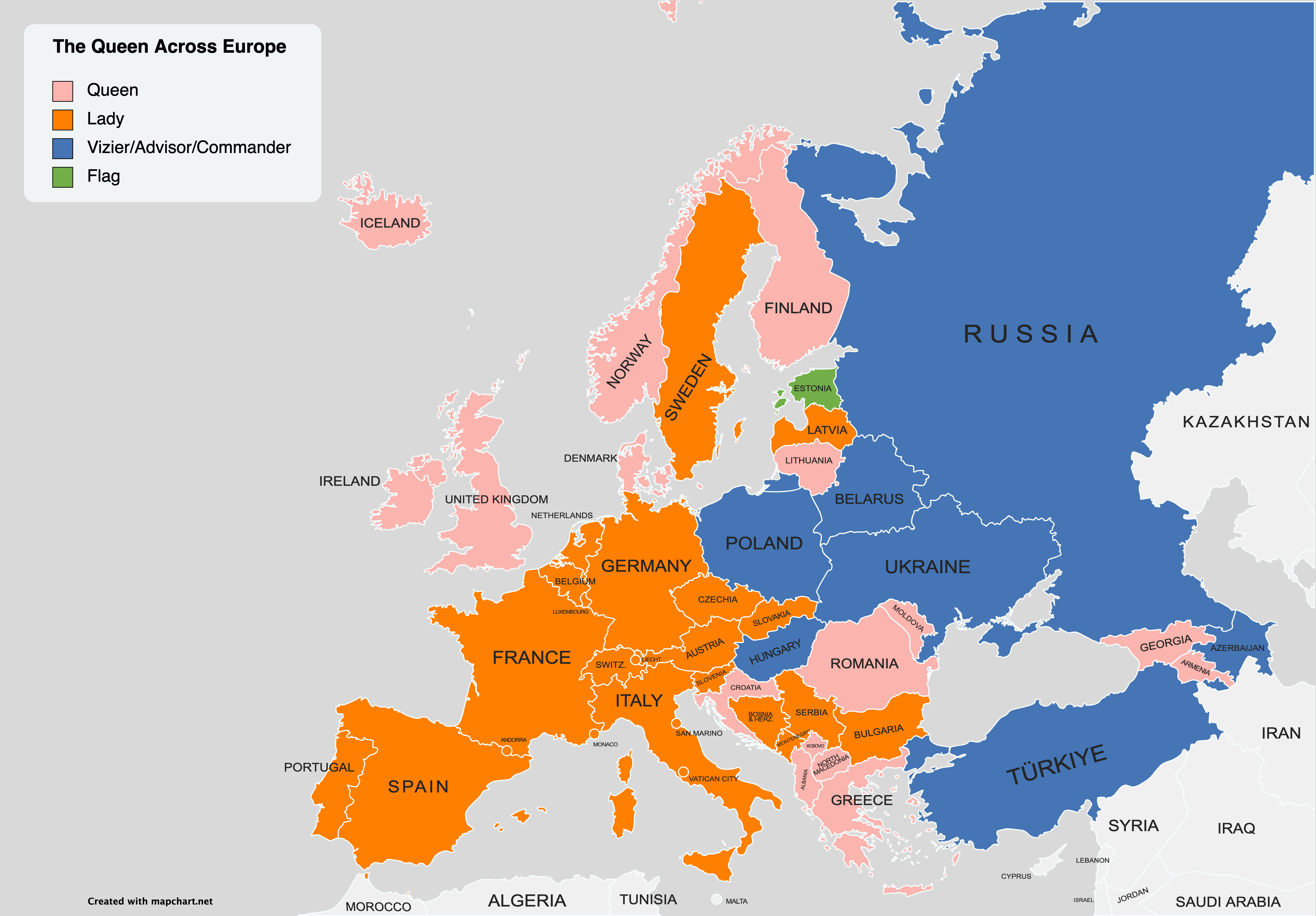

While it may seem logical that the king has a queen by his side, that’s not how things started out. In the Indian original, this piece was the king’s “counselor” (mantri in Sanskrit). The Arabs used wazir (“vizier,” i.e., the ruler’s minister/secretary), which was Latinized to farzia, which became the French vierge (“virgin”).

That was an intriguing mistranslation because, in large parts of Europe, the trend was to feminize the king’s companion. A manuscript from around the year 1000 contains the first mention of the piece with the name regina (“queen”), possibly a Byzantine innovation. In the 14th century, reine (“queen”) replaced vierge on the French chessboard, and a century later, reine herself was replaced by dame (“lady”). This may have been a borrowing from the game of checkers.

Why did the king’s counsel become his consort? Three (possibly complementary) theories circulate: the religious cult of the Virgin Mary, the literary trope of courtly love, and the relative importance of queens in medieval politics. What is clear, however, is that the piece not only acquired a new, female identity but also greater powers. The mantri could only move one square diagonally, whereas the modern queen combines the straight-line moves of the rook with the diagonal ones of the bishop.

While the piece is called “lady” or “queen” in most European languages, Russian and other Slavic languages retain versions of ferz, the Persian term for “counselor.” Polish uses hetman, a high military rank from Eastern European history. Russian (and other Slavic languages) also variously use(d) koroleva (“queen”), korolevna (“princess”), tsaritsa( “emperor’s wife”), kral (“queen”), dama (“lady”), and baba(“old woman”).

Mysteriously, Estonian calls the piece lipp (“flag”).

One Piece to Rule Them All

Uniquely, the game’s central piece has maintained its original title throughout Europe. In the Indian game, it was called rajah, Sanskrit for “king.” The Persian equivalent shah gave rise to the name of the game itself in many other languages (e.g., échecs in French or skák in Icelandic).

As is well known, “checkmate” derives from the Persian for “The king is dead”—although, when playing against an actual king, a more prudent phrase was used: “The king has retired.”

This piece’s kingly status is a constant throughout the map, from koról’ in Russian and König in German to erregea in Basque and teyrn in Welsh (although the latter word, related to “tyrant,” is a less common Welsh term for “king” than brenin). In Yiddish, the king can be called kinig or meylekh, two words that mean the same, but derive from German and Hebrew, respectively. In Russian, alternate names include tsar (“emperor”) and kniaz (“prince”).

However, in Asian versions of the game, this central piece has a slightly different status: a “general” in Chinese and Korean and a “prince” in Mongolian.

The king can only go one square in any direction, but in the 13th century, he was permitted one leap per game. This eventually evolved into the combination move called “castling,” which involves a rook. The king moves about his castle, so to speak.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook