What Do Flamingos Do at Night?

Lessons from an avian surveillance project.

It’s a common trope in fiction: When people aren’t around to watch, other creatures of the world let down their guard. Zoo animals have secret meetings. Toys come to life. So it would make sense if, settled into bed one evening, you were suddenly seized with a white-hot nighttime question: What are the flamingos up to?

As birds go, flamingos don’t seem all that mysterious. They’re brightly colored and quite recognizable. They tend to hang around out in the open, and sometimes, when they’re in a mingling mood, they even dance.

But appearances can be deceiving. “For a large animal in the 21st century, there are still so many unknowns about them,” says Paul Rose, a flamingo expert based at the WWT Slimbridge Wetland Centre, in Gloucestershire, England. For a recent study published in Zoo Biology, Rose decided to get a new view on his study subjects, setting up a nighttime surveillance system to figure out exactly what they do when we’re away.

Rose describes himself as “a little bit of a flamingo obsessive.” He’s the co-chair of the IUCN’s Flamingo Specialist Group. His “Flamingo Diary,” which traces the lives of the Centre’s birds, covers everything from avian flu to preening habits. In his Skype profile photo, he is wearing a pink shirt.

For his dissertation, Rose focused on one particular unknown: whether flamingos form social relationships within their flocks. (It turns out they do—“They have very strongly bonded friendships, which is very nice,” he says.) Figuring this out required long days of watching individual birds interact.

But while Rose was digging through existing research on wild flamingos, he found a few papers that mentioned nocturnal behavior, too. “I thought, am I only seeing half the story with my own observations?” he says. Soon after, he continues, “I got three night vision cameras.”

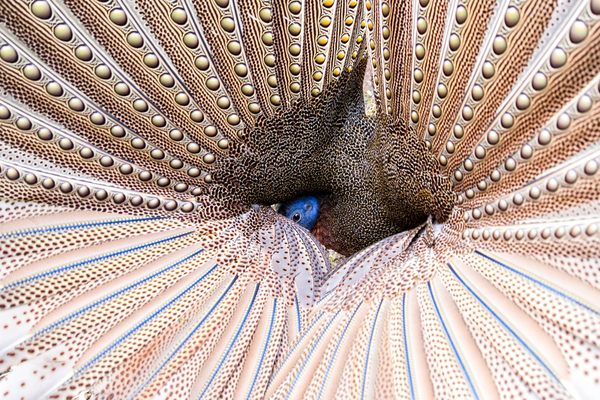

Rose and a student researcher set up the cameras around one particular Slimbridge enclosure, which houses about 270 greater flamingos. They put one on each side of the large pool, and one near a small island where the flamingos nest. They then programmed them to take photos every five minutes. After about five months of this, they were able to draw some conclusions.

For one thing, Rose says, flamingos like to snack at night. Foraging behavior, which includes searching for food in the pools or or in pellet bowls, peaked around 8 p.m. (This was particularly true on moonlit evenings, says Rose.) Parents often fed their chicks at night as well. Some birds also perform courtship displays, although most prefer to do this during the day, when their moves are more visible.

Most interestingly to Rose, they use the space differently: “They spread out much more over their pool,” he says. He is hoping these conclusions will influence the design of future enclosures, and help zoo staff to better understand the birds under their care.

In other words, when we’re not watching, flamingos mostly keep being flamingos. “Nothing too weird or wonderful to report,” Rose says. “Just what you’d expect a flamingo to do.” We can all rest easy.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook