The Reclaiming of the Shrew

A biologist solves the mystery of two dozen missing animal mummies.

The other day I was checking my email and was excited to see a note from Neal Woodman. Woodman is a research biologist and curator of mammals at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., and every time he gets in touch he has something interesting to say.

The first time we talked, he told me about the Mystery of the Mule Deer, which involved an apocryphal journal and one very eccentric naturalist. He also hinted that he had discovered the full extent of a famous historic prank. The next time I heard from him, he revealed the details: John James Audubon, of avian illustration fame, had invented at least 28 fake species of fish, snails, birds, rats, mollusks, and plants to play a joke on a rival.

The thread that connected these stories was shrews, small, pointy-nosed mammals that can be found around the world. Woodman is a shrew guy, and his specialty leads him down winding paths to obscure, intriguing stories. I knew I would not be disappointed by the work he was ready to talk about now—his hunt for a set of missing Egyptian shrew mummies.

For Woodman, the hunt for the missing shrew mummies began while he was working out the taxonomic history of the sacred shrew, Crocidura religiosa, otherwise known as the Egyptian pygmy shrew. Compared to more common European shrews, the sacred shrew is on the small side, with a notably long and squarish tail. The first time modern naturalists ever encountered this species, it was as a black, shriveled mummy.

In 1826, an Italian archaeologist, Joseph Passalacqua, went to Paris with the bounty he’d taken from an excavation near Thebes, Egypt—figurines of wax, limestone, and enameled clay; jade, lapis, and amethyst jewels; musical instruments, combs, and games; works in bronze, gold, and silver. Among the more than 1,900 items Passalacqua brought to France were scores of mummified animals, from crocodiles and cats to owls and ibises, including more than two dozen mummified shrews.

In ancient Egypt, priests created animal mummies as messengers to the gods, which were then bought by worshippers as votive offerings. The animal’s soul, it was believed, would carry the petitioner’s pleas to the spirit world. Archaeologists found rooms filled with animal mummies, so many that at one point, they were treated as trash, used for ballast, and tossed on French fields as fertilizer. Shrew mummies, thought to be connected to the falcon-headed god Horus, were a common variety.

In Paris, a French naturalist, Isidore Geoffrey Saint-Hilaire, examined the embalmed shrew remains that Passalacqua had brought and identified the long-dead shrews as a new species. (Later his initial finding was confirmed. In fact, sacred shrews are still around in Egypt today.) He described the sacred shrew in a few different documents and, originally, Woodman’s interest was in determining which take should be given priority.

“It was one of these anal-compulsive details that guys like me think is really crucial,” he says. But soon he was preoccupied with a different detail. At some point before 1968, the mummy shrews that had been used to name the species had disappeared.

“I kept thinking, ‘What had happened to the mummies?’” Woodman says. “They were in Paris, for God’s sake. It was the place to be for knowledge and research. Alexander von Humboldt was hanging out in Paris. That’s where all the educated people were. What happened? Why aren’t they in a French museum?”

He decided to find out.

For taxonomists and others who care about accurate descriptions of the natural world, the first members of a species ever identified—the “type series”—are critical scientific objects, references that show how and why someone thought they qualified as a unique species. The specimens mark the beginning of human knowledge of a particular type of plant or animal, and if they’re lost it’s impossible to see exactly what that first scientist did.

It happens all the time: A type series might be damaged by pests, misused, or thrown away. In this case, though, there was no record of how the mummy shrews had met their end. Although the mummies were officially declared lost in 1968, as early as 1827, Saint-Hilaire lamented that “all that remains to us today of the shrews from Thebes” was his illustrations.

Even if the shrew mummies were gone forever, Woodman wanted to know what happened to them.

As he started his research, he came across the catalogue that Passalacqua made for his Egyptian discoveries and began to think about how the shrew mummies weren’t typical taxonomic specimens, which are collected by naturalists or biologists. Usually, taxonomic specimens would have been preserved in a natural history collection, but these were considered archaeological specimens. So, he wondered, what had happened to the rest of Passalacqua’s finds?

Passalacqua hadn’t gone to Egypt just for scientific glory. The artifacts he brought back from Egypt were assets, ones that he soon put up for sale. The French government had no interest in the collection, but the renowned naturalist Humboldt was familiar with it and convinced Friedrich Wilhelm IV, the crown prince of Prussia, to buy the whole lot. Both the artifacts and Passalacqua, hired as the director of the new Royal Museums, went to Berlin.

The trail was easy enough to follow from there. In 1850, the Prussian crown’s entire Egyptian collection moved to the Neues Museum, where it remained until World War II, when the museum was damaged and the collection was divided between East and West Germany. In 1991, after reunification, the scattered Egyptian artifacts, including the Passalacqua collection, were reassembled as part of Berlin’s Egyptian Museum.

Woodman e-mailed the museum to ask if they might still have the shrew mummies in the collection. Finally, he received an answer—“Oh, yes, we have them.”

“We had been looking in the wrong place because we’re biologists,” says Woodman. For decades, scientists interested in the shrews had assumed the original specimens were lost, because they were expecting to find them in a natural history collection. They hadn’t thought to look in other museums. It turned out that when Saint-Hilaire lamented the loss of the shrews, he was probably referring to their move to Berlin, which, Woodman writes, was then “an intellectual backwater that even Humboldt attempted to avoid.”

Today, Berlin’s Egyptian Museum is a world-class facility, which Woodman visited with his colleague and coauthor Rainer Hutterer, who works at the Alexander Koenig Research Museum in Bonn. They had rediscovered the shrews, and they wanted to have a fresh look at them.

To the layperson, there’s not much to see. “If you’re an expert, you can tell they’re shrews, but otherwise they just look like ugly blobs,” says Woodman. They’re very dry, very valuable ugly blobs, though, so they have to be handled carefully.

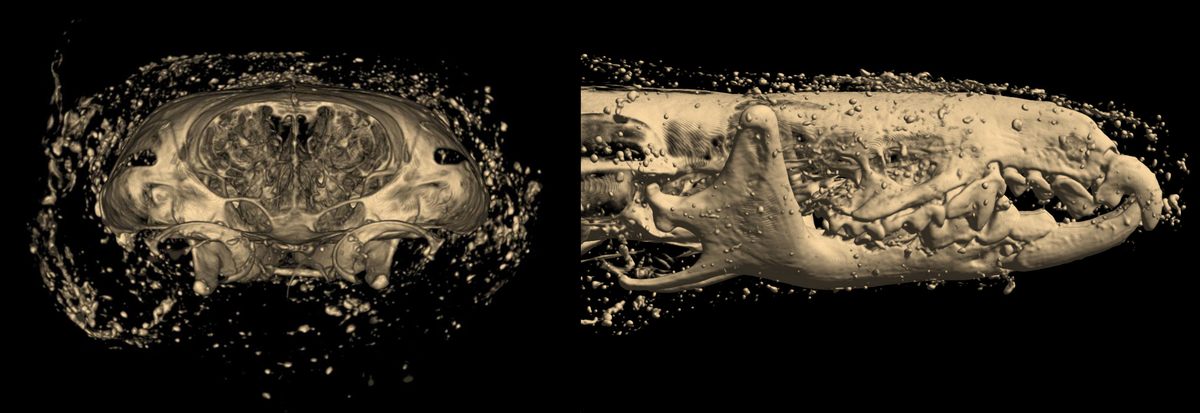

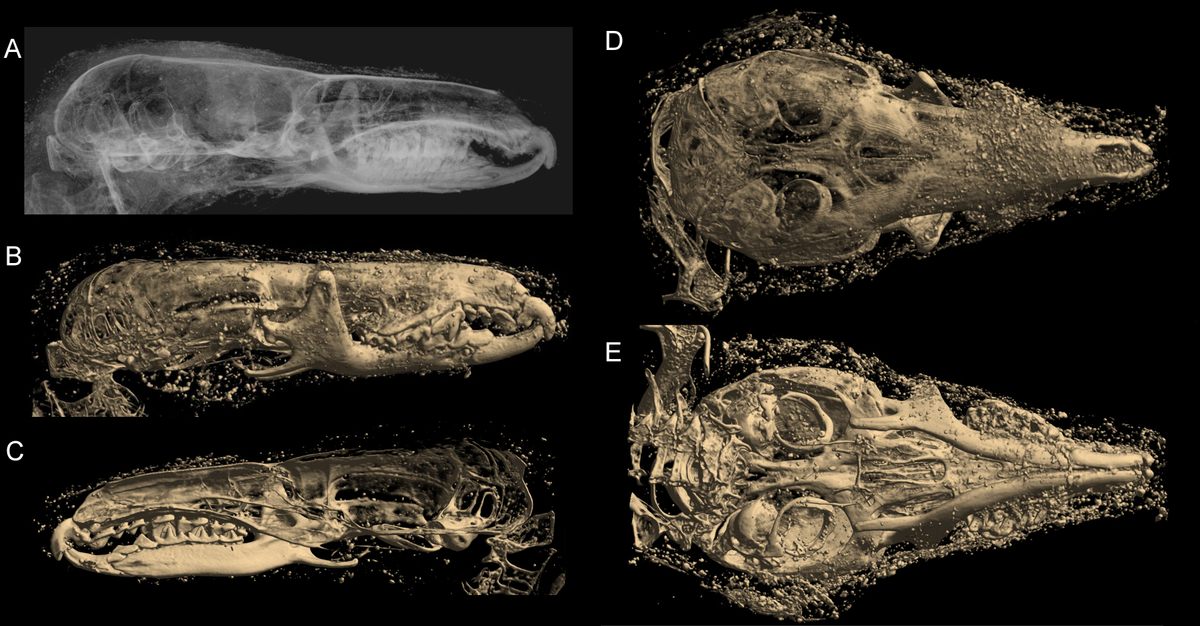

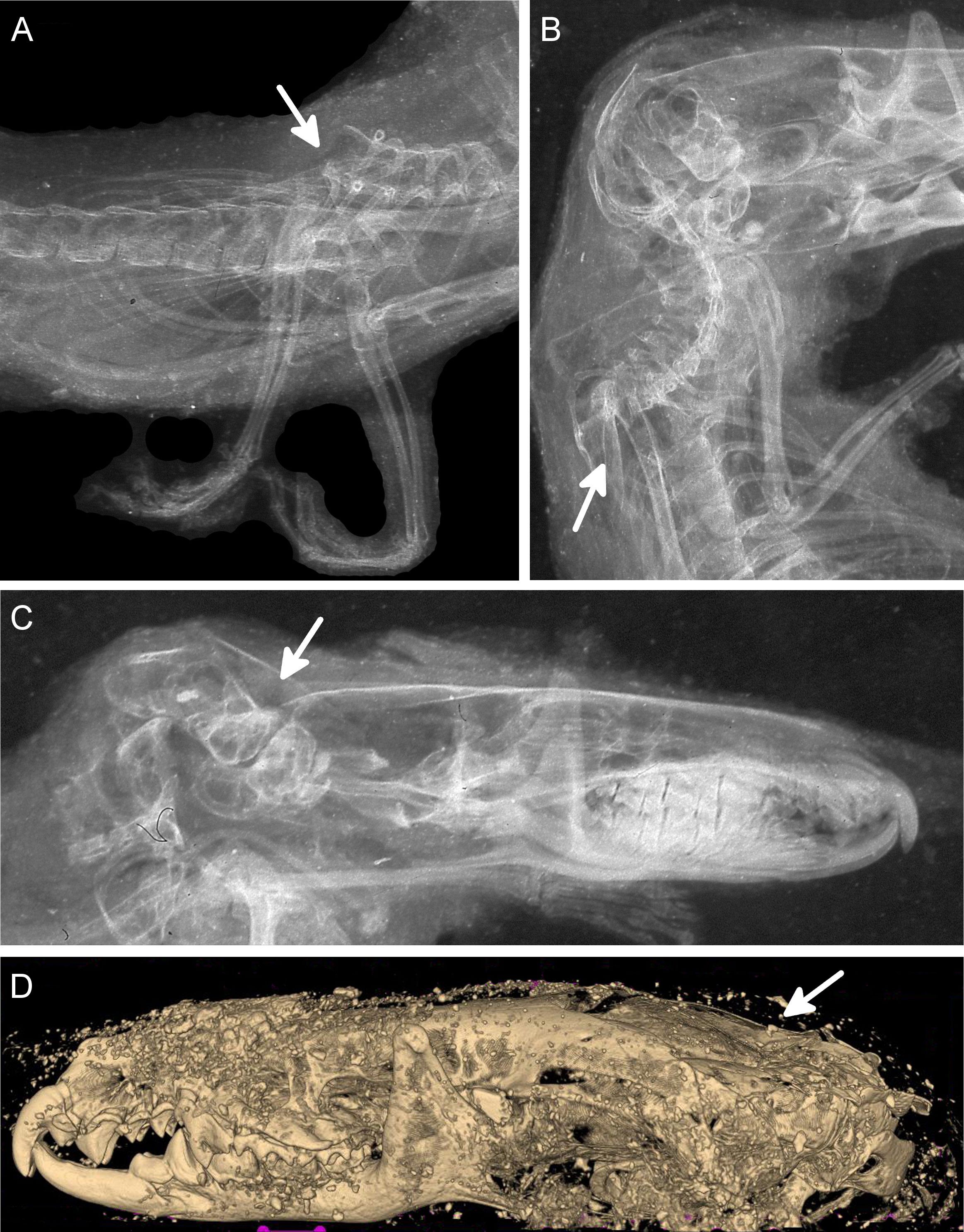

Since the Passalacqua collection came to Berlin, some of the original mummy shrews were indeed lost, likely in the turmoil of the 20th century. But 19 remain. By measuring and examining the specimens, and looking inside using X-rays and microCT scans, Woodman and Hutterer were able to pick a new lectotype—the single best example of the original specimens, which will serve as the primary taxonomic model for the species—and redescribe it in the context of modern shrew knowledge.

While the scientists examined the collection, though, Hutterer noticed that two of specimens didn’t fit the description of the sacred shrew. They were even smaller, with hind feet just a quarter of an inch long—a new species of shrew, never before documented in Egypt, named Crocidura pasha.* The results of their work have now been published in the journal Zootaxa, and, barring any further historical misunderstanding, future scientist should know just where to find the type specimen. The mystery of the mummy shrews was laid to rest.

*Correction: This article originally reported that Crocidura pasha was a newly discovered species, but it is only newly discovered in this particular part of the world.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook