The German Church Smashed to Smithereens to Make Room for Coal

The town sat atop a trove of rock that was irresistible to fuel companies.

When buildings are knocked down, people often don’t let them go without a fight. This week, we’re remembering some particularly contentious demolitions. Previously: a Hollywood funeral for a restaurant named for a hat.

The church fell to pieces on a Monday in January 2018. Little light cracked across the gray morning, and environmental activists were already stationed along the metal fence ringing the two-spired structure in the German town of Immerath, a small village southwest of Düsseldorf.

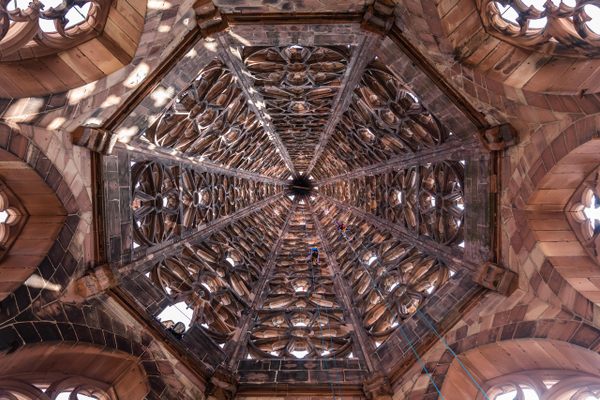

St. Lambertus went up in the 19th century, and was known among locals as Immerather Dom. That morning, people had laid roses and wreaths on the ground in front of the fence, and strung tulips to it, next to banners that read, in German, “Thank you for always being there for us.” A guitar-strumming crooner and his keyboardist set up nearby. Bundled in caps and scarves, they played a love song they’d written for the building. Some Greenpeace activists had chained their bodies to rusting construction equipment, kneeling on the pavement as hard-hatted workers milled behind them. Others had bested the fence somehow, and appeared to rappel from the church’s busted windows to hang a banner protesting the reason for its demise.

The protestors delayed the wrecking crew by a few hours, but were well aware that their stunts wouldn’t halt the building’s death. “Today is a day of mourning and disappointment,” one man told a local German-language news station. Perhaps it was a day of anger, too, he added—the church had become the latest, and most visible, symbol of an entire town being razed to accommodate the coal industry.

The community of Immerath once had around 1,200 inhabitants, who lived above a type of buried treasure. By digging, the energy giant RWE was sure that they could extract lignite—a soft, brown coal that comprises a key part of Germany’s energy landscape. The lowest grade of coal, lignite is relatively cheap and mined in fairly shallow pits, the Washington Post reported. These may not be deep, but they’re sprawling: Garzweiler, the mine that would be expanded and displace Immerath, was expected to take up a field of roughly 44 square miles, with 12 of those being actively worked, Reuters reported. (In total, the project would level 20 villages, according to Reuters.)

Germany is one of the world’s major lignite producers, and—like other types of coal—brown coal burns dirty. In 2016, the last year for which data is available through the International Energy Agency, Germany’s CO2 emissions from burning coal were among the highest in Europe—roughly 331 tons (301 metric tonnes). (In the same year, the United States’ emissions from coal were more than four-and-half times that, according to the IEA.)

A spokesperson for the energy company RWE told the German news cameras that he empathized with the people who were losing a pillar of their community (church services had stopped a few years prior), but he said that lignite helped meet much of Germany’s electrical demands in the previous year, and that renewable sources couldn’t yet fuel the country on their own.

News of the buried trove wasn’t especially welcome among the residents of Immerath, which had slowly become “a ghost town,” Huff Post reported. Over a few years, homes, graves, and landmarks were razed or moved a few miles away, to a new village—Immerath-Neu—built by the energy company. The two villages were kindred in name only, the Post reported: “The new one is tidy and austere, with suburban-style housing and a central plaza anchored by a squat, beige, nearly windowless chapel.” There was a miniature replica of Immerather Dom, too.

Back in old Immerath, the old building came down. As the equipment gripped and yanked one bell tower, then the other, the demolition looked effortless, as though the structure had been no sturdier than a sandcastle.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook