The Mystery of Italy’s Saltless Bread

Trade wars, papal rebellion, or salty hams. Why does central Italian bread have no salt?

Ask anyone from central Italy what is distinctive about their local bread and you’re almost certain to hear the same thing: “È senza sale.” Unlike the bread baked elsewhere in the country—and the world, for that matter—“It is without salt.”

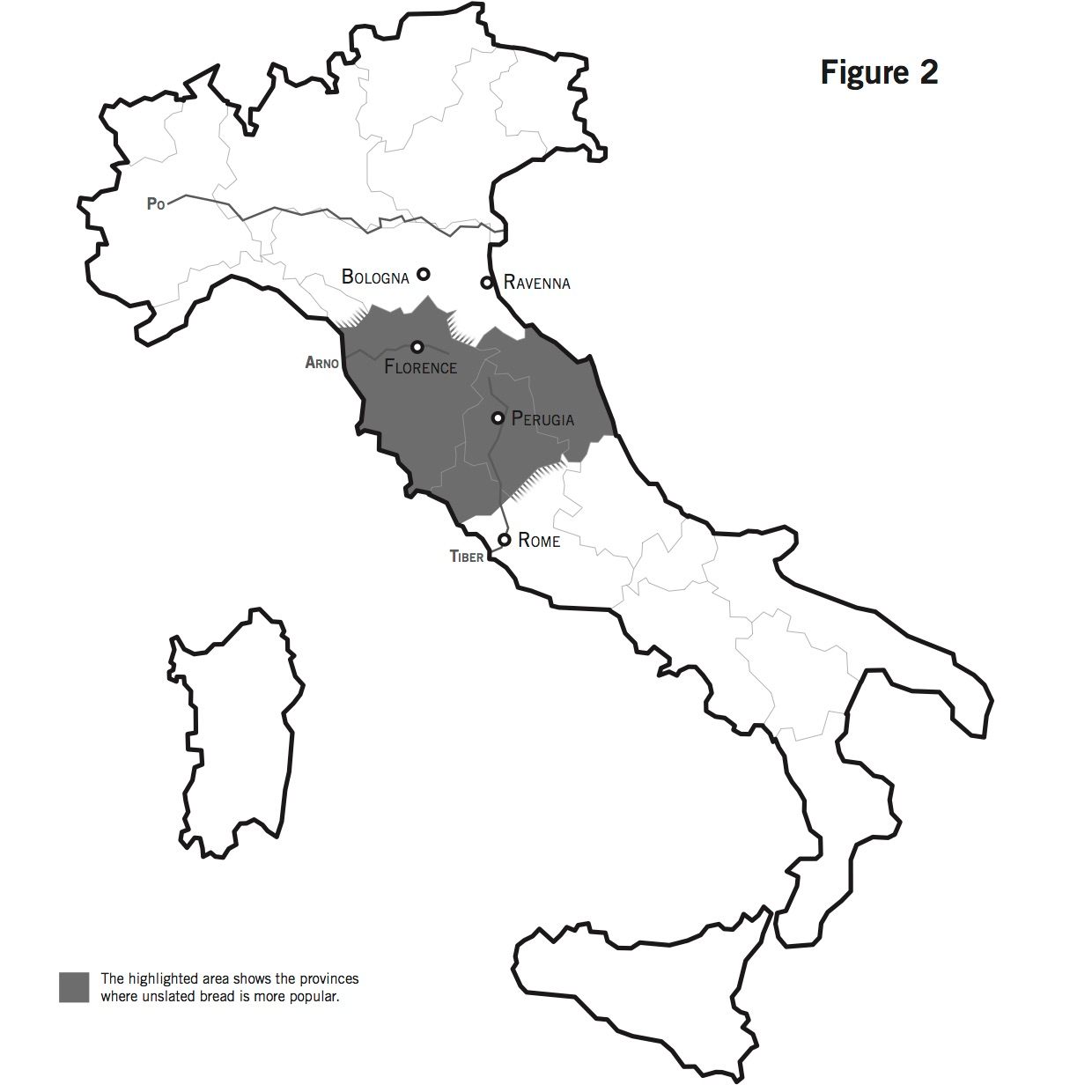

But if you go on to ask someone from Tuscany, Umbria, or Marche (three central Italian regions where most towns bake unsalted bread) why that is, you’re not going to hear a universal, accepted answer. You might hear stories about trade wars or tax-avoidance strategies between the ninth and 15th centuries, when most of the peninsula was governed by autonomous city-states. But none of these explanations tells the whole story.

In the edited 2016 volume Gastronomy and Culture, an essay titled “The Evolving Role of Bread in the Tuscan Gastronomic Culture” states that Florentine bread is made without salt because of a trade dispute with Pisa in 1100. Other sources cite a steep salt tax that pushed Florentines to do without. The most epic of these bread-splaining histories is probably that of Perugia’s 1540 Salt War. “It’s a very good story, I believed it for years when living in Italy,” says Zachary Nowak, a doctoral candidate in American Studies at Harvard University who, with Ivana De Biase, from the University of Perugia, coauthored an article on the subject in a recent issue of the Journal of Italian Studies.

Nowak spent years in Perugia working with the Umbra Institute, which offers study abroad programs for American students in Italy. He had heard the Salt War story in bakeries and restaurants around town. “Everyone in Perugia knows the story. The first time you eat pane sciapo—saltless bread—people tell you the story.”

“We make pane sciapo because Perugia went to war against the Pope in 1540,” says Silvia Duranti, owner of local bakery chain Santino. “He imposed an heavy tax on salt and people refused to pay it.” Duranti’s explanation fits with the Perugian’s fiercely rebellious and anticlerical reputation. It is also rooted in actual history, but as to whether the Salt War is the root of pane sciapo … well, that isn’t crystal clear.

In 1540, Alessandro Farnese—Pope Paul III—controlled much of the region, and though Perugia was not exempt from from his rule, it enjoyed a fair degree of autonomy. Its ruler, Braccio I Baglioni, served as chief of the city’s papal army and was therefore able to establish de facto political control. One of the results of this, Nowak and De Biase explain, was that the city was free from one of the most important papal levies at the time: the tax on salt.

“Salt was a very expensive product,” says Nowak. “It was like gasoline is now, a fundamental item for everyday life. You needed it to preserve meat and to make seasonings.” The Pope had a monopoly on all salt sold in the papal states. “Taxes on salt were a huge part of income, they probably added up to something like 50 percent of papal revenues.”

Peruginis had made an agreement with Pope Eugene IV in 1431 that granted them the right to buy salt from other suppliers. “Before Pope Paul III, Peruginis could buy salt from across the border in Tuscany, from the Senese. They could buy better salt for cheaper,” says Nowak. But in 1540 Paul III changed his mind and called off the agreement. The price of salt nearly doubled. Peruginis, already contending with a bad harvest, did not take it well. They refuted his assertion that he needed the money to fight the Turks in the east and the Germans in the north, Nowak explains, and assumed that all the money would go to the lavish court in Rome.

They refused to comply, and the Pope cut them off from church services. In response, the city declared its independence and prepared for war. “On April 18, 1540, the Peruginis attached a crucifix to the side of the cathedral [still known as the Salt Jesus] and symbolically entrusted the keys of the city to it,” Nowak and De Biase write. Many of the town’s most important families showed up to to kneel in front of the crucifix to symbolize their vow to defend the town’s liberty.

Paul III sent in his troops, who crushed the city’s armed resistance. By June 6, Pier Luigi Farnese, the Pope’s son and lieutenant, seized control of the town. And under papal rule it would remain until the unification of Italy in 1860.

So, for proud Peruginis, saltless bread is a continuation of a fierce act of rebellion. “We stopped putting salt in bread as we always had a thing against the Pope,” the baker Duranti says.

But it’s not all so simple. “I believed it for years when I was in Perugia but then I went to Florence and the bread was the same. I thought: ‘Florence had nothing to do with Papal States,’” Nowak says. “They were part of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and not under papal rule.”

He spent months looking for evidence that could help solve the mystery. First, he determined the “geography of unsalted bread” by calling the provincial authorities of 25 central Italian provinces and a single southern one to ask which kind of bread is most common in local bakeries.

The territory mapped, he then began to look at potential environmental factors. One source he found explained that central Italian regions had little access to salt due to their distance from the sea. But that doesn’t explain why the interior of Sicily and central northern Italy both bake salted bread, or account for the presence of canal and river systems for transporting salt. “If distance from the sea was a factor, then you would have pane sciapo only in the middle of the peninsula and in the middle of Sicily, rather than in this oddly shaped area.”

Nowak also sorted through the ricordi (memories) kept by local “gentlemen historians” that belonged to some of Perugia’s most prominent families. He found no mention of removing salt from bread recipes as a result of the 1540 war.

“Plus, if people were used to putting salt in bread they would logically restore to it after the revolt was crushed,” he says. “But they didn’t. So it must have deeper roots.”

Indeed, a reference to bread and salt can be found in Dante’s Divine Comedy, completed in 1320, more than two centuries before the Salt War. In the Canto XVII* of Paradiso, Dante meets fellow Florentine Cacciaguida, who warns the poet about the pain of his imminent exile:

You shall leave everything you love most dearly:

this is the arrow that the bow of exile

shoots first. You are to know the bitter taste

of others’ bread, how salt it is, and know

how hard a path it is for one who goes

descending and ascending others’ stairs.

Of course many posit that the reference to salted bread is a metaphor—to say something is “salty” means it is expensive or requires a lot of effort in contemporary Italian—but why specify the saltiness of bread if all bread was salted? “Every commentator said it was metaphorical,” Nowak says. “But I think that for a Florentine to understand that metaphor there needs to be a real world connection. It makes more sense to me that it’s a hint to unsalted bread at the time and a metaphor, rather than just a metaphor.”

Finally, Nowak looked at the pre–Salt War records kept by Perugia’s most important hospital, the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Misericordia. “Hospitals kept amazing records back then, they kept track of every single lira that was spent,” the historian says. “I checked inventories and found detailed lists mentioning pots, beans, coal, wood … but never salt. They even had their own bakery, but never bought salt.” Absence of proof is not proof of absence, but it suggests that Perugini bread lacked salt well before the Salt War.

My 90-year-old grandmother, who spent much of her childhood in Poppi, a small town 20 miles from Arezzo in eastern Tuscany, had a much more practical take on the tradition: “Tuscans make saltless bread as everything else is very salty. Cured ham is so salty that we usually eat it with saltless bread and figs that counterbalance the taste. Plus, saltless bread lasts longer.”

Nowak gave this hypothesis a thought and dismissed it. “If that was the reason, we would find saltless bread in other regions where hams and cheese are very salty, like Apulia or Calabria [in southern Italy].”

It’s possible that it’s all of these reasons and none of them. “My theory is that it goes way back, before the Salt War and even before Dante,” Nowak says. “Back in the 800s or even earlier, but the weakness of my investigation is that I have not found an alternative hypothesis for how unsalted bread evolved.” For now, the case of the unsalted bread will remain unsolved as well.

* Correction: This story was updated to correct the number of the Canto from Paradiso.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook