How Njoya the Great Put His African Kingdom on the Map

A representation of the Bamum kingdom is a rare example of early-20th-century indigenous African cartography.

Cartography doesn’t merely reflect the world; it shapes it, too. Maps can be used to express possession, justify aggression, and codify conquest. Take the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, for example, where Europe came together to carve up Africa into spheres of influence. Maps were used as the first, blunt instruments of colonialism.

If It’s on a Map, It Exists

Those spheres soon hardened into lines, and by the start of World War I, nearly all of Africa had been turned into European colonies. Most of those lines survive today as the borders of Africa’s independent states.

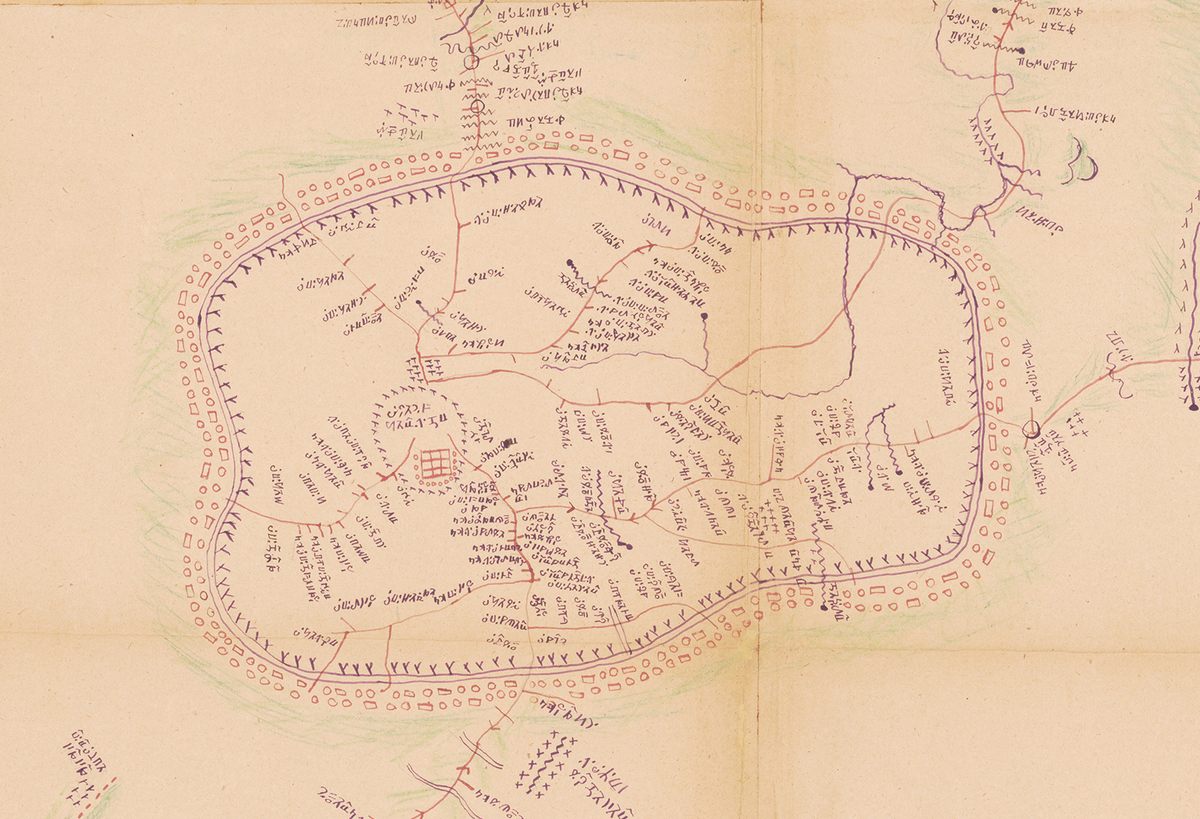

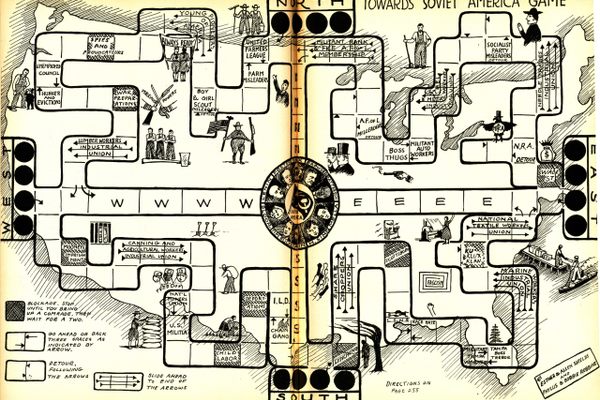

Cartography served the colonizers well in Africa. But maps work well in other hands too. This map is a fine, if rare, example of an indigenous African kingdom adopting cartography to affirm its own existence. Made in the early 20th century, it shows the villages, mountains, and river borders of Bamum (also known as Bamun or Bamoun), an ancient kingdom in what is now western Cameroon. The map is the brainchild of its remarkable king, Ibrahim Mbouombouo Njoya, now remembered as “Njoya the Great.”

Njoya’s Great Map

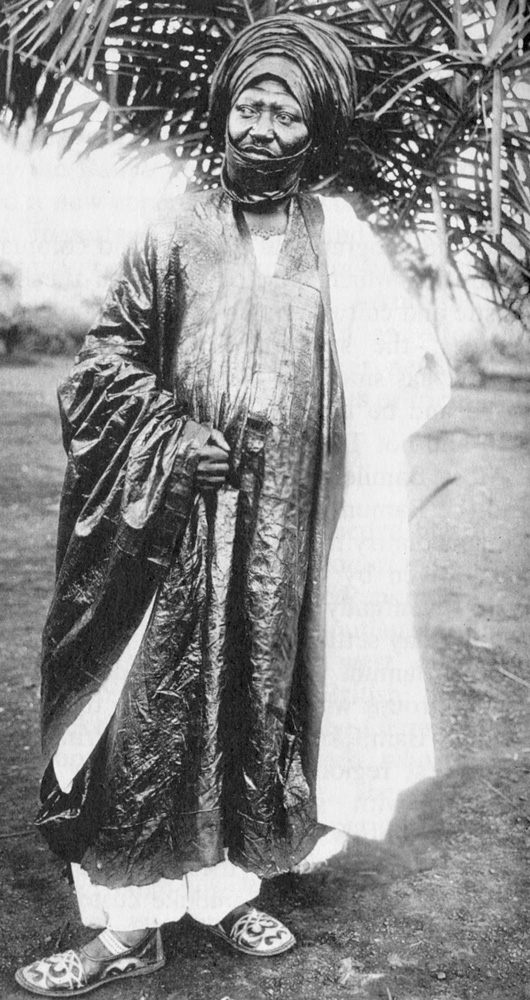

Njoya, who ruled from 1886 to his death in 1933, was the 17th Mfon in a dynasty that traced its origins back six centuries. Yet he realized that tradition alone wasn’t going to save him or his kingdom. Seeing German colonizers advance into this part of Africa, he adopted a friendly attitude and adapted from them what he could use for the benefit of his own kingdom.

For Kaiser Wilhelm II’s birthday, Njoya sent his exquisitely decorated throne as a gift to Berlin. The Kaiser was touched, called him his “royal brother”—and acknowledged the autonomy of his kingdom.

Njoya set up schools where children were educated in German and Bamum culture. They also learned to read and write using the Bamum alphabet. It was invented by King Njoya himself, who used it to write the History and Customs of the Bamum People. The seventh and final iteration of the script, whittled down to 80 characters, was commonly known as “a-ka-u-ku,” after its first four letters.

Africa, Mapped by Africans

Like with the alphabet, so too with cartography. Njoya created a map—a useful idea from the colonizers—but reconfigured it to serve the purposes of his kingdom. The result is not a European-style map, but rather, it reflects how the Bamum themselves saw their own land. Or, as put by the Twitter account Incunabula, where this map was first published online in March 2022: “A precious example of an African map made by African cartographers.”

In 1912, King Njoya ordered that a survey be taken of his kingdom. A second survey was completed in 1920. Officially, these were meant to adjudicate land disputes. Clearly, he also would have seen how useful maps were in the hands of the Germans as a tool for governance and a display of sovereignty.

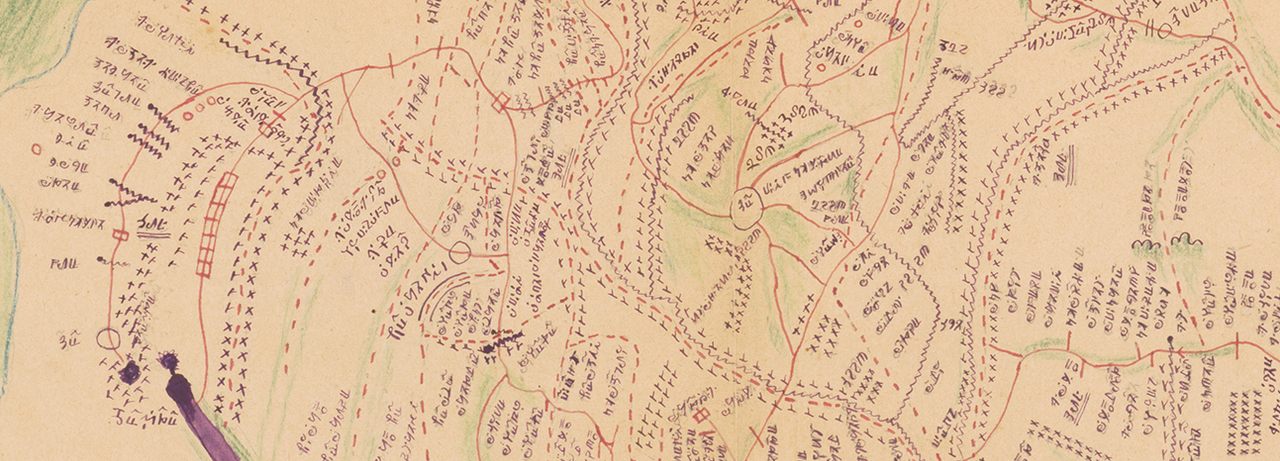

Both times, the King himself led the surveying expedition. Each consisted of teams of bush-clearers, surveyors, and servants. The surveyors’ work was checked by about 20 topographers. In all, an expedition counted about 60 people.

Purple Rivers and Green Mountains

The surveyors and topographers worked out their own system to represent what they encountered, developing Bamum standards to depict villages, markets, boundaries, and other common elements of topography. The map is oriented toward the west: two disks represent the sun rising (bottom) and setting (top). Rivers are in purple, mountains in green. The script is, of course, Njoya’s own.

The surveyors did not have access to modern surveying equipment. To assess distances, they used watches to time how long it took them to get from A to B. At each village, a local guide would accompany a survey team to assess the extent of the locality, the names of streams and mountains, and other relevant information.

One of the surviving notebooks from the first expedition shows that Njoya and his train of surveyors, servants, and topographers made 30 stops in 52 days, and managed to cover about two-thirds of the kingdom. After less than two months, the start of the rainy season made roads impassable, putting a stop to the expedition.

Dynastic Capital Since 1394

At the center of the map is the ancient walled city of Foumban, founded in 1394 by Nshare Yen, the first Mfon of the Bamum. To indicate the city’s importance as the seat of the dynasty and capital of the kingdom, it is placed more central and shown larger than it actually is.

The rivers that surround the kingdom display a remarkable symmetry—again, an exaggeration of the actual facts on the ground, and likely an attempt to create a sense of geographic unity for Bamum.

The Bamum alphabet is used to list hundreds of placenames along the kingdom’s edge. This shows that the surveyors established the kingdom’s borders on the map by walking its perimeter, akin to the old English (and New England) tradition of “beating the bounds.”

Too German-Friendly

When the French took over German Cameroon after World War I, Njoya was distrusted as having been too friendly with the Germans. He was eventually stripped of any political power and exiled to the Cameroonian capital Yaoundé, where he died two years later.

However, the Bamum dynasty survives to this day, albeit only in ceremonial form. On October 19, 2021, Nfonrifoum Mbombo Njoya Mouhamed Nabil, the 28-year-old son of the previous king-and-sultan, ascended to the throne as the 20th Mfon of the Bamum. He holds court in the Royal Palace built just over a century ago by the 17th of his line, in the style of a northern German brick mansion. Part of the palace is a museum, in which its builder figures prominently.

These days, Foumban is a popular tourist destination. One of the sights greeting its visitors is a statue of Njoya the Great—inventor, innovator, historian, mapmaker.

For more on the rich cultural climate in early-20th-century Bamum, check out this lavishly illustrated article about Ibrahim Njoya, graphic artist and cousin of the eponymous sultan.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook