The Secrets of the White House Reflect Its History of Constancy and Change

A sturdy desk, an empty pool, and—maybe—secret passages.

For more than two centuries, the White House has stood as a symbol of democracy and resilience in the face of change—a symbolism that carries particular poignance following the turmoil of the 2020 election and its aftermath. The stories embedded in its decor, artwork, hallways, and chambers capture colorful moments and occasional upheavals in American history. Known as the “Executive Mansion” or “President’s House” during its first century, the building has been burned, rebuilt, shored up (after a tinkling chandelier warned of some structural instability), renovated, and expanded into the complex we know today.

John Adams was the first resident of the house in 1800 (George Washington lived in Philadelphia most of his presidency, while staying heavily involved in the design and construction of the new federal home). Thomas Jefferson had his office in what is now part of the State Dining Room. In 1886 Grover Cleveland was married in the Blue Room, the same space where James Monroe had tea and cake with Native American leaders from the Great Plains some six decades earlier.

Under Chester A. Arthur, the White House was a trove of Louis Comfort Tiffany decor (a magnificent colored-glass screen that the famed designer made for the entrance hall is one of many relics lost to history). Then, in 1902, Theodore Roosevelt ordered a complete renovation by McKim, Mead & White that created the West Wing and compound as it mostly stands today. He also officially christened it the “White House.”

Throughout shifting eras and presidents, the essence of the White House and its mission have endured, even if the trappings change. President Biden has placed a portrait of Franklin D. Roosevelt above the Oval Office mantel, and brought in other historic portraits and busts that signal his vision for the country. He has, of course, kept the storied Resolute Desk, hewn from the timbers of a 19th-century British exploration ship. Its unique history and other unusual aspects of the White House offer a peek at how the working residence embodies both consistency and change.

Steady as She Goes

Gifted by Queen Victoria in 1880, the Resolute Desk has been used in some capacity by most presidents since Rutherford B. Hayes. The half-ton desk is constructed of oak timbers from HMS Resolute. Specially fitted for Arctic exploration, the ship was part of an expedition sent in 1852 to search for lost explorer Sir John Franklin, who perished along with more than 100 men in an ill-fated quest to find the Northwest Passage. Resolute was abandoned and, three years later, found drifting among ice floes in the Davis Strait by an American whaler. She was refitted and sent back to England with great fanfare. A portion of her timbers returned to America decades later as the Queen’s heavyweight gift to President Hayes. John F. Kennedy was the first to install it in the Oval Office.

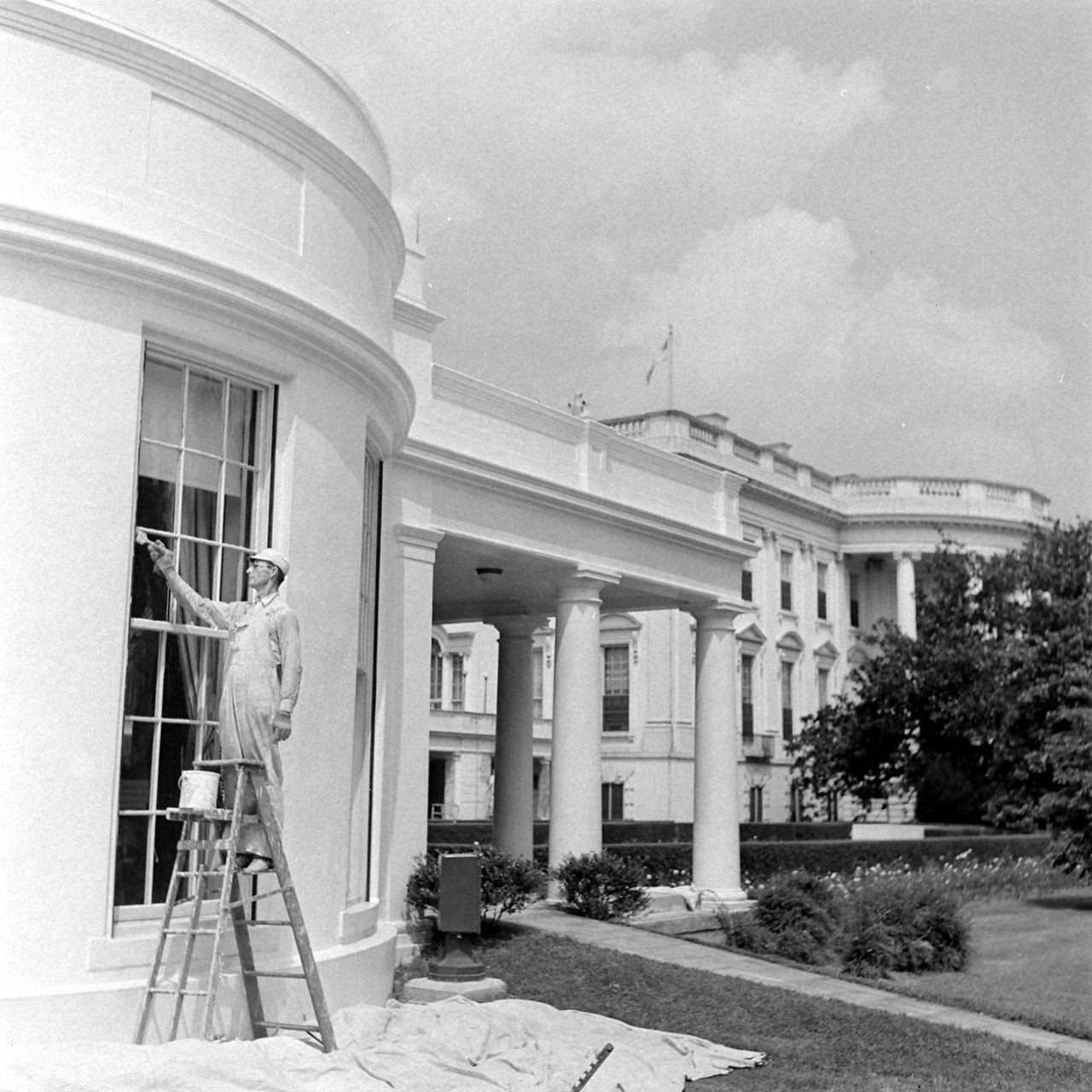

It’s Not Actually White

Built of locally sourced sandstone, the White House is, in fact, off-gray, says Matthew Costello, senior historian at the White House Historical Association. To protect the porous stone from the elements, stonemasons whitewashed the house in 1798, making it a bit lighter. The bright white of lead-based paint arrived in 1818, four years after the British burned down the original house. Over time, so many layers of paint accumulated that it took 16 years to strip them all off in a major restoration project that concluded in 1996. Each layer requires 570 gallons of paint.

Ten Pin Under the North Portico

Even presidents need to have fun. The White House bowling alley started with Harry Truman, who had two lanes installed in the basement in 1947. And though he wasn’t much of a bowler, he allowed the White House staff to create a bowling league, says Costello. Dwight Eisenhower found more practical purposes for the space when he took office in the 1950s, and converted it into a central filing and communications room, while Truman’s bowling alley was dismantled and reassembled across the street, under the giant structure now called the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

Then came Richard Nixon. “He liked to bowl late at night, especially to take his mind off things,” says Costello. Eventually it was deemed necessary to construct a private, single bowling lane just for him in the White House itself, under the North Portico, where it remains today.

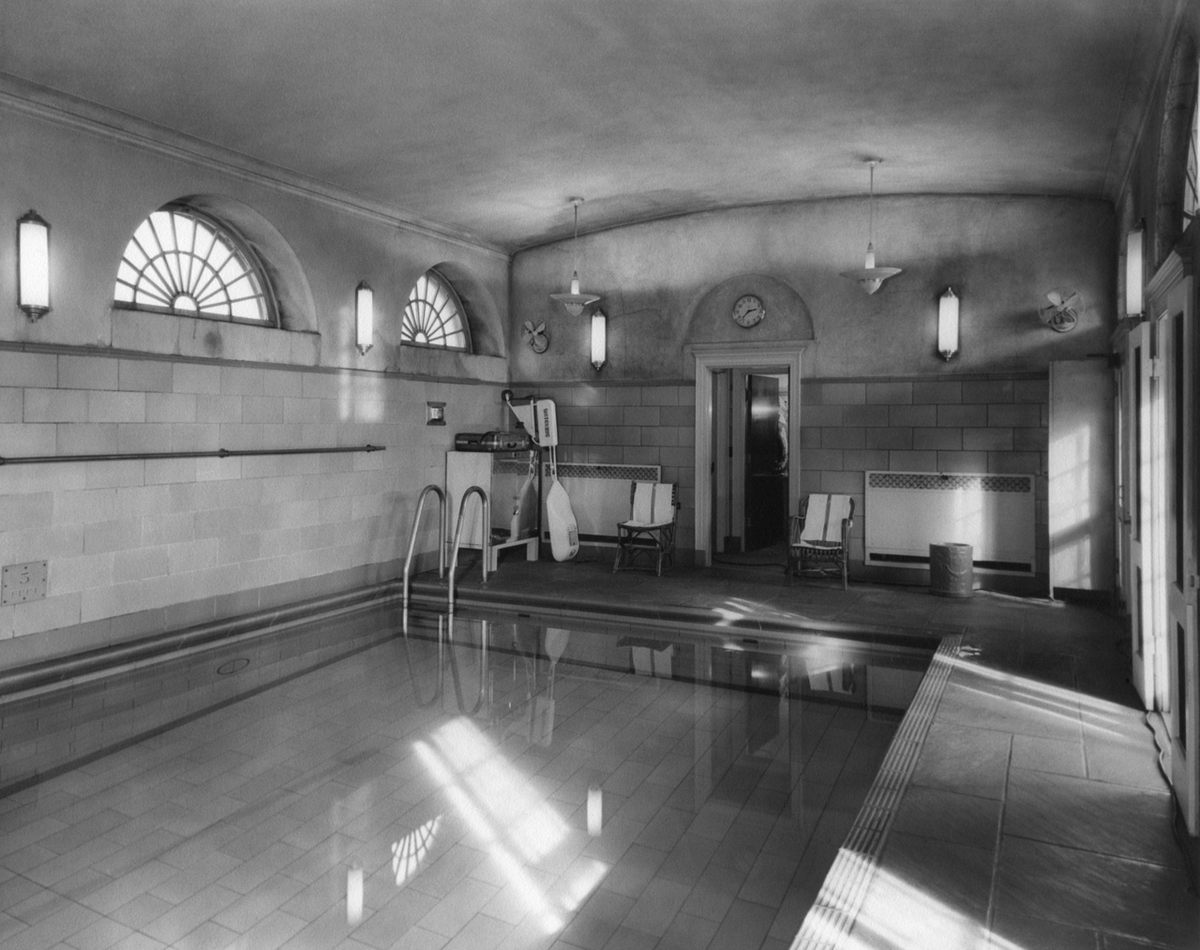

The Real Press Pool

All good things must come to an end. Just as the space with Truman’s bowling alley evolved into what is today’s Situation Room, so an indoor pool built for polio-afflicted Franklin D. Roosevelt now sits under one of the less glamorous but hugely important spaces in the White House: the Press Briefing Room.

“It will probably never be used as a pool again,” says Costello. But that hasn’t stopped the curious from checking it out. At one point, a trap door with a steel ladder near the presidential podium led to the decommissioned pool; now a separate staircase does the job. “It’s become like a tradition,” he adds. “Members of the White House staff and press corps will sign their names on the pool tiles. Some people say you can still smell the chlorine.”

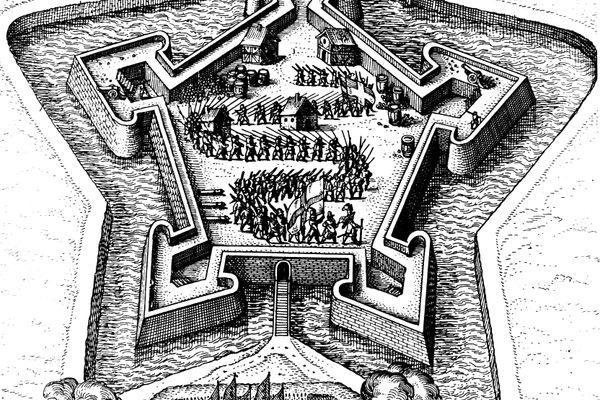

The Portrait Saved From the British

Very few items survive from the White House before 1814, when British troops set it ablaze, along with the Capitol, following their victory at the Battle of Bladensburg during the War of 1812. One of the sole survivors is Gilbert Stuart’s iconic 1797 portrait of George Washington, which First Lady Dolley Madison famously ordered to be saved before she fled. The group that rescued the portrait—breaking the frame to carry out the canvas—included an enslaved man named Paul Jennings and an Irish gardener, who “put it on a wagon and got it out of the city,” says Costello. The full-length portrait was returned to the rebuilt mansion in 1817 and now hangs in the East Room.

And, Finally, the Secret Passageways

So, are there any? “Yes and no,” Costello replies coyly. “Obviously I can only talk about the ones that are public knowledge.” That includes an underground command center—officially the President’s Emergency Operations Center—that was glimpsed in pictures, released in 2015, of George W. Bush and senior staff on 9/11. Its origins lie in a bomb shelter that was built below the White House following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. As for historic rumors that surfaced about secret tunnels for Abraham Lincoln—those, says Costello, have been debunked.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook