Solving the Mystery of the Seated Man

This rare portrait can now be credited to Harlem Renaissance artist Richmond Barthé.

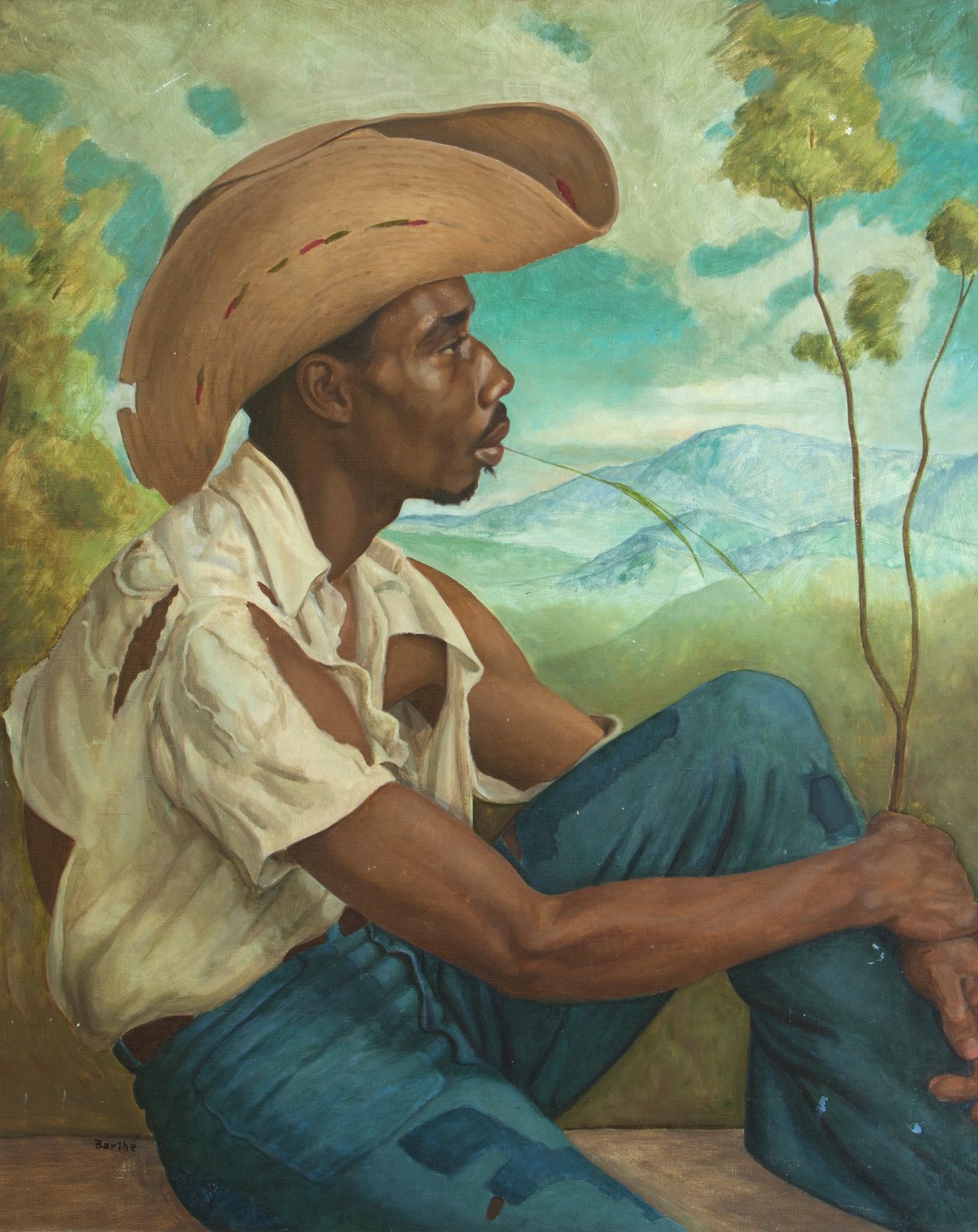

In a 17th-century castle called Belton House just outside of the town of Grantham in Lincolnshire, England, there’s a mysterious painting of a black man in profile. He’s wearing a straw hat, a torn white shirt, with his arms resting on his left leg. Seated in front of what looks to be a landscape painting, the model looks relaxed, perhaps even bored. At the bottom of the portrait, there is a signature that has long baffled art historians. “The original catalog record had transcribed the signature as B-E-R-T-H-E,” says Alice Rylance-Watson, the assistant national curator for pictures and sculptures at the National Trust UK, the largest conservation charity in Europe. “I didn’t find that name in any index of artists.” The identity of the subject and the artist remained a mystery–until now.

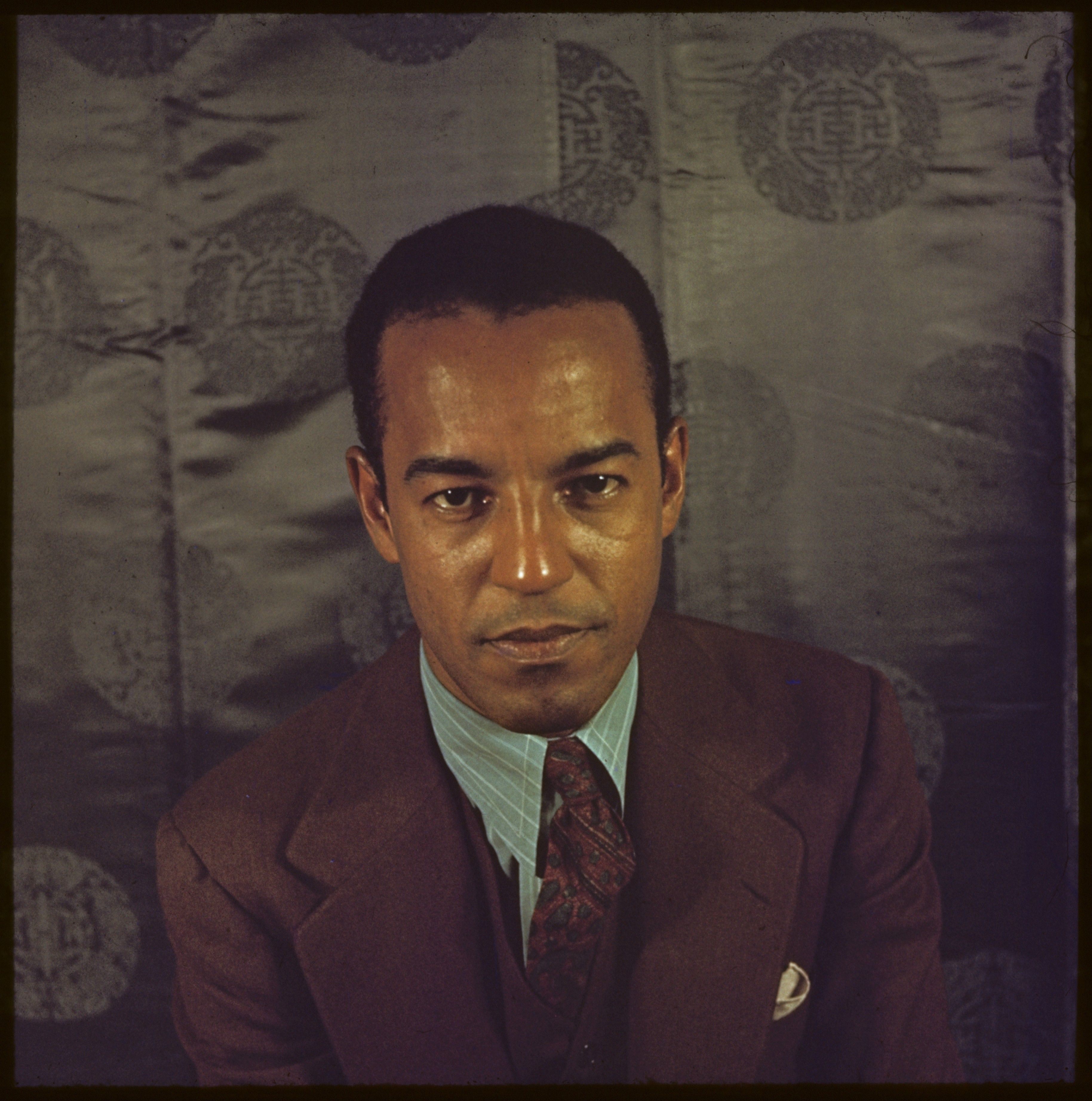

In 2020, Rylance-Watson was working on cataloging works created for and by marginalized people, when this portrait attracted her attention in an online catalog because a large proportion of black portrait subjects appear in paintings from the 17th and 18th centuries, while this painting looked to be from the 20th century. When Covid lockdown restrictions were lifted in October 2021, and she had the opportunity to visit the Belton House, Rylance-Watson transcribed the signature herself: B-A-R-T-H-E. There had been a typo in the catalog. With this new information and the help of the research done by the late art historian Margaret Rose Vendryes, Rylance-Watson was able to attribute the painting to Harlem Renaissance artist Richmond Barthé.

Born James Richmond Barthé in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, Barthé is best known as a sculptor, although he first went to art school intending to study painting. “He showed such talent and skill and artistry in the plastic arts that he was heavily encouraged to reorientate towards that,” says Rylance-Watson. In her extensively researched book, Barthé: A Life in Sculpture, Vendryes wrote that since Barthé was one of the few African-American artists recognized by the mainstream art world during his lifetime, it is surprising that so little is known about him today. Indeed, the discovery of this portrait, called Seated Man in a Landscape, only further emphasizes that fact.

Curators at the National Trust UK say the portrait was created in the 1950s, during the decade that Barthé spent living in Jamaica. “After 20 years in New York, he became disenchanted with the American art world,” Rylance-Watson says. Barthé was looking for a new start in Jamaica and intended to quit sculpting and focus on painting. However, Barthé’s paintings didn’t bring the same commercial success his sculptures did. He ended up giving away most of his paintings or destroying them. Seated Man is a rare survivor and glimpse into that lesser-known period of Barthé’s life and work.

Rylance-Watson was also able to identify the subject of the portrait. By comparing the painted face to those sculpted by Barthé and to a photograph that Vendryes published in her book, Rylance-Watson discovered the model was Lucien Levers, part of Barthé’s domestic staff in Jamaica. “It was really clear that it could be no one else but Lucien Levers, because he’s got a really pronounced bump at the top of the bridge of his nose, and I saw that completely reproduced in the painting,” she says. There’s also an existing portrait of Levers in the guise of Othello that Barthé drew, and he is the subject of two of the artist’s sculptures, The Meditation and The Dreamer.

So how did Seated Man in a Landscape find its way to England? The National Trust is still working on figuring that out. Rylance-Watson points out that Barthé’s open studio in Jamaica was geographically close to the holiday home of Peregrine Cust, a descendent of the family that built Belton House. This connection is supported by the fact that there is a marble memorial with a bronze relief portrait of Cust’s second wife signed by Barthé on the grounds of the mansion.

According to Rylance-Watson, Seated Man is the only known painting by Barthé in a public collection. However, she believes that there may be others out there in the world.

In her 2008 book, Margaret Rose Vendryes, one of the few historians who studied Barthé’s life and work, wrote that “Barthé’s oeuvre is large and still not completely known.” Rylance-Watson hopes the discovery of Seated Man in a Landscape will change that.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook