‘Miami English’ and the Linguistic Oddness of South Florida

South Beach speech is like no other.

Florida is weird.

That much probably goes without saying; in its flora and fauna, its cultural history, its politics, its singularly bizarre criminal elements, and its natural ecosystems, there is nowhere else like it. So it should come as no surprise that, though it theoretically is part of the American South, pretty much any discussion of Southern linguistics comes with a caveat: “Well, except South Florida.”

South Floridians do not have the pin-pen merger, which makes the word “ten” sound like “tin.” They do not “front their O,” which turns a word like “boat” into “beh-oht.” They do not turn simple sounds into complex ones, like “friend” into “free-ay-ind” (this is also known as a Southern drawl). These are standards throughout the American South, and they are almost completely absent from South Florida.

So, well, what do South Floridians sound like? And how did this weirdness happen?

South Florida is not any one thing—how could it be, with a mix of Cubans, whites, Haitians, Colombians, Jews, Nicaraguans, Jamaicans, Bahamians, Barbadians, Puerto Ricans, and about a dozen others—but it’s actually always been like that.

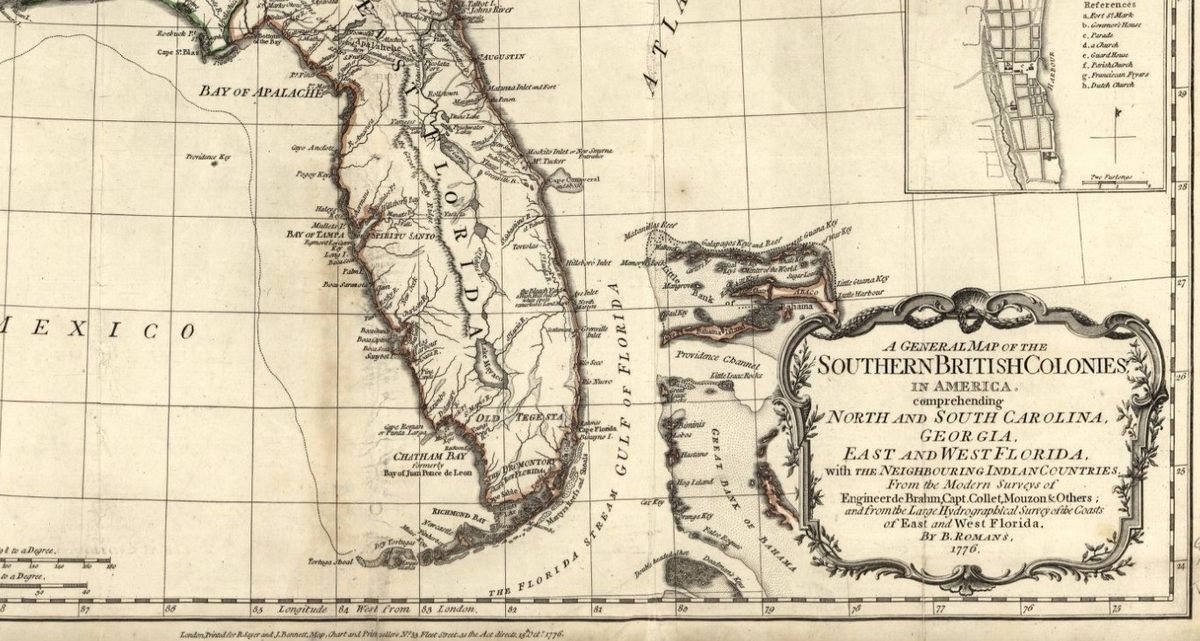

“Even in the pre-Columbian sense, South Florida is in the Caribbean, whether people want to admit that or not,” says Phillip Carter, a linguistics professor at Florida International University and one of the foremost experts on the dialect of Miami and South Florida. As far back as we can reach, the tip of the Floridian peninsula has been a site of interchange: Even the most famous of Florida indigenous groups, the Seminoles, was a heterogeneous conglomeration of tribes that didn’t even get to Florida until the early 1700s.

Links between South Florida and the islands of the Caribbean before Europeans arrived are fiercely debated, but as soon as the Spanish showed up with their nice ships and drive for exploration (and other less good things), Florida became inextricably part of the Caribbean. Pirates, treasure hunters, enslaved people. But South Florida remained extremely sparsely populated until the 20th century.

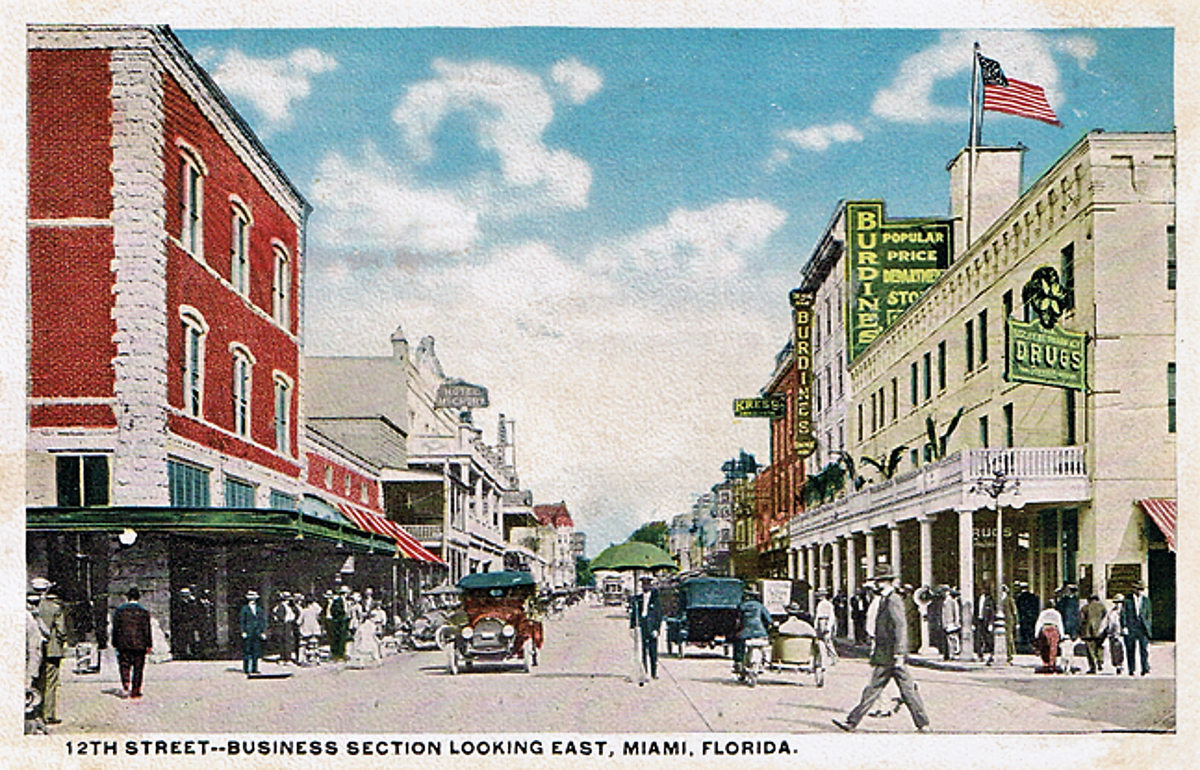

Miami is a young city; in 1900, fewer than 2,000 people lived there. South Florida, unlike North Florida and the rest of the South, never really had enough people in it to become part of the rich tapestry of its region. South Florida was, mostly, a swamp, seen as an unforgiving backwater, suited maybe for some farms but not much else. That couldn’t, and didn’t, last: By 1930, buoyed by cheap land prices, people from North Florida and Georgia began moving down to the Miami area, increasing the city’s population to more than 100,000.

By 1950, that population had more than doubled, to about 250,000, but the new Miamians weren’t, for the most part, Southerners. The promise of endless sunshine coupled with the new invention of air conditioning finally reached the North, and migrants from the Rust Belt and Northeast began coming down in droves. Italian Americans and Jews from the New York area took their place alongside Southerners.

But that all changed soon. White flight, the movement of Anglo whites from cities, began in the 1950s and 1960s. The populations of, for example, New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia, all took huge hits. But Miami’s didn’t: It kept growing. That’s all thanks to Cuba.

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 found a young Fidel Castro taking over the island nation so near to Miami. Cuba’s wealthy elite, newly targeted, fled en masse. In 1960, only 4 percent of Miami was Cuban; by 1970 it was 24 percent and by 1980 it was 36 percent. The success of Cubans in Miami, as well as Miami’s familiar climate and substantial numbers of Spanish speakers, made it a hub for people fleeing Latin America: Colombians, Nicaraguans, Hondurans, Venezuelans, Ecuadorians, and others chose Miami as their city as well.

The same thing happened with non-Spanish-speaking Caribbeans: There was already a base from the old enslavement systems, but Haitians, Jamaicans, Barbadians, Bahamians, and Trinidadians came over as well. Today Miami is 70 percent Latino, about 20 percent Black (mostly Afro-Caribbean), and only 12 percent white.

The fact that this happened so quickly has made Miami unusual, linguistically. The Miami dialect is not a second-language accent, like you’d hear from a Cuban immigrant whose first language is Spanish. It is an American English dialect like New York City English, Southern American English, or any other dialect in this country: spoken by native-born Americans who speak English either as a first language or fluently along with the language of their parents. Which doesn’t stop the accent from seeming foreign to others: Carter says that his students will sometimes find themselves in a neighboring county, only to be asked what country they’re from.

There’s a whole bunch of things that set Miami English apart from other dialects. Much of it comes from Spanish: Words or sounds that are pronounced in a certain way in Spanish will eventually show up in English. An easy one is the word “salmon,” which in Miami is pronounced with the L: “sall-mon.” That comes directly from the Spanish word for the fish, which is, well, salmón. (In Spanish, all consonants make one sound and one sound only.*)

But that letter L gets even weirder. It turns out Spanish and English have different pronunciations of the letter, which are referred to as “light L” and “dark L.” English actually has both of them: a light L is found in words starting with L, like the word “light.” A dark L is found sometimes at the ends of words, as in the word “feel.” Say that out loud. Can you hear how, in “feel,” it sounds almost like “fee-yul”? That “ull” sound as the first part of the L sound, that’s a dark L, and it’s made with a slightly different shape of your tongue in your mouth. In Miami, all L sounds are dark, so a word like “literally” sounds more like “ull-iterally.”

Vowels also show some impact from Spanish. Elsewhere in the country, English speakers have a tendency to “front” some vowels. “Front” and “back” refers to the position of your tongue in your mouth, so “ee” is a front vowel, whereas “oh” and “ooh” are back vowels. In the South and Mid-Atlantic, English speakers will move their back vowels a little to the front, so “boat” sounds like “behh-oht.” But in Spanish, that’s absolutely not done, and that carries over to Miami English. Keeping “oh” in the back isn’t unique to Miami, but it is unique to Miami within the Southern United States.

Another vowel thing: Much of the United States does this weird thing with the “ah” sound in words like “hand.” When that vowel comes before a nasal consonant—M or N—it becomes kind of nasal and more complex, turning into more like “hay-and.” Miamians, though, don’t do that, so “hand” has the exact same vowel as “cat.” Try saying it out loud. It feels strange, right? Almost British-y.

Miami English also has lots and lots of calques, which are loan phrases: essentially direct translations of Spanish phrases. In Atlanta, New York, and Seattle—actually, basically anywhere besides Miami—you get out of a car. In Miami, you get down from a car, because “down from the car” is a direct translation from the Spanish, bajar del carro. There are dozens of these:. In Miami you don’t get in line or wait in line, you make a line. You don’t get married to somebody, you get married with them. When talking about money, you don’t say “five ninety-nine” for $5.99; you say “five with ninety-nine.” If you’re not up to anything much, you might say “I’m eating shit,” the basic equivalent of “I’m not doing shit.” “Some of those English calques are based on Cuban Spanish, and my strong suspicion is that kids are learning the local variety of English unaware of the sources of the loan words,” says Carter.

The verbs “come” and “go” are also different in English and Spanish, and thus different in Miami English. “In English, the verbs ‘come’ and ‘go’ are really peculiar,” says Carter. “If you invite me to your house, I’ll say ‘I’m coming over now,’ even though what I meant to say is ‘I’m going over now.’” These words are based on “deiksis,” the relationship between the speaker and listener. Theoretically, “come” should mean heading toward the speaker or listener, and “go” should mean heading away from the speaker or listener. Come to where I am, go to this other location. But in English, it’s not that simple; we often get those totally wrong. Spanish speakers, and Miami English speakers, never get those wrong. An invitation to a birthday party in Miami might say, “Go celebrate Maria’s 10th birthday party at the zoo.” Sounds weird, but is actually correct. Neither the sender nor the receiver of the invitation is at the zoo, so it should be “go.”

One of the hardest to nail down is in the actual rhythm of speech. Spanish is syllable-timed, meaning that each syllable is spoken for the same length of time. English is not; it is stress-timed, so certain syllables, especially one-syllable words, are shorter than others. (Think about “for,” “and,” and pronouns like “he” and “she.”) Miami English isn’t exactly syllable-timed, but it’s more regular than other English dialects, which makes it sound … different, somehow. “I have heard parodies of Latinos, or Latino characters who are putting on being Latino, where you’ll find them speaking in a very fast way which gives that impression,” says Carter. It’s not that Spanish-speakers speak more quickly, just that their timing is different than English. We don’t quite know how it’s different, but speaking very quickly can sort of trigger our conception of Spanish rhythms.

Miami English is not, though, the same as other Spanish-influenced dialects of English, like Chicano English in Southern California. Some of those calques, for example, are specific to Cuba or the Caribbean and not found in Mexico. One of the most telling examples of a Southern Californian accent is turning “ing” and “ink” endings into “eeng” and “eenk,” so “thinking” becomes “theenkeeng.” These are not found at all in Miami.

Miami English isn’t only spoken by Miami Latinos, though they are the predominant group that has this dialect. Carter has found that many Anglo whites in Miami will use this dialect—but not always. Miami English coexists with Spanglish and flat-out Spanish in Miami, and speakers will often switch between those depending on who they’re speaking to. A white teenager might use the Miami English dialect with friends, and a Northeast-like accent with parents—after all, there’s a good chance the teen’s parents hail from the North.

A major part of what makes Miami English special is how quickly and thoroughly immigrant groups have come to dominate the city. In, say, New York, even the biggest immigrant groups—Italian, Irish, Puerto Rican, Dominican, Chinese—are still comparatively minor parts of the whole. But Cubans, and then other Spanish-speakers, became the dominant force in Miami so quickly that, essentially, stranger calques and pronunciations and rhythms have been free to become the norm.

Typically, a small population of immigrants surrounded by people from elsewhere would have stuff like that ironed out. “But here, basically because of the numerical profile, nobody is here to say, ‘No, it’s get married to someone, not with,’” says Carter. The norms reinforce each other. If everyone around you speaks in a certain way, it won’t be “corrected.” Miami English has been permitted to live on its own weird little linguistic island, evolving in its own utterly charming way.

*Correction: This story originally said that Spanish has no silent letters. That’s not true!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook