Herds of Mysterious ‘Glacier Mice’ Baffle Scientists

These moss balls move in unison, and researchers are okay with not knowing why.

In 1950, Icelandic researcher Jón Eyþórsson came across a gathering of fuzzy green puff balls, the size of small gerbils, scattered across Hrútárjökull Glacier in the southeast of the country. Curiously, the mossy balls weren’t attached to the ground, and many were green on all sides, indicating they must slowly turn so that the entire exterior sees the sun at some point, theorized Eyþórsson. That fall, he wrote a letter to the editor of the Journal of Glaciology. “I call these mossy balls Jökla-mýs, literally ‘glacier mice,’” he wrote, “and you will have noted, Sir, that rolling stones can gather moss.”

The term “glacier mice” has gone on to befuddle folks ever since. “I don’t like the term ‘glacier mice,’” says high mountain ecologist Scott Hotaling of Utah State University. “I saw it and I was like, ‘Oh, these are actual mammals living on glaciers.’ And that’s not even remotely what they are.” Hotaling prefers “glacier moss balls.” “They’re still surprisingly cute and herd around the glacier together—they’re awfully neat in that way.”

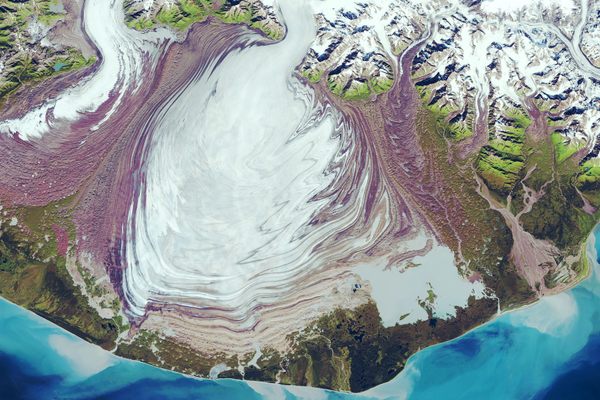

Whatever you call them, they’re cute and it turns out, quite confusing for scientists. Moss balls like these form around an irritant such as a small rock or accumulation of dust, similar to how a pearl forms around a grain of sand in an oyster. Their pillowy bodies are moss, through and through. While they’re considered rare—they require a perfect combination of glacier, moss spores, and substrate—they’ve been found, on occasion, all over the world, from the Himalayas to South America to Alaska. “They’re global but rare everywhere,” says glaciologist Tim Bartholomaus at University of Idaho. Despite being much loved by glaciologists and those lucky enough to spot them, there’s a lot we still don’t know about these mossy mysteries.

Previously unaware of the phenomenon, Bartholomaus came across a colony of the moss balls while setting up research equipment on Root Glacier in Alaska in 2006. “I was floored, and perplexed,” he says. In 2009, he and another researcher tagged 30 of them—ranging from hamster- to rat-size—with wire and glass beads, like friendship bracelets. For 54 days they tracked the balls as they moved slowly across the ice. They continued to check on the moss balls throughout the year, and returned in 2010 and 2012 to see what the little herd was up to. Hotaling, while he didn’t lay eyes on these specific fluff balls, helped with the data.

In 2020 in the journal Polar Biology, they reported that the balls slowly rolled in unison, up to a couple inches a day, and could live for at least six years. The balls moved at about the same speed, in the same direction, and changed direction in coordinated fashion. The team theorized, like the few moss ball enthusiasts before them, that the balls move because they shield the ice beneath them from melting, causing them to eventually roll off their icy pedestals. While this has been observed, that alone wouldn’t lead the balls in any single direction.

The factors that orchestrate their coordinated movements is still a mystery. Researchers tried explaining this phenomenon with incline, wind, sunlight—but nothing quite lined up. “We don’t really know why they moved the way they do,” says Hotaling. “My guess is there’s some combination of things happening, like wind, solar radiation, and micro-topography on the glacier—like melt channels and little ridges that aren’t being captured in our study. It was quite the surprise to not be able to explain it with what we thought were kind of the only options.”

Today, the moss balls of Root Glacier are still around, says Bartholomaus, though he hasn’t done an exhaustive search to see if any still sport their bracelets. At the moment, no one is on the case to try to solve this adorable green mystery. “Nobody’s lives depend on this,” says Bartholomaus, “so it doesn’t really go beyond a kind of curiosity.” Travel to glaciers is time-consuming and expensive, both researchers point out, and while moss balls are fascinating, some things are okay with a little mystery. “Scientists are trained to explain things, often with tons of caveats,” says Hotaling. “We rarely just say, ‘I don’t know.’” While Hotaling would still love to research more on moss balls, glacial researchers have more pressing issues.

Climate change and melting glaciers will surely have an impact on the moss balls—whether that means more or less, scientists can’t say for certain. Hotaling is more concerned with this bigger picture. “It’s not really just about glacier moss balls, says Hotaling, “it’s about this kind of entire system that’s going away and that we know very little about.”

Like the deep ocean, high-mountain ecosystems are full of mysteries, and each new discovery in glacial areas around the world can be as alarming as it is exciting. “No one could really imagine that glacier moss balls are a thing. The way they work and the way they move in concert, like a little herd on the glacier, that’s just not something that I would have just guessed was out there,” Hotaling says. “For me, it highlights the general issue of climate change and high-mountain and high-latitude ice, and that these places are extremely underexplored, and they’re very understudied. It makes me wonder what else is out there, and what else is being lost?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook