The Deseret Alphabet, a 38-Letter Writing System Developed by Mormons

It was intended to spell English words in a more phonetically accurate way.

Thirty-two years ago, while on a Mormon mission in Florida, amateur cryptologist Scott Reynolds was browsing a public library when he discovered a book with pages printed in a code of symbols he did not recognize. There was no key or explanation, but he copied down the peculiar characters. It would be over a decade until he discovered that the foreign-looking script was a nearly forgotten writing reform experiment called the Deseret Alphabet.

“There was very little information about the DA on the internet back then,” says Reynolds, “but enough that I finally learned what it was and where it came from. I found the first three readers [books of excerpts for language learners] on eBay and purchased them.”

Reynolds decided to create a space for people to learn. He founded a website and multiple online discussion forums.

This alternative alphabet was created more than a century ago and fell into obscurity shortly thereafter, but a modern enthusiast can download several Deseret fonts, translate between Deseret and Standard English directly on the web, or purchase a swath of transliterated paperback classics—from the The Federalist Papers and the U.S. constitution, to works of Shakespeare, P.G. Wodehouse, or Isaac Asimov. Indeed, a far greater number and variety of books are available in the Deseret Alphabet today than ever were in the time its implementation was seriously pursued. Due to its petite renaissance, fans of the popular webcomic XKCD can visit a website dedicated to transliterating each new post. And the alphabet was recently the official written language of the Republic of Molossia, a self-proclaimed micronation in Nevada.

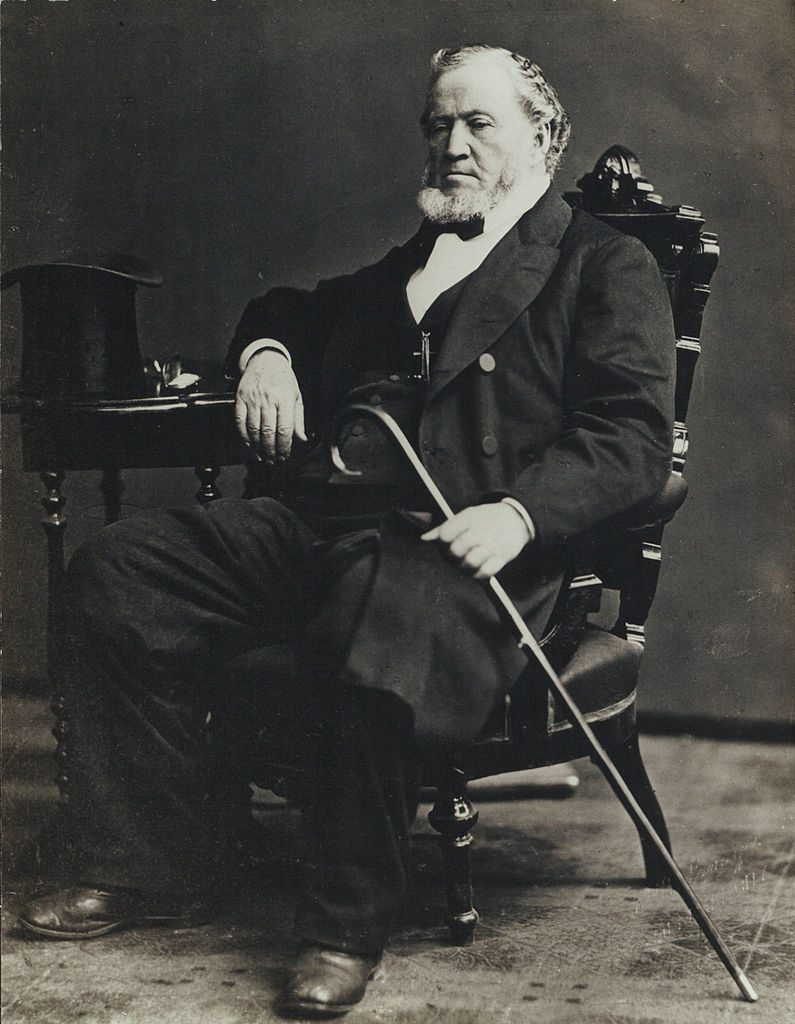

In the summer of 1847, Brigham Young, future governor of Utah, reached the Salt Lake Valley with a portion of the over 70,000 Mormon settlers who would make an arduous trek of 1,300 miles to the arid mountain deserts of the Mexican territory. An open land with few neighbors appealed to the Mormons, many of whom were multinational refugees fleeing a tumultuous relationship with the United States after the murder of Joseph Smith, the founder of their Christian sect, by an angered mob in the state of Illinois.

Young had grand plans for the Mormon settlement. He mapped a proposed state comprising what is now Utah, and Nevada, parts of seven other states, and through to a section of the Pacific Coast. He named the state Deseret—a word from The Book of Mormon meaning “honeybee,” a symbol of community and industry seen on the Utah flag to this day. Before Deseret came under U.S. jurisdiction it had its own legislature, criminal code, tax laws, militia, and a new, alternative system of writing.

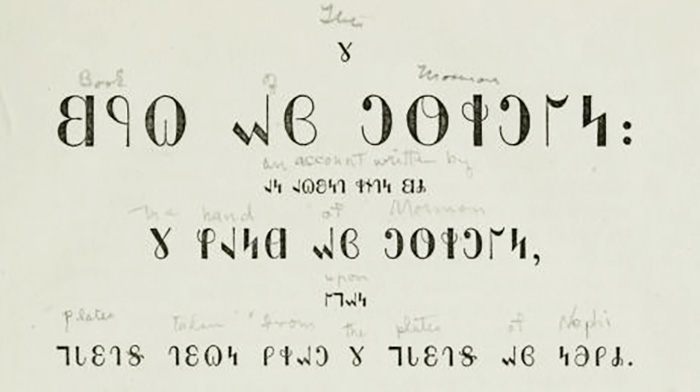

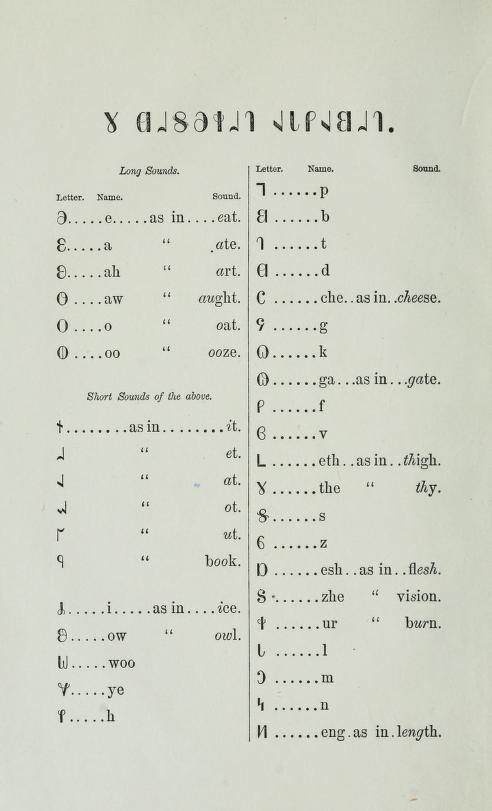

Work on the Deseret Alphabet began in the same year of the Mormon migration. The system was to simplify spelling by creating a distinct symbol for each unique sound in the English language. In January of 1854 The Deseret News printed the following:

“The Board of Regents, in company with the Governor and heads of departments, have adopted a new Alphabet, consisting of 38 characters. The Board have had frequent sittings this winter, with the sanguine hope of simplifying the English language, and especially its orthography. After many fruitless attempts to render the common alphabet of the day subservient to their purpose, they found it expedient to invent an entirely new and original set of characters.

These characters are much more simple in their structure than the usual alphabetical characters; every superfluous mark supposable, is wholly excluded from them. The written and printed hand and substantially merged in one.”

Ostensibly the alphabet was created as a beneficial reform. Young considered the “English language, in its written and printed form … one of the most prominent now in use for absurdity.” And he felt it was overly complex and confusing to a population of immigrants with diverse linguistic backgrounds. Young further believed reading and writing could be taught more effectively in schools that used the new alphabet, granting ample time to be devoted to other studies.

Critics (both today and formerly) have protested that the Deseret Alphabet was created as a means of control—keeping the Mormon population from reading outside material and keeping non-Mormon settlers and officials from easily understanding church documents. However, alternative spelling experiments were not uncommon in the English speaking world in the 19th century, and records show that Young and the creators of the alphabet were hopeful its use would spread beyond Utah.

Work on the system continued—at an eventual price near $20,000 (approximately $544,880 adjusted for inflation) to the early church government. Utah became a U.S. territory and the alphabet was taught in some schools, used for road signs, a few books, coinage, on headstones, and even in the creation of an English-Hopi dictionary (Hopi is a Native American nation located primarily in Arizona).

Public interest in the alphabet was less than hoped, however, and use never became widespread. The railroad was soon to reach Utah and with it would come a myriad of settlers and travelers unfamiliar with the alphabet. After escalating cost projections and about a decade of promotion, official attempts to enforce the use of Deseret ceased.

Of course, record of this Mormon alphabet never disappeared completely and in the new millennium, the internet has galvanized the dormant experiment.

Marco Mora-Huizar has a fascination for foreign letters and has dedicated an Instagram account to the Deseret Alphabet.

“DA has a very alien feel to it,” he says, “ When I see a design I like, I like to imagine how it would look with DA instead of Roman letters.”

For others the connection is more spiritual. Claire Wilson writes in Deseret as a hobby. She was raised in Utah as a member of the Mormon faith, but no longer practices. “Writing in Deseret feels like one of the few ways I can connect to my ancestry and my cultural history without being directly involved with the church,” she says. “And that’s important to me.”

Phonemic English-language alternatives like the Deseret Alphabet still face many of the same challenges they encountered during their height in the 19th century. The characters of the alphabet are sound-based and not classified discretely as vowels or consonants. Since the writing attempts to follow the sound exactly, confusion can result from differing pronunciation. For example, writing the word “Mormon” could be attempted differently by someone who says “mawr-men” versus someone who says “more-mon” and so on. Clarity can be further lost as pronunciation shifts over time.

Regional accents and dialects can also have a marked effect on writing. “I get tripped up all the time because of British pronunciation,” says Wilson, who now lives in London. “I spell things based on an American accent mostly because of the hard ‘R’ sounds which make it easier to read, but there are some sounds that Deseret doesn’t have letters for, and some sounds it does have a letter for, but we don’t use that sound anymore.”

The Mormons of Deseret were not the first group to attempt spelling reform—and calls for alternative spelling persist today. Advocates from Brigham Young to Mark Twain and Charles Dickens have all decried the perplexing lack of cohesion in English spelling. Renowned wordsmith George Bernard Shaw willed a portion of his life’s estate to fund the Shavian Alphabet. Tools to enact ubiquitous change are more capable ever, but so to has the global standing of English intensified. Reformers continue to plead for consistency and clarity in the face of anglophonic anarchy. Then, as now, the reply seems to be, “Go ghoti.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook