Making Pottery From the Ashes of the Sonoma Wildfires

A ceramicist is offering people who lost their homes a way to remember—and look to the future.

That night in October 2017, Aimee Gray didn’t realize anything was wrong until she heard Brighton barking. Her 160-pound mastiff was making such a commotion, and Gray looked out the window to see flames licking toward her ranch house in Santa Rosa, California. She ran to shake her husband awake, and said, “I think we’re in a whole lot of trouble.”

It was just a matter of minutes before the wildfire reached them. Gray and her husband scrambled for clothes and the contents of their safe. They stuffed everything they could into a duffle bag, loaded their young daughter and dogs into the car, and sped away. In the rearview mirror was an orange glow and the home where their toddler had recently taken her tentative first steps.

The fires that ripped across the county incinerated thousands of structures, including Gray’s home. The National Guard arrived and kept residents at a distance for two weeks. Gray and her family hunkered down with friends. Then, “the second we heard we could get back in,” she says, “we drove out there.”

They arrived to find “pure devastation on our property,” she says. “Just ashes and rubble.” The fire had consumed roughly 90 of the 125 homes in their neighborhood. The trees still standing were scorched bare. Chimneys towered over the charred husks of homes.

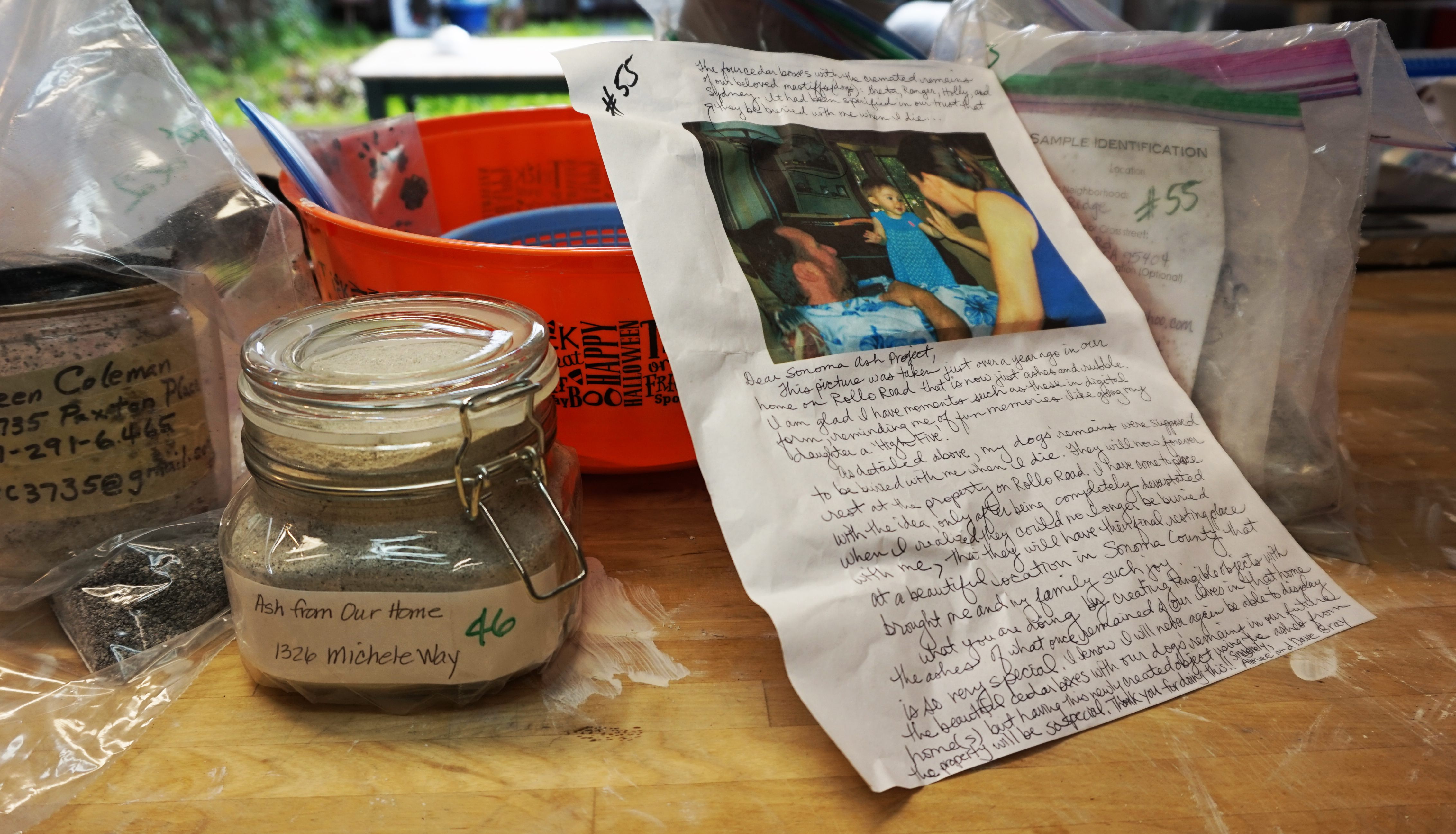

Gray could discern the footprint of her home’s foundation. Brighton’s metal dog gate was visible, too. She picked her way through the wreckage until she reached what had been their family room, where she had kept cremated remains of her four beloved other dogs—Greta, Ranger, Holly, and Sydney—in cedar boxes. Gray had planned to be buried with those ashes; it was even written into the family’s will. She pulled on a mask and gloves, stooped down, and scooped a few handfuls of ash into a plastic bag. Then she hopped back in the car, drove five minutes to the home of Gregory Roberts, and left the bag on his porch.

Roberts, a ceramicist and professor of studio art at nearby Sonoma State University, had been thinking a lot about ash. When the fires descended in October, he had had a little more warning. As they encircled his community, Roberts hosed down his roof, pulled leaves from the gutters, and did everything he could to prevent a drifting ember from finding purchase. Smoke hung thick in the air and ash tumbled down, he says, “like a really light snowfall.”

Roberts’s house survived, but when he returned to his office a week after the blazes had been controlled, he was still unnerved.

Through his ceramics practice, Roberts had experience with ash, which can be used as the foundation of a glaze. He began to think about the idea of making art with the ashes from the wildfires, but felt a little timid about the concept. Was it in poor taste to request the smoldering remains of people’s lives? “It’s a very strange ask to make of somebody,” he says.

But he found his neighbors surprisingly receptive, so he launched the Sonoma Ash Project and invited them to bring him small samples of ash salvaged from the sites of their homes. He promoted the project on Facebook, and some local clergy took up the cause. So far, more than 125 people, including Aimee Gray, have shared a scoop of ash with him.

Some samples arrive in mason jars, others in plastic baggies like Gray’s. All are deposited in a bin on the porch, and many are labeled with tape and permanent marker: names, phone numbers, addresses. A few of the samples look smooth, almost silky, like fine beach sand. Others are coarse, like freshly ground pepper. The colors range from silvery-white to charcoal—possibly a hint about what that particular flame had devoured.

No one rings the doorbell or stops to chat, but the handoffs aren’t entirely anonymous, either. Many people fasten notes or photos to their deliveries. “People want to communicate to me what these ashes mean to them,” Roberts says.

Some notes contain memories of the fires, while others describe all that was lost. Many people tried to reconcile mental maps of their homes with the charred remains. A few explained how they sifted the ash of specific parts of their homes—a shelf that displayed especially prized possessions, the corner that held a father’s dogeared library, Gray’s cedar boxes.

In thick, swirling scrawl, one person described being hauled to safety by the highway patrol early in the morning, after having watched nine houses burn. Between the narrow lines of yellow legal paper, another writer tried to make sense of how decades became ashes so quickly, something that could just blow away. “We have spent hours sifting through our rubble, only to discover there is nothing left,” wrote someone who lost a home of 40 years. “We slowly are coming to grips with the concept of forever gone.”

Gray had seen Roberts’s request on Facebook, and was eager to participate. To her sample, she attached a letter she had written describing how heartbroken she was to lose her dogs’ remains. She included a family photo snapped just over a year before, her young daughter reaching out for a high-five, dappled sunlight flooding in through the windows. With a black pen she had circled, in the background, those four cedar boxes. Though her family is intact, safe and unharmed, the fire left much to mourn.

When he receives a sample, Roberts sifts out any rocks, coins, or nails. Then he soaks the ash in water to strip out the lime, then dries it and grinds it into a fine, uniform powder. He assigns each sample a number that corresponds to the home address. It’s a practical choice, but also a poignant one. He’s created an incidental geography of loss.

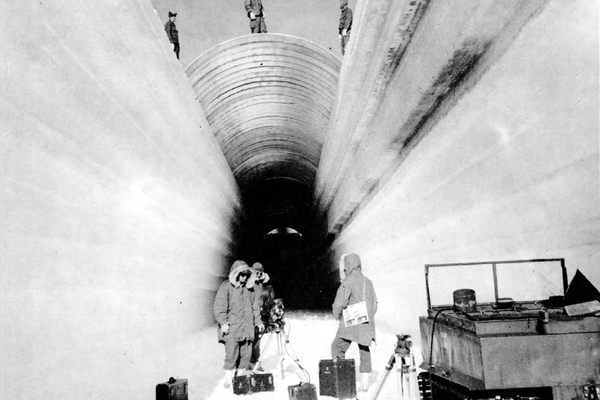

His goal is to gift each each former homeowner a piece of pottery glazed with the ashes they saved. In design, each piece will be an homage to the Fountaingrove Round Barn, a local fixture that was a casualty of the fire. The 118-year-old architectural oddity had been empty for decades, after talk of turning it into a pub had stalled. Though unused, it was an affable fixture of the landscape and a visual reference for tourists—a literal and figurative centerpiece of the community.

Gray isn’t sure where she’ll put her glazed barn when she gets it. Life isn’t back to normal—the rental home is a place for resting, not nesting. “We’re not necessarily going to get settled in here. This isn’t our forever home,” Gray says. Wherever they end up, she adds, that glazed structure, standing in the stead of her old mementos, “will be in a prominent place.”

Roberts imagines the project as precisely that sort of bridge between tragedy and what comes next. He doesn’t want to get too saccharine, he says, but “there’s a cosmic quality to it.” With a color wash, the past is transformed and kept current, just with a different arrangement of molecules. It’s a theme that at least one letter-writer saw, too. The pottery will serve as something tangible—even beautiful—“that we can put to use in the life ahead.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook