The Mesmerizing Geometry of Malaysia’s Most Complex Cakes

Bold colors and designs set kek lapis Sarawak apart.

On a 2019 episode of The Great British Baking Show, judge Paul Hollywood looks like he’s choosing his words very carefully when he speaks. “I think this is one of the hardest cake designs to make,” he says, referring to the gauntlet the judges have just thrown down for the contestants: to bake kek lapis Sarawak. “There’s nowhere to hide. We will see the problems.”

Lapis means “layers” in Bahasa Malaysia, Malaysia’s national language, and Sarawak is a state located on the northwestern coast of Borneo. The kek (cake) is aptly named. Slice off a piece and you’ll find a kaleidoscope of colorful layers, meticulously arranged in distinct geometric patterns. Making it is a long, grueling process that tests even the most seasoned of Sarawak’s bakers.

But for Sarawakian Jennifer Chen, making the layered dessert is a piece of cake. “To me, it’s easy,” she says nonchalantly. However, Chen, who picked up the recipe from a childhood friend, acknowledges that she has been perfecting her technique since the 1980s. “For a learner,” she muses, “I don’t think they can pick it up so soon. It’s very confusing.”

Kek lapis Sarawak is a relatively new dessert. It originated in the 1970s and 1980s, when the Betawi people from Indonesia introduced Sarawakians to kek lapis Betawi, or lapis legit, a localized version of the spit cakes that Dutch colonists used to enjoy. Lapis legit incorporates spices such as cinnamon, cardamom, clove, and star anise into a fluffy batter of butter, flour, and eggs, which bakers cook in multiple brown and beige layers.

Sarawak’s version of kek lapis, however, is much more colorful and complicated, with its inner layers made vibrant with food coloring and natural extracts. Bakers in Sarawak also added their own spin on the cake’s flavors, resulting in concoctions such as kek lapis Cadbury and kek lapis Oreo. Building these cakes requires a vivid imagination, an almost mathematical mind for detail, and perhaps most importantly, a steady hand.

Making one cake can take anywhere from four to eight hours, depending on the complexity of the design. It’s a process that could go wrong at any point in time: Bakers first must cook up cakes in deep pans, carefully adding even stripes of colorful batter with 10 minutes in the oven between each layer.

But making the cake is only half the battle. Kek lapis Sarawak is unique because bakers must carefully cut up the cooled cakes and reassemble them using jam or condensed milk as glue. The end result is a complex, vibrant pattern that appears when the cake is sliced.

“You need to think about the pattern,” Iban home baker Olivia anak Edward stresses, noting that each cake’s pattern and flavoring requires bakers to consider how any added ingredients would affect the design. “Let’s say you want to make kek lapis Cadbury. You need to know how to put the chocolate Cadbury in the middle,” she explains, “so that the cake doesn’t break.” Taking a deep breath, she adds, “It’s very challenging. Once you make a mistake, it won’t turn out beautifully.”

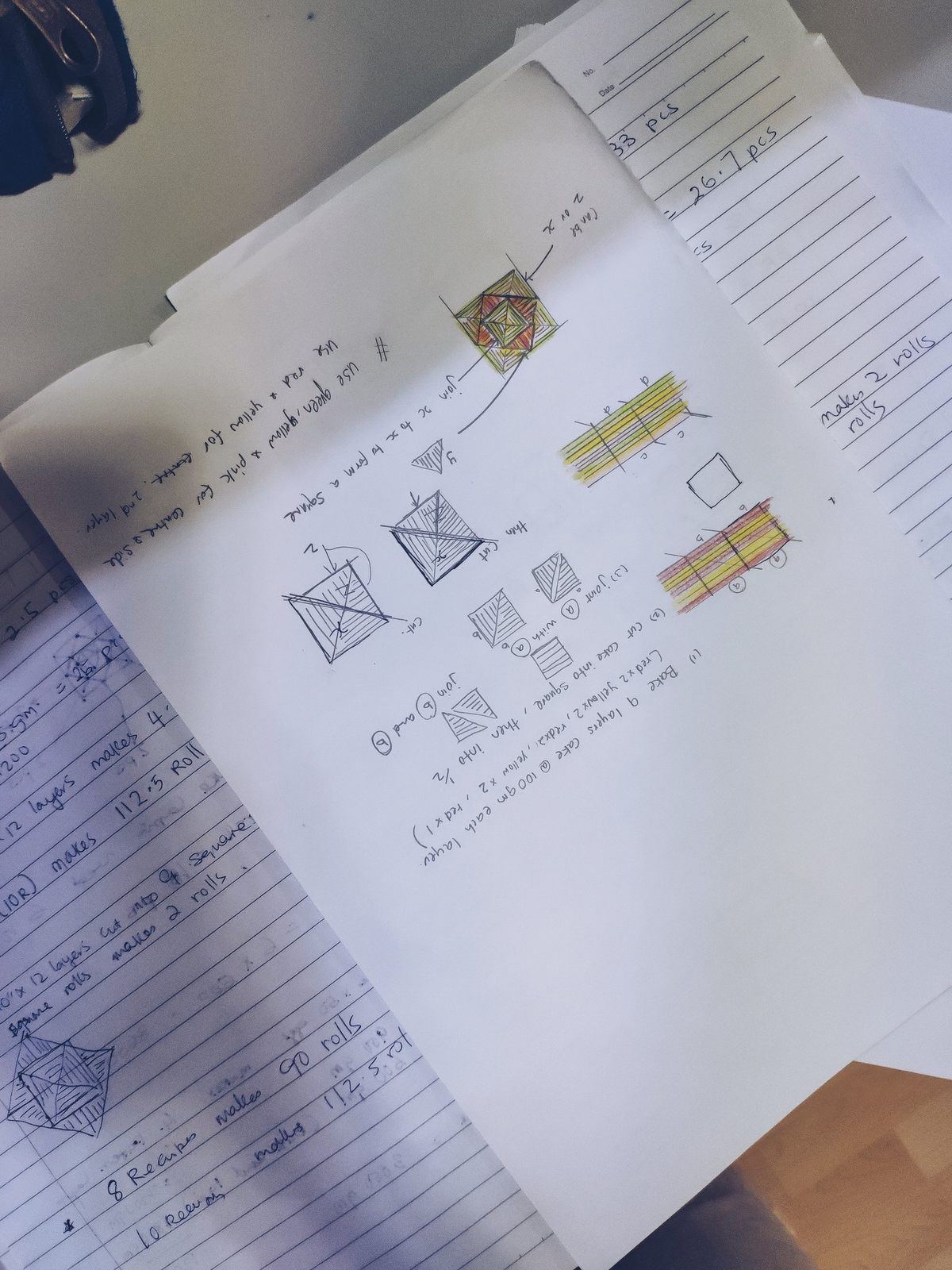

Chen, on the other hand, has developed a habit of drawing diagrams to plan her cakes. She acknowledges that things can always go awry, but even a cake sliced off-center can be salvaged. “You cut it wrongly, and then you try to redo it, make it into a new pattern,” she says.

Kek lapis Sarawak can be expensive, with prices sometimes reaching up to RM250 (approximately $59 US dollars) for a whole cake. Chen points to the high cost of butter—a crucial ingredient in ensuring the cake’s elusive silkiness—but also the intensive labor and time that goes into each one. “We have to do it ourselves and it’s very slow,” Chen says. “It’s hand-worked. We cannot do a lot.”

Kek lapis Sarawak was once only baked for holidays such as Gawai Dayak or Hari Raya, but today, it’s increasingly sold year-round for birthdays and weddings as well. In 2010, the Sarawak government designated it as a “protected geographical indicator,” decreeing that true kek lapis Sarawak can only be made within state borders.

Yet these vibrant cakes are rapidly making inroads outside Sarawak. Chen has now teamed up with her daughter to sell kek lapis Sarawak on social media, with her cakes racking up acclaim both locally and overseas. And though Edward admits that making even one cake is tiring, their show-stopping effect means that bakers are more than willing to take up the challenge. “So for us, as long as the people are happy to eat,” she says, “we are happy to do it.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook