See the Soft Aquarelle Watercolors That Resulted From Krakatoa’s Big Bang

A set of paintings show the calm, lingering aftermath of a world-shaking event.

The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa has often been described as a ferocious, earth-shattering event. It was: millions of tons of ash, superheated pyroclastic flows, city-decimating tsunamis, and the loudest sound ever documented by people.

It permanently altered the Dutch colony that would become the nation of Indonesia and in another, more subtle, way, it altered the world’s imagination. For example, months after the eruption, artists in northern Europe and North America were inspired by the vivid sunsets its stratospheric ash created.

According to The New York Times in November 1883—three months after the eruption—“Soon after five o’clock the western horizon suddenly flamed into a brilliant scarlet, which crimsoned sky and clouds. People in the streets were startled at the unwonted sight and gathered in little groups on all the corners to gaze into the west.”

The thick, miles-high ash clouds in the Indian Ocean had lost their shape and drifted into the stratosphere, thereby forcing the light of sunsets around the world through an invisible diffractor. Edvard Munch, the famously morose artist behind The Scream—which features an infernal sky (thought to have been inspired by the Krakatoa aftermath) behind its ghoulish subject—wrote that “ … the Sun set—all at once the sky became blood red … clouds like blood and tongues of fire hung above the blue-black fjord and the city [of Christiania],” and added, “I felt a great, unending scream piercing through nature.”

Volcanic eruptions have long inspired artists to try and replicate the vivid skyscapes they induce. Famed British painter J.M.W. Turner may have chronicled eruptions in his work. The Krakatoa event was captured by a later Brit, oil painter William Ascroft, who made more than 500 works trying to capture the light shows that occurred over the Thames. Across the Atlantic, Frederic Edwin Church rushed to Ontario to try to get a good view of the spectacle, for his own portfolio.

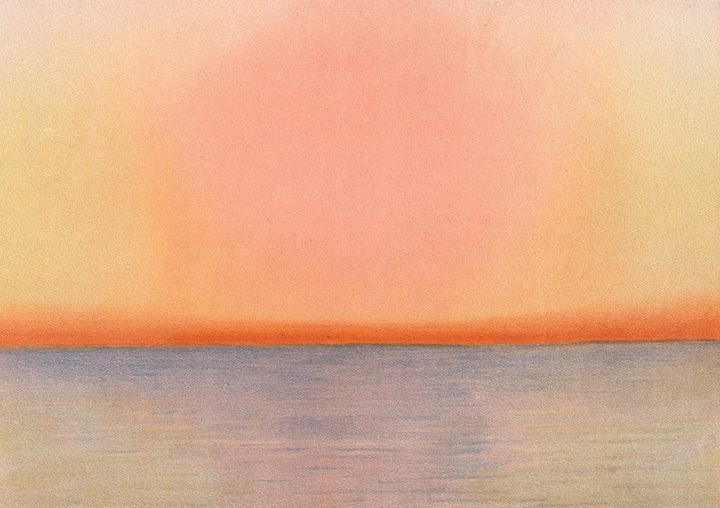

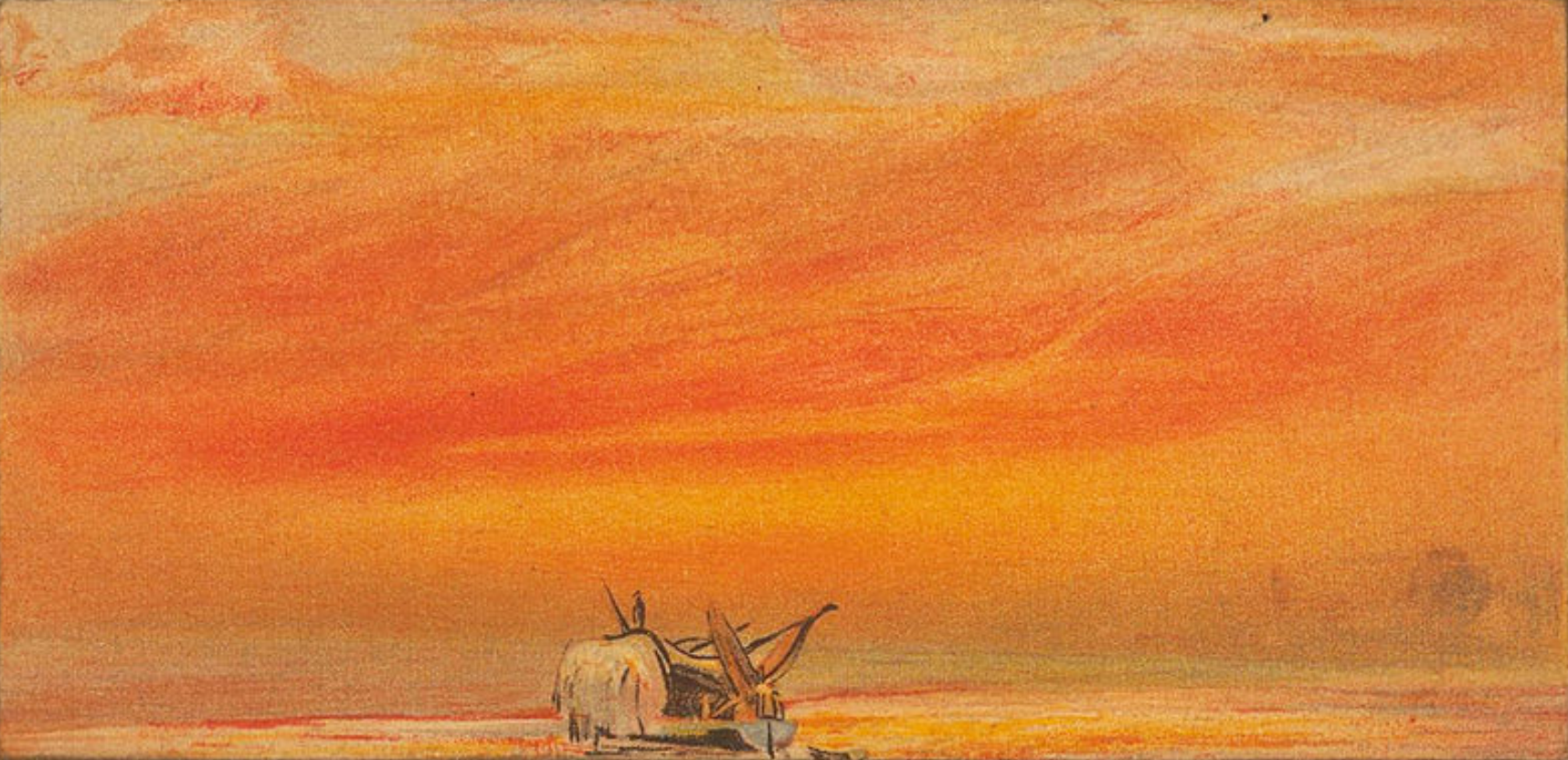

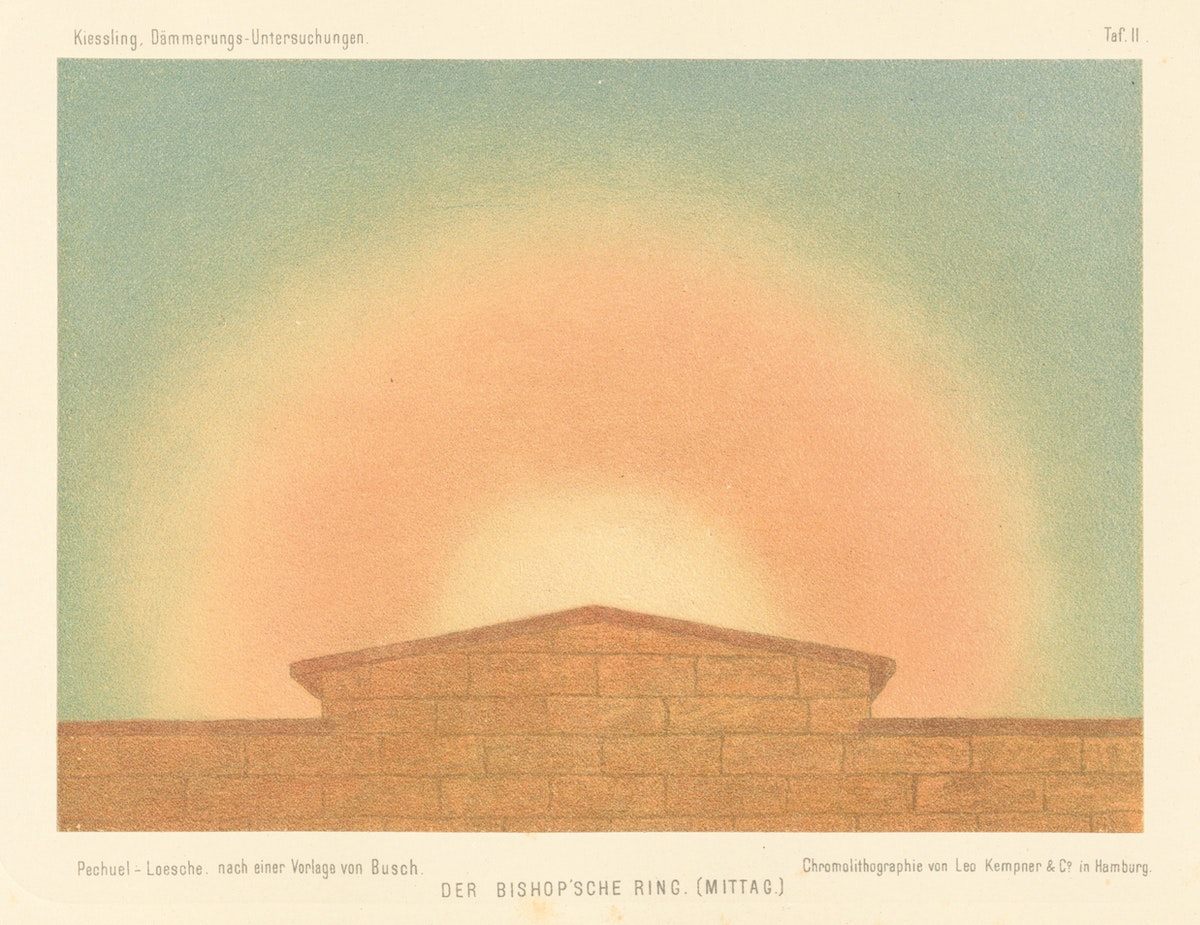

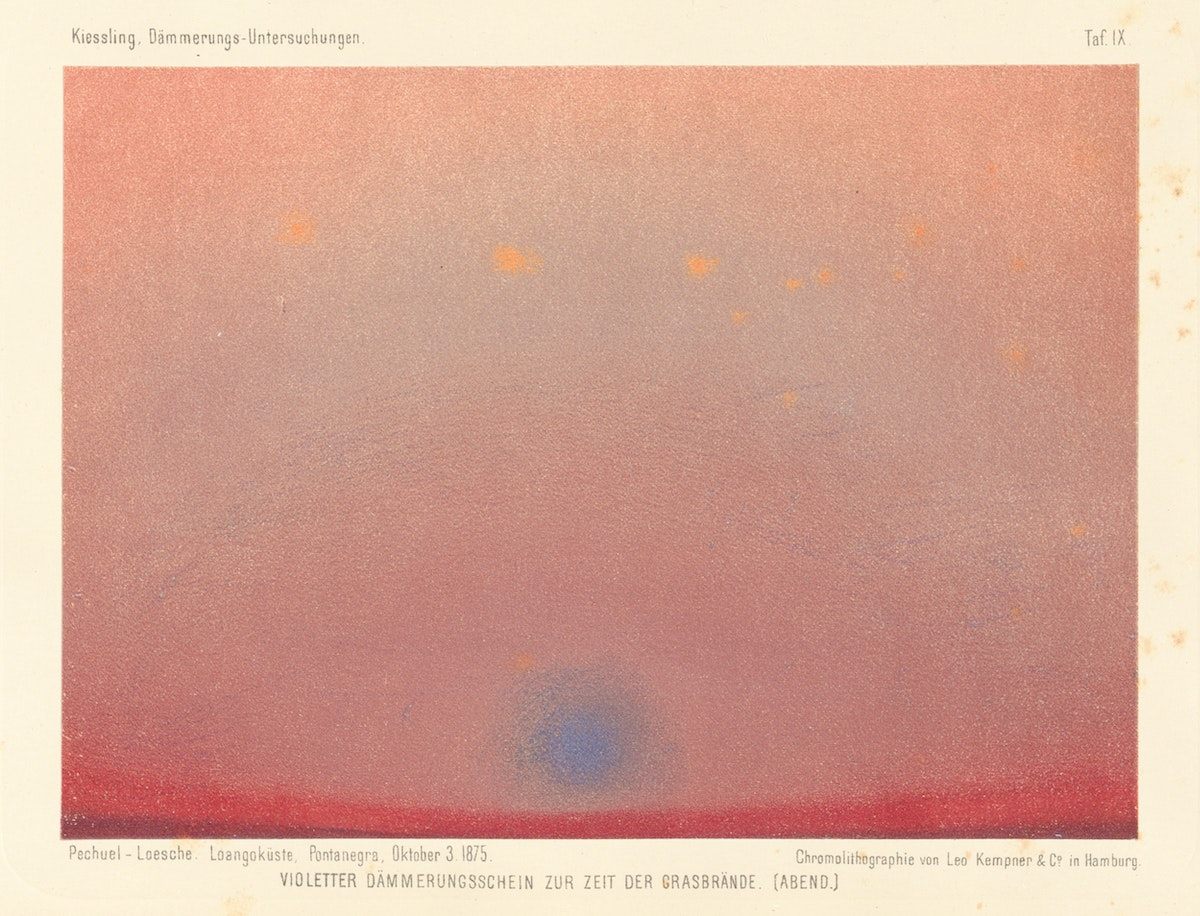

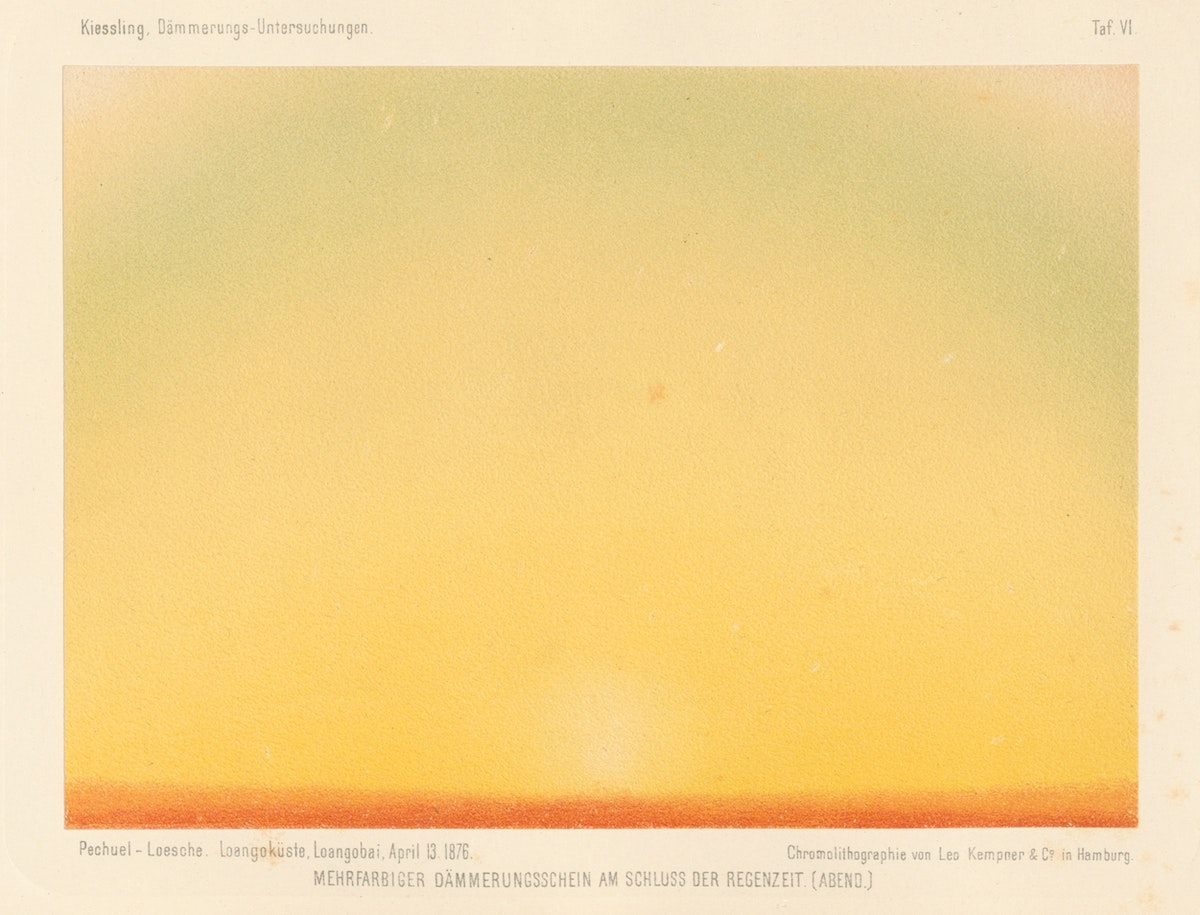

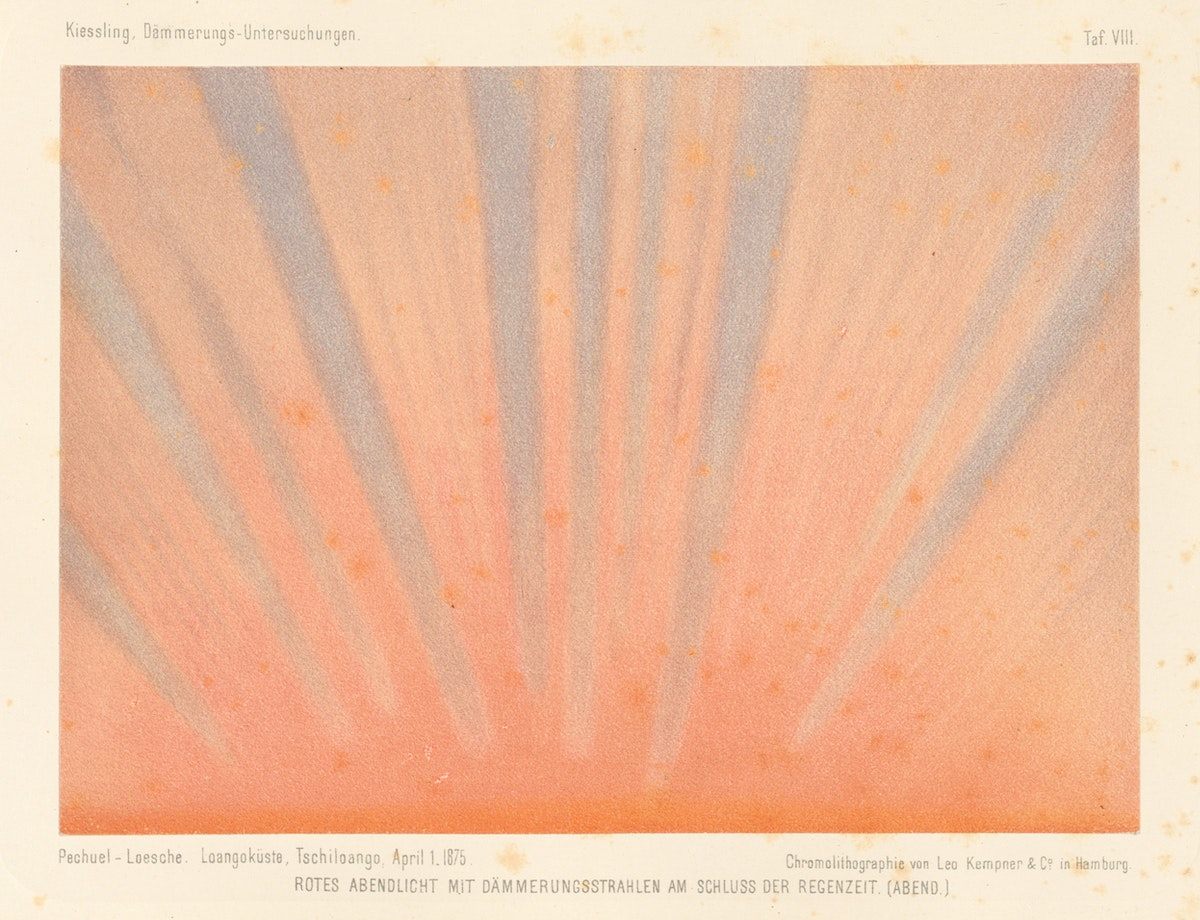

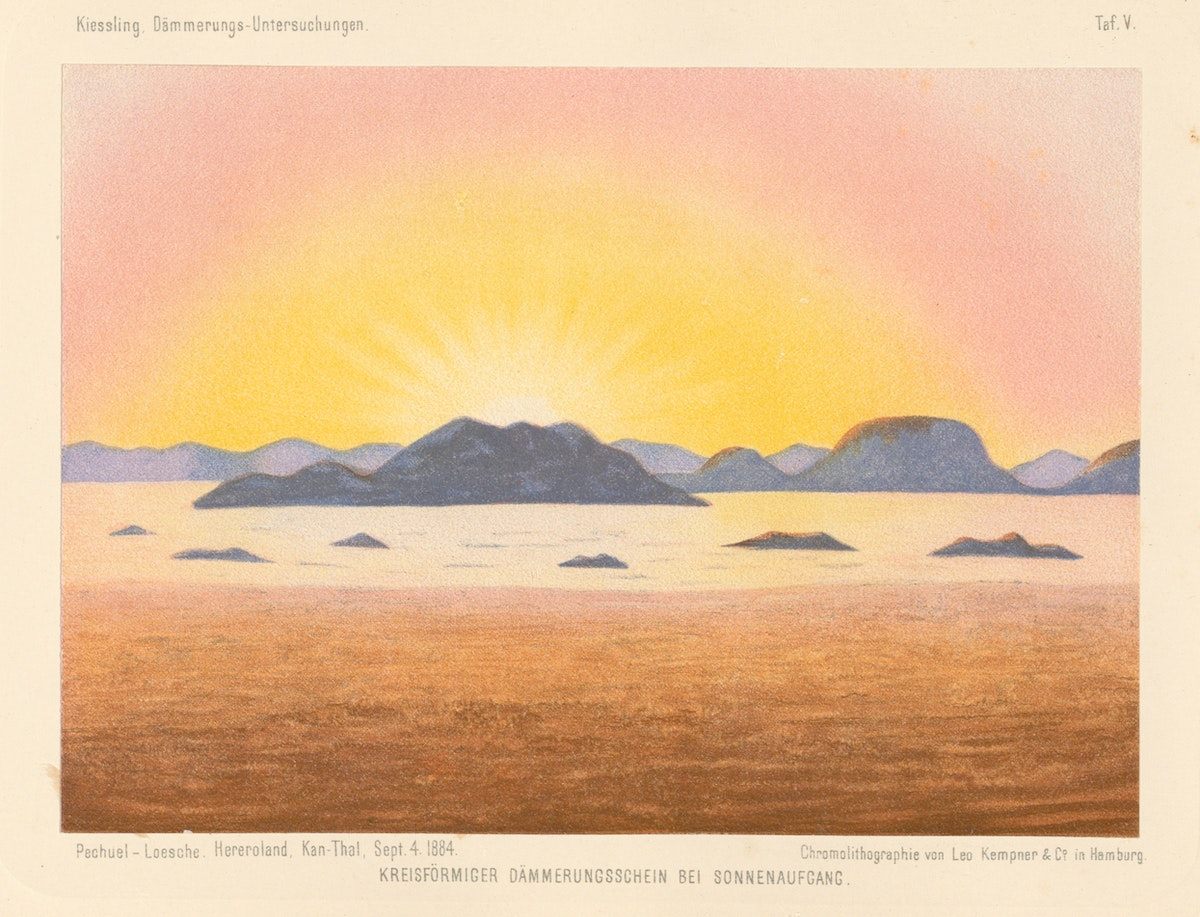

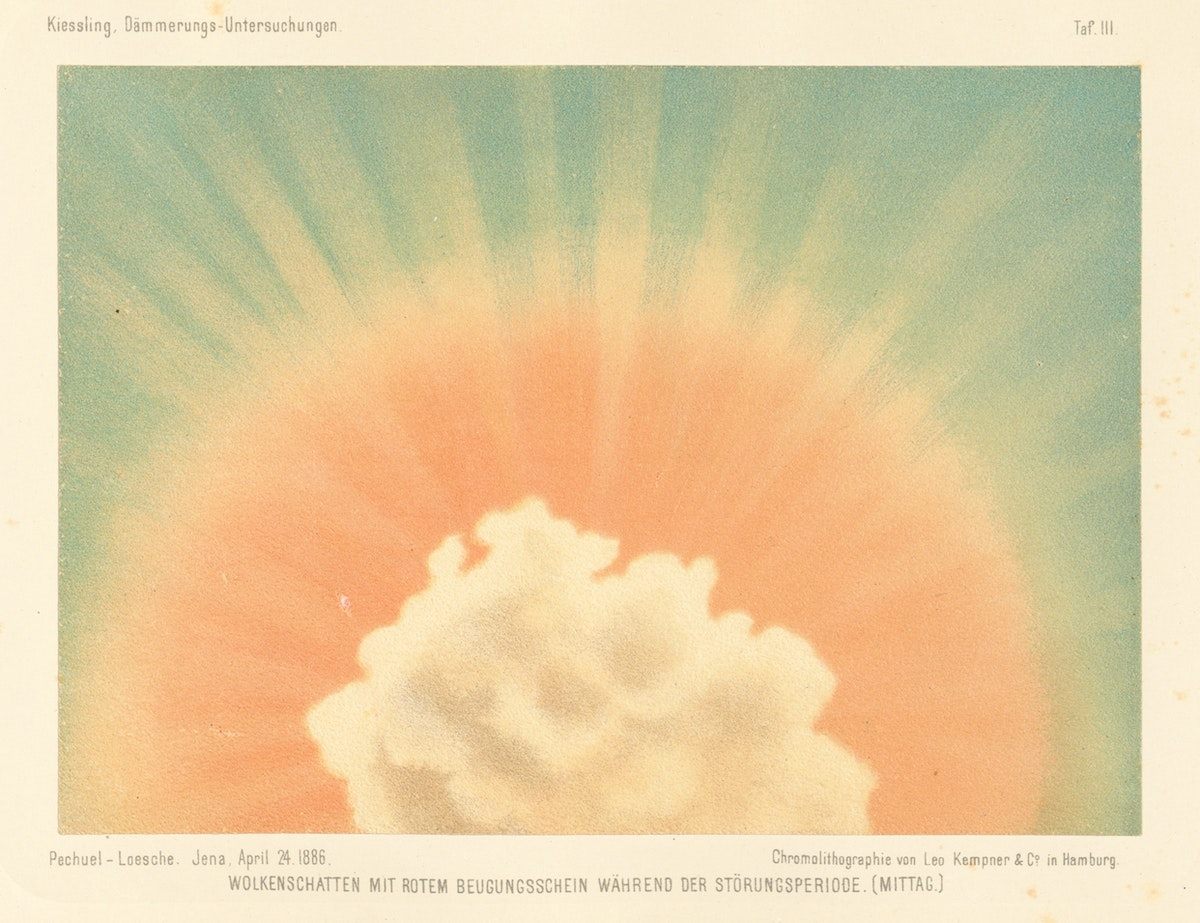

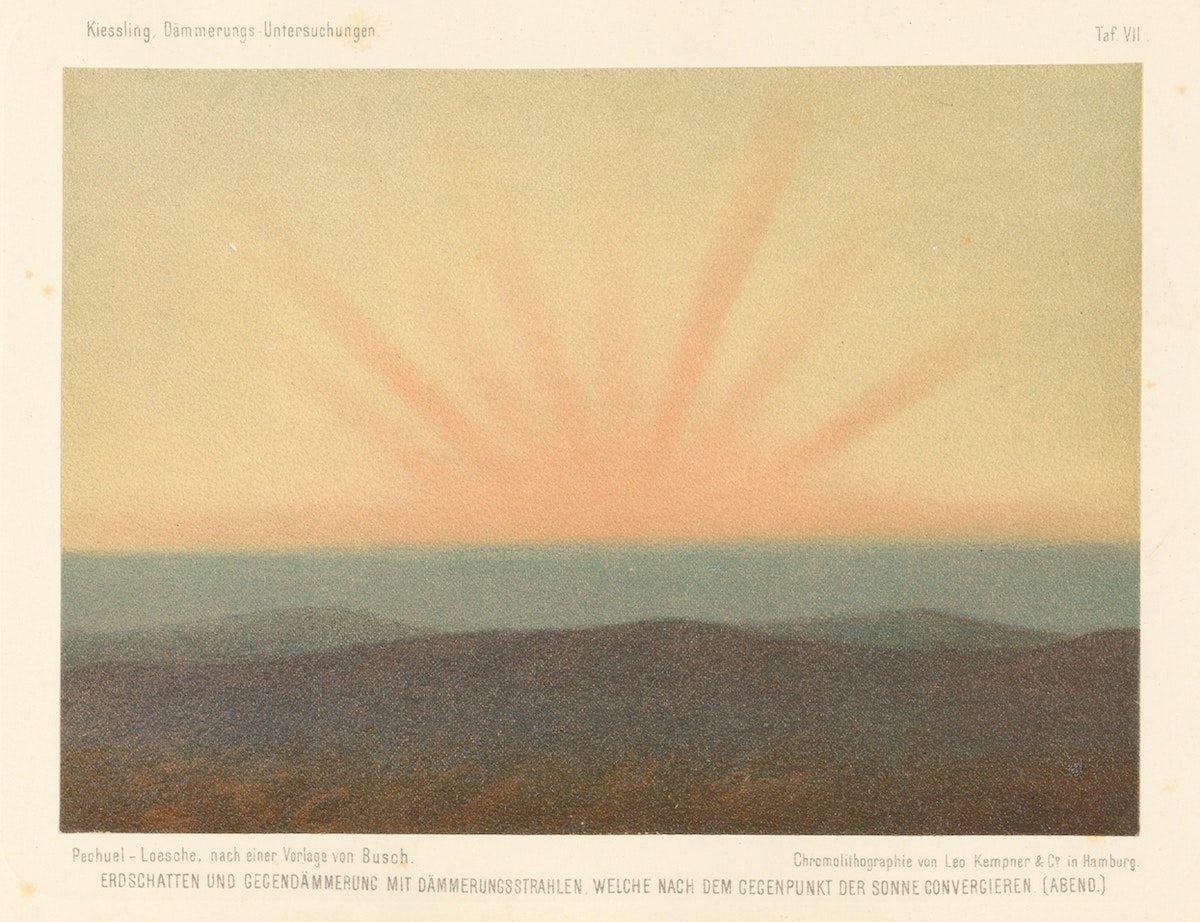

A different Edward—German naturalist and painter Eduard Pechuël-Loesche—saw something rather ethereal in the sky. His depictions of the volcanic aftermath, included at the end of a book prepared by German physicist Johann Kiessling, show off the contrast known to eyes adjusting to a new sight: muted, darkened landscapes paired with startling skies. Pechuël-Loesche’s work burns like embers, and was made with transparent watercolors, a style known as “aquarelle” that became popular in 18th- and 19th-century Europe. It is almost as though the last word on the fearsome eruption was something surreal and, perhaps, calming.

The Public Domain Review recently compiled some of Pechuël-Loesche’s images, and we have a selection here.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook