How Invasive Moths Improved 19th-Century Astronomical Illustrations

After accidentally introducing invasive moths to North America, amateur entomologist Étienne Léopold Trouvelot turned his eyes to the skies and changed science.

One night in the late 1860s, a surprise storm slammed into Medford, Massachusetts, and the farm where lithographer and amateur entomologist Étienne Léopold Trouvelot was living. A strong gust of wind tore apart the nets where Trouvelot kept thousands of specimens of a hairy caterpillar he had imported from his native France. Several of the animals escaped into the night, forever linking Trouvelot to the destructive, highly invasive European spongy moth’s arrival in North America. During their larval phase, spongy moths can devour entire tree canopies; by the 1890s Massachusetts had a serious problem, and infestations have since spread across much of the eastern United States.

The notorious accident essentially ended Trouvelot’s aspirations as an entomologist—and led to success in a completely different area of science, one where his name is held in the highest regard. After the caterpillar escape, the French illustrator redirected his interest from insects to space and, between 1870 and 1890, created stunning depictions of the solar system. Today they are considered works of art in their own right, showcasing a unique style that is rooted in his first area of interest.

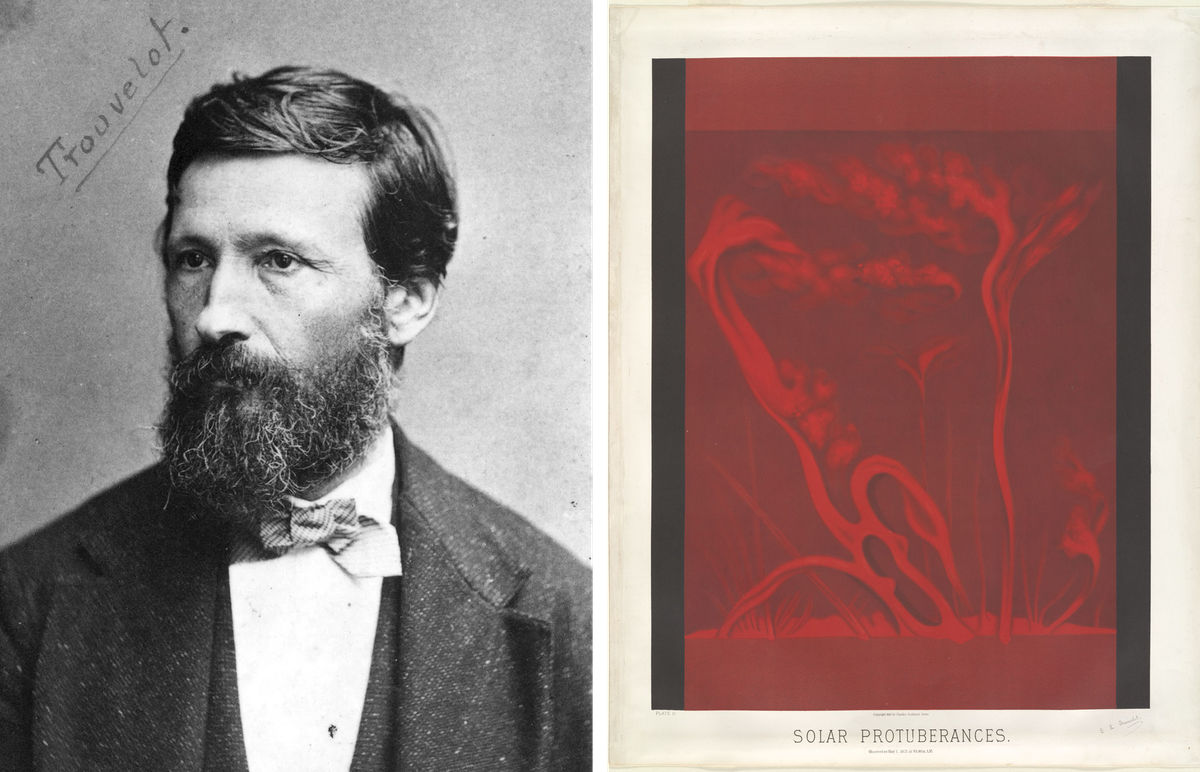

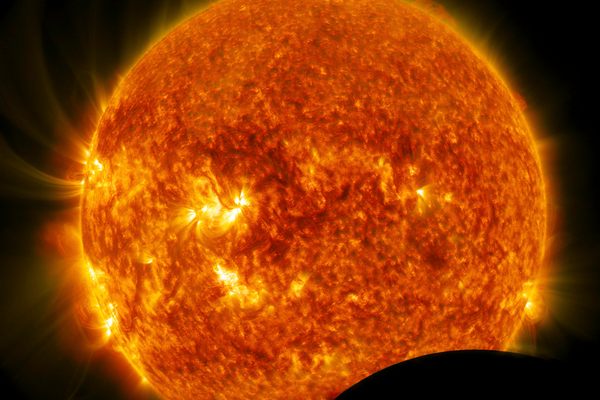

“The flames in Solar Protuberances take on an anthropomorphic quality,” says Carolyn Russo, a curator at the National Air and Space Museum, citing a drawing of solar prominences that Trouvelot made in 1873. “They create a biological sensation reminiscent of the cross-section of ventricles of the human body, or veins in animal and plant life that conjures Trouvelot’s earlier experience as an entomologist.”

Trouvelot’s drawings, adds Russo, created a “visual form of science that was engaging, beautiful, and relatable”—and played a crucial role in increasing public interest in the night sky during the late 19th century. Trouvelot might never have discovered his talent for capturing the skies had he not first accidentally introduced one of the most problematic invasive species in the U.S.

Born in 1827 in the Aisne region of northern France, Trouvelot got involved with conservative politics as a young man. He fled France in 1851 following a coup d’etat by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, also known as Napoleon III. He arrived in the United States in 1852, and settled in Medford with his wife. There, Trouvelot worked as a lithographer and pursued his passion for entomology by raising silkworms. The insects were at the core of the highly lucrative silk-making industry in France and elsewhere, but were vulnerable to disease. So Trouvelot decided to experiment with creating a silk-spinning hybrid by breeding his caterpillars with spongy moths, a native European species formerly known as gypsy moths.

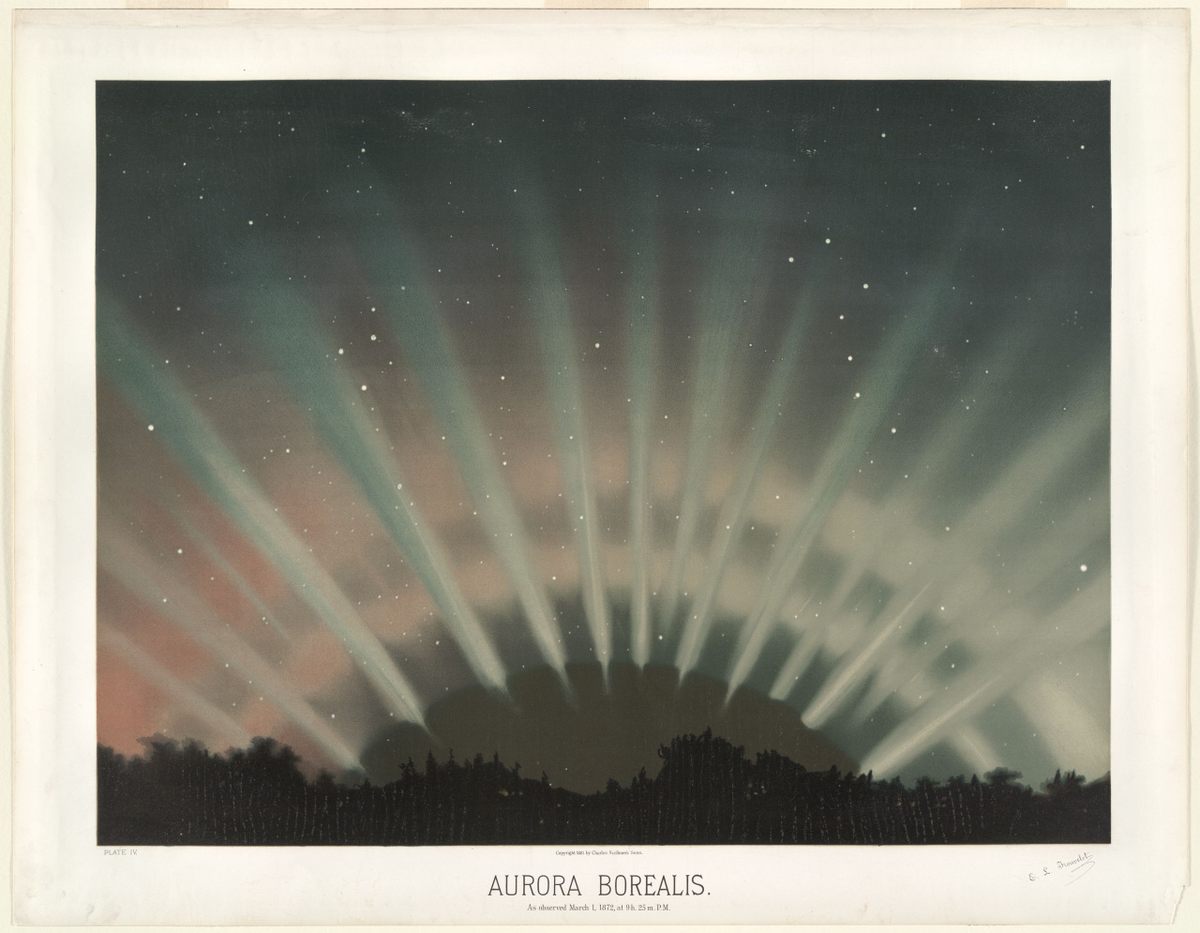

In 1870, a few months after the moth incident, Trouvelot left his farm and relocated to Cambridge, a few miles south. That October, a solar storm caused auroras to be visible at latitudes lower than usual. Inspired by this rare phenomenon, Trouvelot used his lithographic skills to make stunning illustrations of the Massachusetts night sky lit up by stripes of green and blue lights.

It was Trouvelot’s illustrations of the northern lights that led to an invitation to join the Harvard College Observatory (HCO), according to Brenda G. Corbin, a retired librarian of the U.S. Naval Observatory and author of a brief biography of the French lithographer. As Corbin wrote, observatory director Joseph Winlock felt Trouvelot combined the “qualities of an excellent observer with the skills of an accomplished artist.”

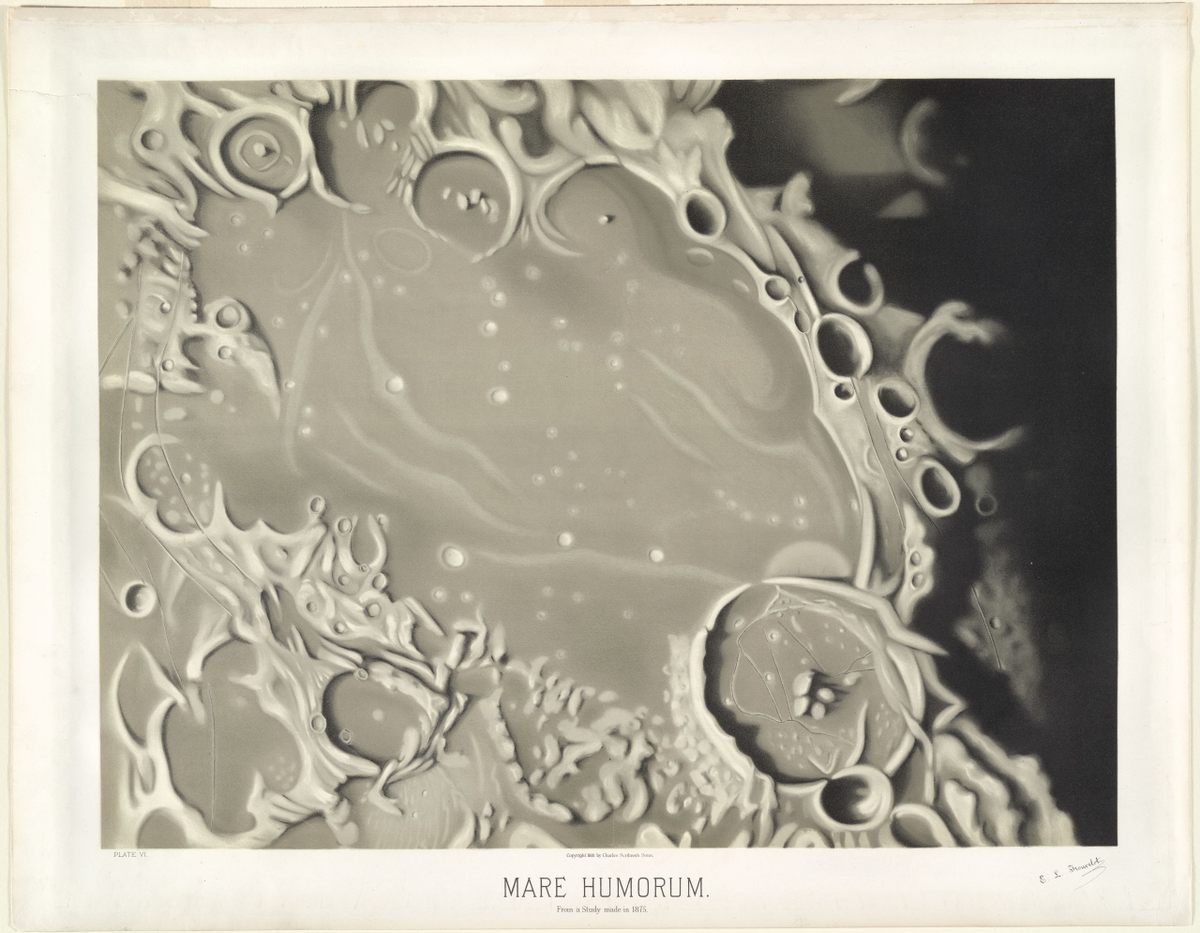

Trouvelot subsequently dedicated himself to illustrating the cosmos. During his time at Cambridge, he made hundreds of drawings of celestial objects using the HCO’s 15-inch telescope as well as a smaller, 6-inch telescope that he kept at home.

His illustrations were particularly accurate for the time—to make them, he used a classic grid technique similar to the camera interface used by some smartphones today.

“He would put a grid between his telescope lenses and then make his sketches on a paper that had a matching grid,” says Krystle Satrum, who curated an exhibition of Trouvelot’s illustrations at California’s Huntington Museum in 2018. “What really struck me is how much he strove to show a detailed and accurate image of what he saw through a telescope.”

Trouvelot was especially interested in solar phenomena and authored one of the first papers on veiled sun spots, published in the Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. For a self-taught astronomer, he left a distinctive mark in the field; he published 50 papers and an academic manual detailing his observations.

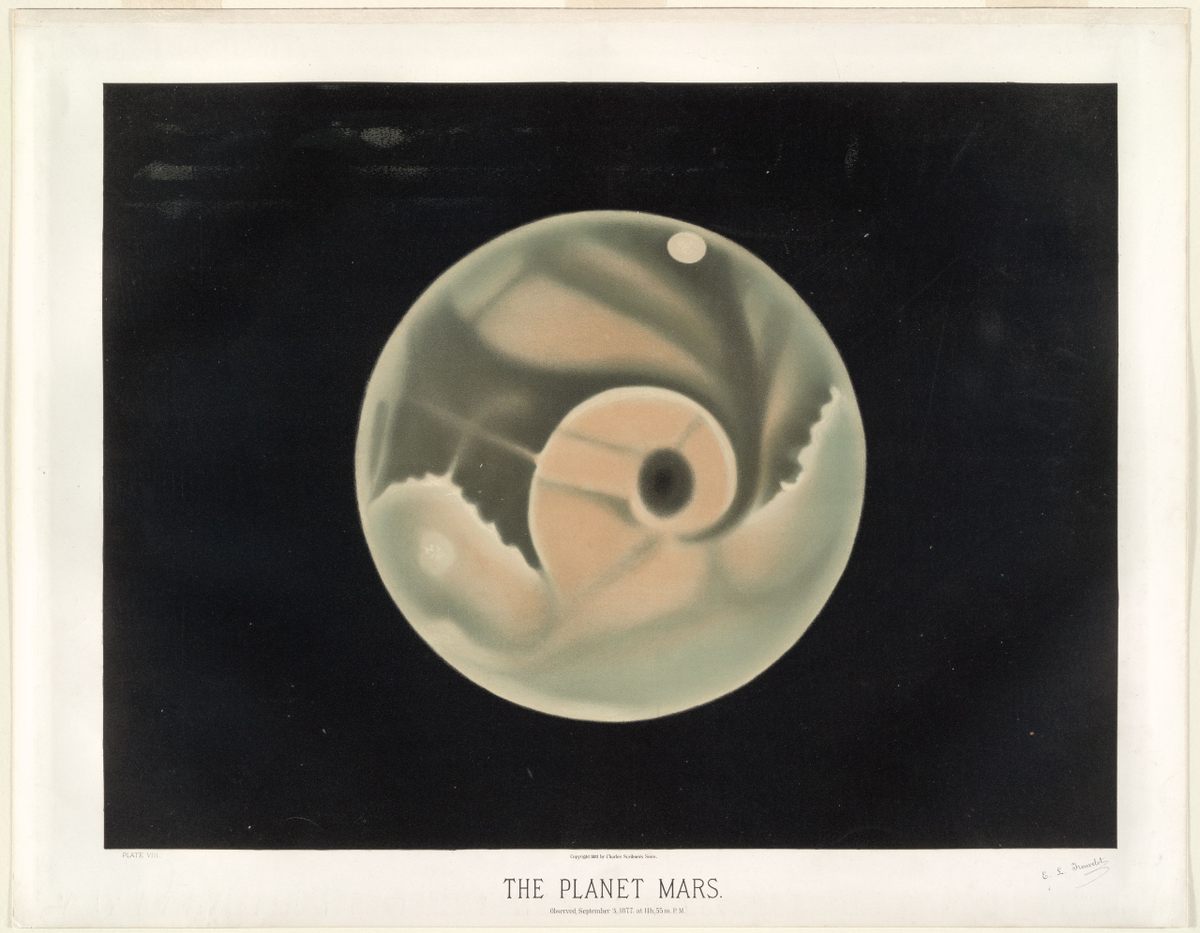

In 1875, he was invited to join the United States Naval Observatory (USNO) in Washington, D.C., to observe space using the observatory’s 26-inch telescope, the world’s largest refractor at the time. He was part of the USNO official mission to document the total solar eclipse of 1878. Trouvelot traveled to the Territory of Wyoming to capture the moment in which the moon obscured the sun. “A total eclipse of the Sun is a most beautiful and imposing phenomenon” he wrote in the solar eclipse chapter of his manual.

Trouvelot’s otherworldly illustration of the 1878 eclipse was one of 15 color lithographs of his published in an 1881 portfolio. A decade before the advent of color photography, his images were considered to be the most accurate representations of the solar system, and were used as reference tools for astronomers.

But, as photographs replaced lithographs, Trouvelot’s drawings lost their scientific value. Over time, they were instead treasured for their artistry.

“The drawings are almost too beautiful to believe that they have any scientific merit,” says Morgan Black, library director for the USNO, which has three of Trouvelot’s original pastel drawings: the Swan Nebula, Saturn, and the Great Nebula of Orion.

Nearly 150 years after their creation, Trouvelot’s drawings, some of which are now viewable as part of the digital collections of the New York Public Library (NYPL), keep drawing the interest of the public due to their nearly transcendental quality. Viewers, says Russo, feel transported into Trouvelot’s world behind the telescope. “We first see the planets and celestial phenomena up close as if for the first time,” she says, “and then, like a cosmic undertow, we are drawn into the mysteries and wonders of the universe unveiled through his art.”

In 1882, at the height of his fame, Trouvelot returned to France where he was awarded the French Academy’s Valz Prize for astronomy. There, he joined the Meudon Observatory in Paris, where he continued to observe the solar system—albeit with less impressive results thanks to the “cloudy and vaporous” Parisian skies.

Today, Trouvelot lives on in craters named after him on the Moon and Mars. Historians of astronomy remember him for his pioneering observations of veiled sun spots and those transcendent illustrations. Yet he is also linked, irrevocably, to the hairy caterpillars that munch their way through millions of acres of forest each year. His complicated legacy was perhaps best summarized by a 1989 NYPL exhibition simply titled, “Trouvelot: From Moths to Mars.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook