At This Portuguese Bakery, the Recipes Were Written by Nuns Centuries Ago

The owner of Alcôa has devoted decades to recovering lost pastries.

At first glance, Pastelaria Alcôa, a bakery in the charming little town of Alcobaça, Portugal, looks thoroughly modern. Behind a gleaming glass counter are colorful, award-winning pastries that have made the pâtisserie one of the most celebrated in the country. On warm days, customers sit outside at tables shadowed by large umbrellas and enjoy the view: a sumptuous Gothic monastery.

Alcôa’s specialities are made inside the bakery, but their roots are in buildings like the nearly 1,000-year-old religious institution across the street. In fact, the pastries are prepared precisely in the same way that nuns have produced them for centuries behind their cloistered walls. This is due to the determination of Paula Alves, the owner of Alcôa, who has devoted her life to recovering their lost recipes and techniques. “Reconstructing this gastronomic tradition feels to me like rebuilding a giant puzzle,” she says. “So much has been lost, but if you are truly committed, you will find the information you need in the most unusual places.”

It’s impossible to understand Portuguese bakery tradition without knowing about the history of the country’s convents. In the eighth century, the Arabs invaded the Iberian Peninsula, bringing with them almonds, nuts, and their prodigious culture of sweets. After crusaders retook the territory, Roman Catholic nuns built on this foundation, and when sugar was introduced to Portugal in the 1400s, the sisters started mixing it with egg yolk (often left over from using the whites when ironing noblemen’s elegant clothes), flour, and almonds, establishing the basic ingredients of convent sweets.

For the many women who joined convents not out of religious devotion but as a family obligation, the craft offered a means of personal accomplishment. “The monasteries used to host illustrious guests, which the sisters tried to impress with their most elaborate creations,” says Alves. “It was a matter of prestige for them.”

Over centuries, the sisters created a dazzling variety of earthly temptations. They showed creativity not only with the recipes, but with their names: Barrigas-de-freira (nun’s belly) is a pudding of sugar, eggs, butter, bread, and cinnamon. Papo de anjo, or angel’s chin, is prepared with egg yolk and cornstarch left in sugar syrup for 24 hours. Orelhas de abade (abbott’s ears), an ear-shaped fried sweet, was prepared for Christmas. To make beijos de freira, or nun’s kisses, nuns rolled little almond and egg-yolk balls in sugar. “In many cases the sisters created unique specialties by mixing the conventual sweets’ basic ingredients with regional products,” says Alves.

This tradition started to fade in the 1800s, after Napoleonic invasions and civil war introduced egalitarian and anti-clerical ideals. Fewer and fewer women chose monastic life, and in 1834, religious orders were abolished and the majority of convents shut down. Convent sweets endured in popular culture, and bakeries made altered versions of popular sweets such as bolo paraíso (paradise cake) or castanhas de ovos (egg chestnuts). These pastries remain incredibly popular across Portugal. But many recipes almost completely vanished, and Alves believed industrialization undermined the conventual-sweet tradition, as bakeries sacrificed quality and replaced hours of meditative rolling and folding with flipping switches on KitchenAids.

“Nuns had a lot of free time, and they employed it in perfecting their convent sweets,” she says. “Time is a key element. It is not possible to accelerate the process without sacrificing the flavor.”

This was the state of convent sweets in 1983, when Alves bought Alcôa along with her husband, who had been an employee at the bakery. She was only 20 years old, but already resolute that she would not employ the same shortcuts. She wanted to recover the nuns’ lost pastries and make convent sweets precisely the same way the sisters had.

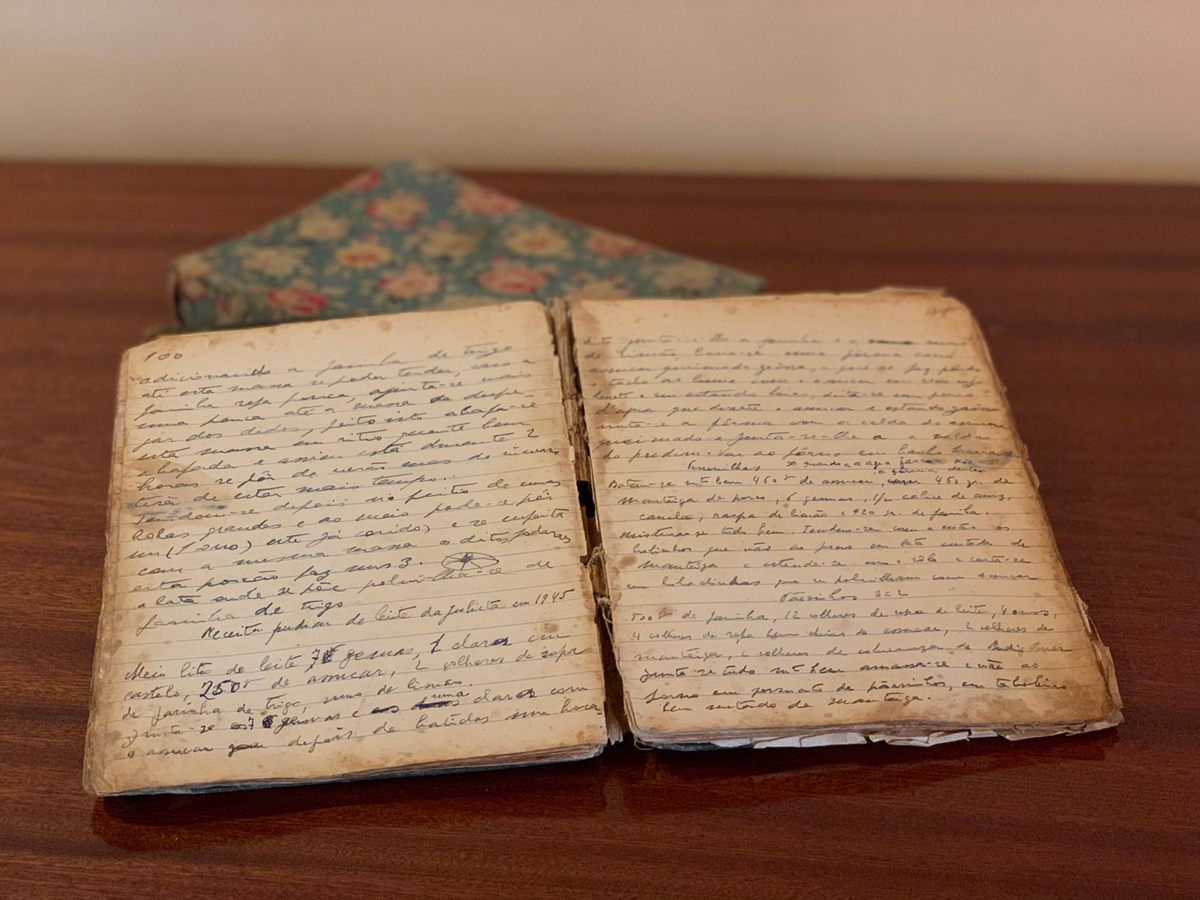

Alves’s passion for the project dated back to a gift she received when she was seven years old: a dusty, yellow-paged notebook, consumed by time and handwritten in several elegant calligraphies. It was an age-old recipe book that had been in her family for generations. While growing up, she practiced her precious notebook recipes and learned valuable tricks in the kitchen of the convent school where she studied for five years.

But Alves faced a formidable obstacle in her quest: the sisters’ penchant for secrecy. Since the monasteries’ prestige was linked to their exquisite sweets, each convent hid their recipes, and after 1834, the remaining nuns, who baked to support themselves, were reluctant to share their knowledge. “They left very few clues behind,” sighs Alves. “And to retrieve them was not an easy task.”

Her first idea was to consult the minutes of the Alcobaça monasteries. “The 18th-century novelist William Beckford mentioned that Santa Maria de Cós Monastery was the place where he found the most diversified sweet production in all of his extensive travels,” says Alves. “Since it was such a prestigious convent, girls came from Portugal’s richest families and brought the most sophisticated recipes.”

In historical archives and local libraries, Alves spent hours reading original versions of these and other ancient documents, which have miraculously survived the devastating 1755 Lisbon earthquake and Napoleonic invasions. She got used to deciphering old handwriting to learn about the processes and materials used for sweet production, and to convert old measurements to determine the exact amount of sugar or flour required in each recipe. She read as passionately as one reads romance novels, paying attention to small details such as side annotations or personal comments. All the while, her own kitchen served as her experimental laboratory. It’s where she reproduced dozens of different versions of cornucópias, little cones made with a crispy dough filled with egg-yolk cream, until she found the perfect consistency of the dough and a sublime taste for the cream. Today, cornucópias are Alcôa’s best-selling item.

She was delighting her family and friends, and starting to sell her new discoveries in Alcôa, but she wasn’t satisfied. In time, she realized the missing ingredient was the human touch. Even if the monastery had closed in 1834, the laywomen of Alcobaça had worked for centuries in the monastery’s kitchen and passed down their experience, as well as the intangible wisdom not found in books, within their families. So Alves knocked on every door of Alcobaça in search of these descendants and interviewed them. One woman was so moved that she gave Alves her personal recipe book and showed her how to bake her favorites.

Her interest eventually grew larger than the boundaries of her own region. She traveled the country, visiting surviving monasteries and driving hundreds of miles every time she heard about someone who kept an ancestral gastronomic tradition. “I was particularly touched by this old lady in the Alentejo region, who had baked the best nogado [a triangular-shaped dry fruit sweet] that I ever ate,” says Alves. She was almost 90 years old, couldn’t read or write, and knew the recipe by heart. “But she refused to give it to anyone. Suddenly, just two months before she died, she shared her secret with me: She showed me the way she cut the dry-fruit dough and rolled it in the honey cream. It was such a small detail, but it made a complete difference.”

Alves’s efforts were enthusiastically received by the public. Local and national newspapers interviewed her and published exceptional reviews of her recovered pastries. Business has expanded, but Alves continues to dedicate time to her investigation.

Her research has produced an impressive library on the subject. She has collected, for instance, 17 different recipes of toucinho-do-céu, or bacon from heaven, a delightful almond cake produced in several monasteries with regional variations, as well as custom utensils used by nuns in monastery kitchens. One of them—an aluminum funnel used to create fios de ovos, or egg threads, also known as angel hair—divides egg yolks into thin threads that can be dropped into boiling sugar and stirred. This is the key ingredient for divina gula, or divine gluttony, one of the bakery’s bestsellers.

Entering the Alcôa kitchen feels like stepping back in time. Inspired by the nuns, the bakers use only copper pots, stone mortars, and other antique instruments, which Alves believes improve the taste. There are no machines or freezers, either—they break eggs by hand, one-by-one, right in the moment, just like sisters did for centuries. Alves likes to call Alcôa a “handicraft workshop.” Still, they make some accommodations to modernity and current tastes: Deviating from the more-austere original recipe for queijinho-do-céu, or heaven’s little cheese, for instance, they cover it with icing and caramel tears.

Every year, Pastelaria Alcôa introduces a new convent sweet based on Alves’s research. “It is very arduous work that consumes most of my time even today,” she says. In 21 years, the bakery’s creations have won 14 first prizes in the most renowned national convent-sweets competitions. But just like the sisters who inspire her, her personal and professional high point was baking for a distinguished guest: Pope Francis, whom she met when he visited Portugal in 2017. “It was a dream come true,” she says. “I just couldn’t hold back my tears.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook