The Kingfishers That Shacked Up at the Start of the Pandemic Aren’t Sick of Each Other Yet

Before the birds moved in together, they had to learn to “howdy.”

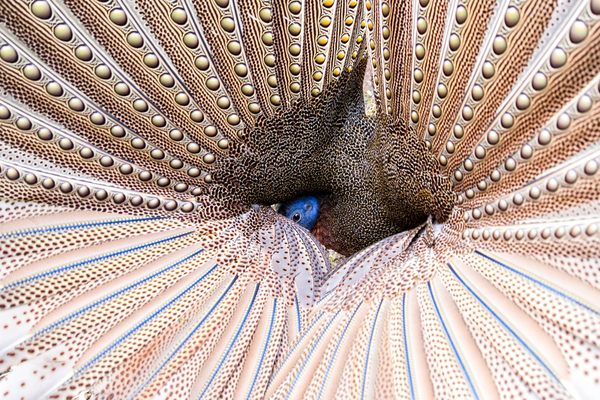

As the COVID-19 pandemic began to spread across America, fledgling couples faced a choice: batten down the hatches in their respective homes, or hunker down together? Among those who chose the latter, several months in, some are bristling, while others are still happily canoodling. At the San Antonio Zoo, things are still looking pretty rosy for a pair of Micronesian kingfishers, Todiramphus cinnamomina cinnamomina, that shacked up in March. The birds recently welcomed a hatchling—the zoo’s first of their species in several years.

Like many newly cohabitating couples, one bird moved into the other’s space. Things can get testy when one partner seems like an interloper, says Brent Nelson, the zoo’s aviculture manager. “It’s always tricky when you’re introducing one into the other’s established territory,” he adds. “If it’s neutral ground, they’re learning the lay of the land at the same time.” To emulate that, for a while at least, the birds lived side-by-side in separate holding areas, from which they could become familiar with each other without tussling over the crickets, mealworms, and anole lizards that comprise their diet. Eventually, the handlers opened the doors. The slow build to intimacy is a process known as “howdying” the birds, Nelson says. “That’s an industry term—not just a Texas thing.”

Unlike their human counterparts, the birds didn’t have to merge possessions, or hash out a shared decorative vision. Their indoor enclosure was already furnished with lush ficus, philodendrons, ferns, vines, a palm log for nesting, and enough perches to give them room to escape each other, if they felt so inclined. All the birds had to do was mutually decide not to make each other miserable.

It’s hard to predict whether any two birds will hit it off. Matchmakers are most interested in genetic diversity, because there are so few Micronesian kingfishers left—roughly 140 in captivity and none on their native island of Guam, where they were extirpated by brown tree snakes inadvertently introduced in the middle of the 20th century, Nelson says, as stowaways on military planes that stopped there to refuel. Across affiliated zoos, a single coordinator suggests which birds ought to meet, but that can only take things so far. Then it’s up to the birds. “I think of it like people going on a blind date,” Nelson says. “The geneticists could say, ‘You guys will be a good match,’ but the birds decide on their own.”

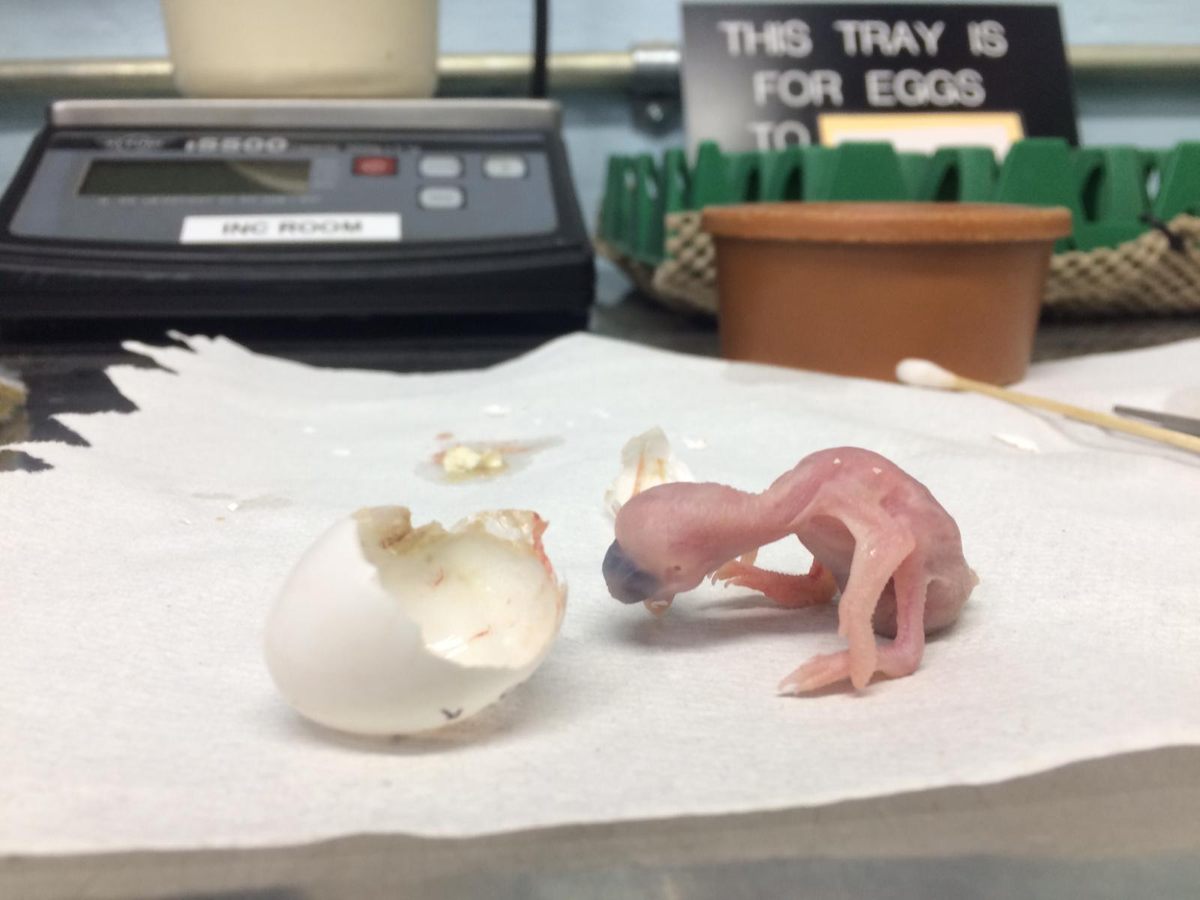

And if the birds’ verdict is that they’re not feeling it, the signals aren’t subtle. “I’ve worked with pairs before that, right away, it was oil and water,” Nelson says. When a Micronesian kingfisher doesn’t feel that spark, one might chase the other, or stick its bill up in the air so it looks like a peeved, haughty pear. The zoo had tried various pairings in recent years, Nelson adds, but nothing took: It was always “one of those situations where something was out of sync.” No such trouble with these two. “As soon as we put them together, it was like, ‘Hi, how are you?’” Nelson says. A month in they started courtship rituals, such as building a nest together, and the little one was born in June. Since the breeding season lasts through the end of summer, it’s possible another might arrive, too.

There’s no reason to think that the relationship won’t keep humming along, but then again, anything can happen. Across the animal kingdom, even partnerships that seem strong can splinter, leaving human handlers puzzled and bummed out. Take Bibi and Poldi, two Galápagos tortoises at Austria’s Reptilienzoo Happ, whose relationship spanned more than 90 years. Suddenly, one day, they were on the outs, and their keepers futilely pulled out all the stops to patch things up. For now, the birds are still going steady, but they’re still in the honeymoon phase. “They have only been together for a few months,” Nelson says. “There’s always the chance that they decide they don’t like each other anymore.” As summer drags on and the pandemic does, too, surely a few human couples can relate.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook