Inside the Company Printing America’s Community Cookbooks

Churches, scout troops, and clown collectives all depend on Morris Press.

Kearney, Nebraska, is best known as a stopping point for migrating sandhill cranes. Other than seasonal birdwatchers, the town doesn’t get many other tourists. But some people make the pilgrimage to Kearney for something else entirely. Past the endless cornfields, a building beckons visitors to stop with a red-and-white sign, offering a free cookbook to all comers. A step inside will whisk you away from the surrounding farmland and into a magical cookbook collection, filled with creative tomes written by everyone from church ladies to bikers. Morris Press is the United States’ largest community cookbook publisher, and, at their Kearney headquarters, the diversity of their catalog is on full, delightful display.

First, a quick introduction to the community cookbook. According to Don Lindgren—an antiquarian bookseller currently editing a multi-volume encyclopedia on the genre—community cookbooks are usually recipes collected by groups, such as churches, schools, and social clubs, organized into a book, and sold to raise money. They’re also known as fundraising cookbooks, charitable cookbooks, church cookbooks, or, simply, “those spiral-bound books,” Lindgren says.

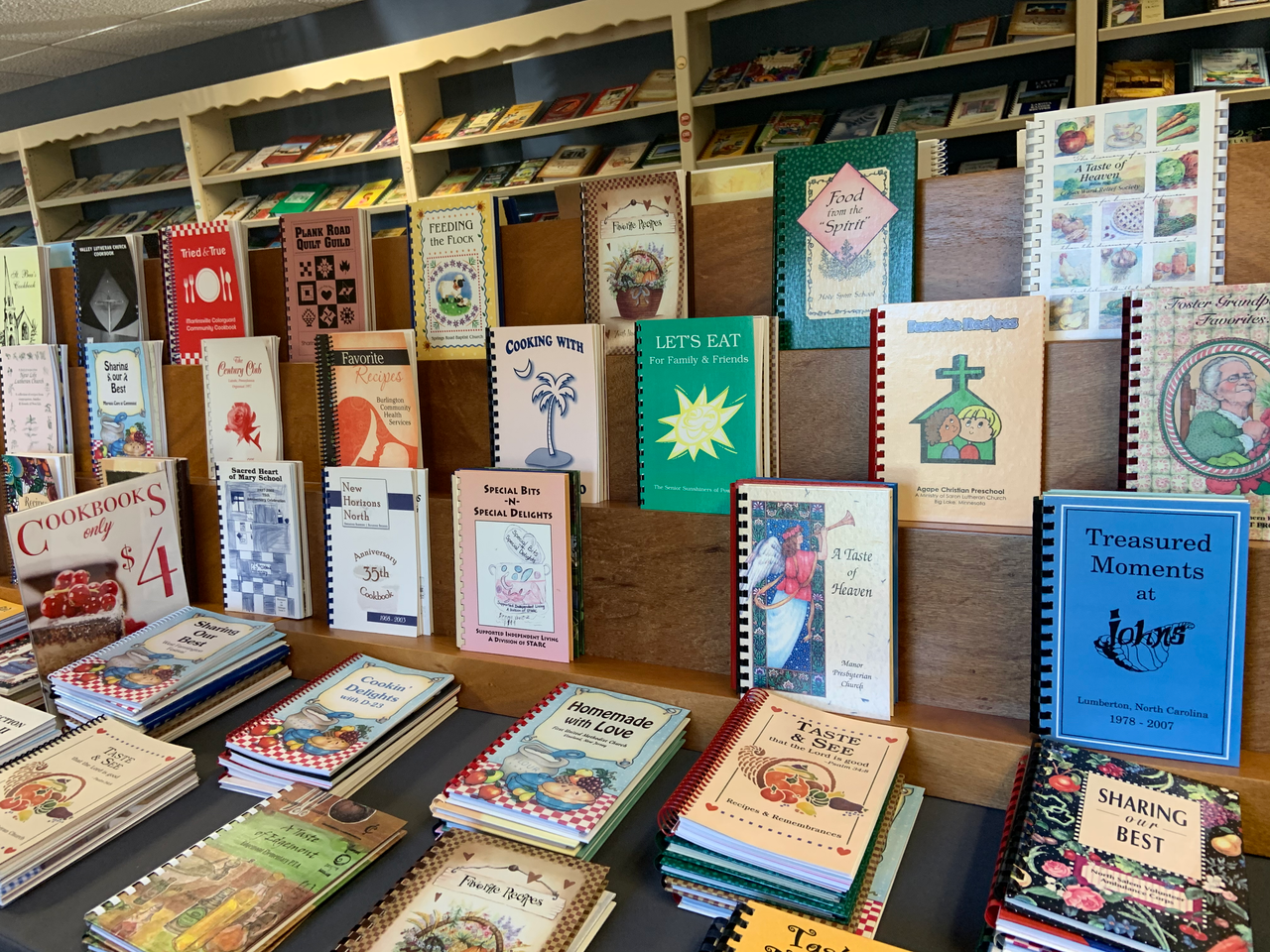

The Morris Press headquarters is a small gray building that houses the company offices, its printing and binding equipment, and an on-site bookstore that sells surplus cookbooks from fundraising efforts across the country. Ryan Morris, the fourth generation of his family to run the company, spreads an array of titles across a conference room table to show me. Illustrations of country singers, athletes, aquarium staff, and sailors stare out from the covers.

As a pay-to-publish operation, the company very rarely turns prospective authors away, which means their catalog is vast and colorful. At more than 60 million books printed and 150,000 unique titles published, “you name it, I’ve seen it,” Morris laughs. They’ve published cookbooks by soap opera stars, the Chicago Bulls, and even a collective of gay clowns in San Francisco. (Note: Morris did not have the gay clown cookbook on hand and couldn’t remember its name. If any readers knows of a group of gay clowns in San Francisco who produced a cookbook with Morris Press, please get in touch.)

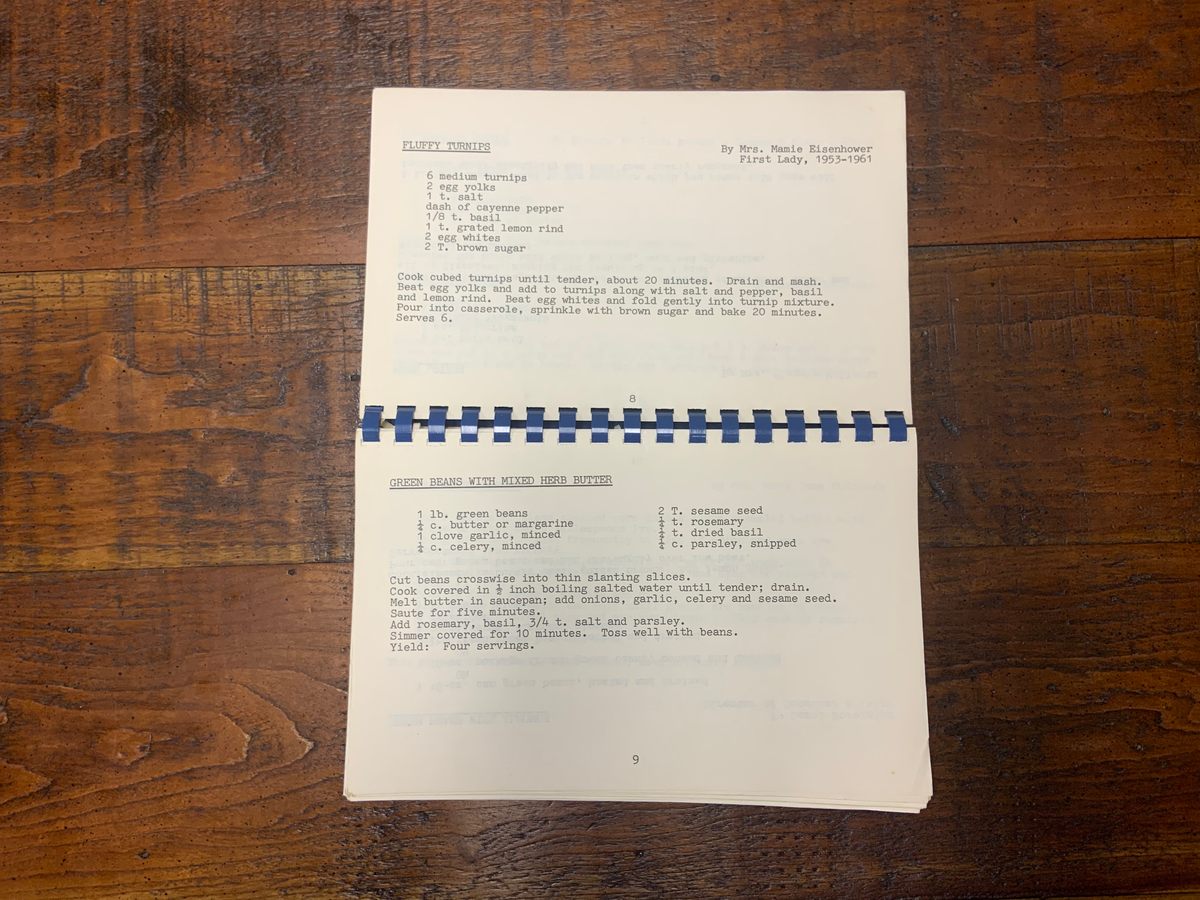

I flip open a particularly weathered spiral-bound tome, labeled Old Family Favorites, and find a recipe for “Fluffy Turnips” attributed to First Lady Mamie Eisenhower. Mamie’s turnips, along with other recipes for salads, casseroles, and something called “Pork Cake,” were all part of the vintage cookbook’s campaign to raise money for the Nebraska Council for the Aging. Another title, Go Big Red: Recipes and Traditions From the Hearts of Huskers, contains recipes contributed by members of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln football team. Player photos grace each page, along with their favorite recipes, ranging from fullback George Sauer’s Hot Chicken Casserole to offensive guard Randy Schleusener’s carrot cake.

Morris’s own favorite publication in the archives is a cookbook based on the early ’90s sitcom Evening Shade, starring Burt Reynolds. The book features recipes from Reynolds, as well as “friends of Evening Shade,” which somehow included Bill and Hillary Clinton.

Morris Press opened its doors as a small printer and office-supply store in the 1930s. Their cookbook focus was a later development. But the history of American community cookbooks stretches back into the 19th century. Lindgren cites Nantucket Receipts, a Boston cookbook published in the 1870s to raise funds for a local hospital, as the country’s first community cookbook. He attributes the birth of these hyper-local publications to advancements in printing technologies and kitchen tools that expanded the range of what cooks could make at home.

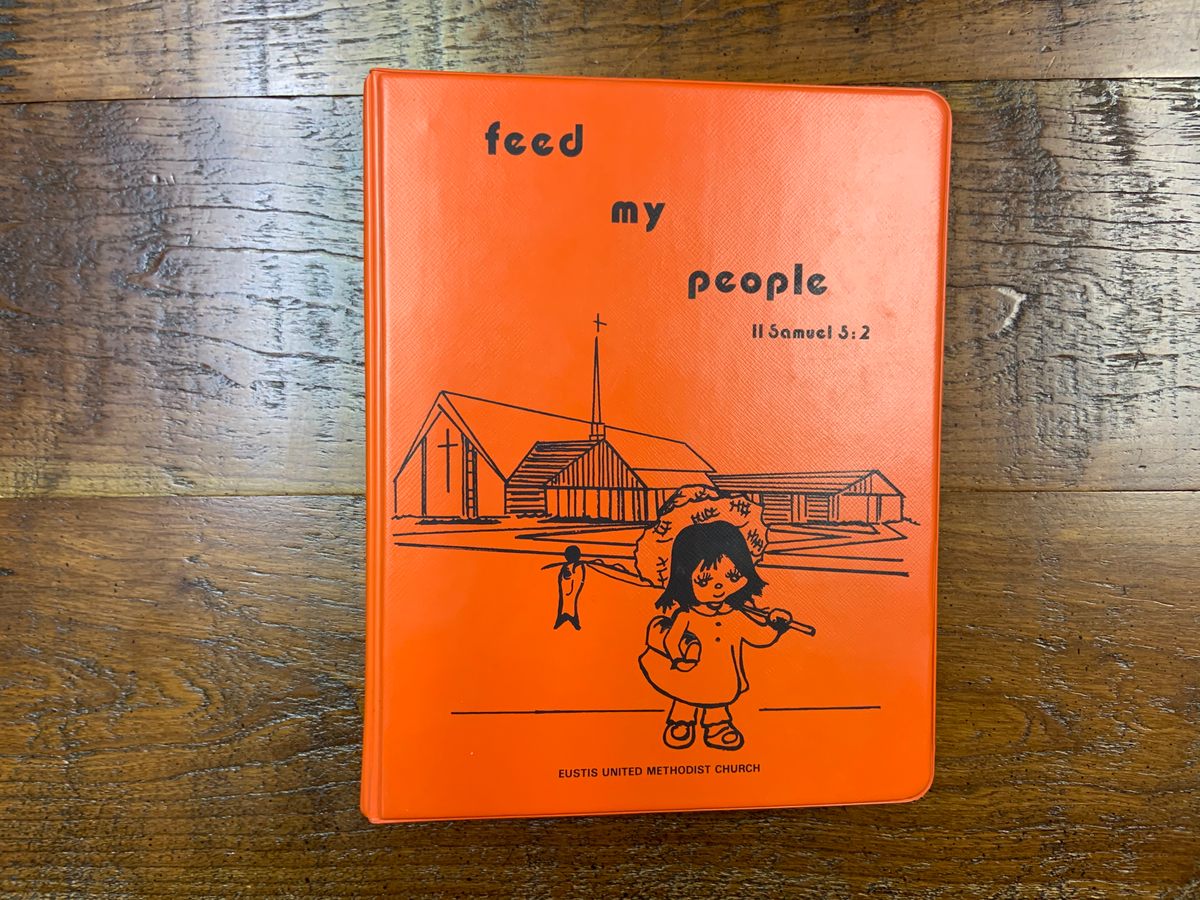

Traditionally, community cookbooks have been the purview of church groups. Morris knows this well. He remembers traveling the country to attend religious conventions with his parents as a child. His father attended to hand out sample cookbooks and brochures. In the conference room in Kearney, Morris shows me Feed My People, an undated orange vinyl-covered cookbook by the United Methodist Church of Eustis, Nebraska.

Feed My People includes recipes for everything from orange cake to German fare. But, as is often the case with community cookbooks, it holds more than just recipes. The book opens with an introduction titled “What is a United Methodist Woman?” The definition is, fittingly, food-focused: “She is COMFORT with a casserole in her hand, SERVICE sweeping up wedding cake crumbs, COMPASSION with her pledge card in her pocket, FRIENDSHIP with a cheerful smile on her face, and a hunger for knowledge armed with her bible and a study book.” (She also, apparently, had the “energy of a pocket-size atomic bomb.”)

Feed My People’s self-congratulatory introduction hints at the unexpected power community cookbooks afforded women. In the era before larger publishers like Morris, a community cookbook’s printer was often a neighbor or another member of the church congregation. Since they could simply barter with a fellow churchgoer over printing fees, for example, women didn’t need to involve their husbands in negotiating contracts. And since the books proved an incredibly effective fundraising tool, they also provided women with the money to effect change in their communities.

The informality of this process, though, has presented a challenge for culinary historians. Lindgren has pored over church records to try and piece together the financial impact of the books. While men are always named in said records, the women are often recorded only with the initials of their social clubs. “This was to sort of hide the fact that these women were raising all this money,” he says. “They would never name them, but they would put these little acronyms … And you’d look and you’d see that 62 percent of the money for the new steeple was raised by them.”

Whether it was building a library, expanding a hospital, or repairing a church steeple, funds raised by community cookbooks gave women an opportunity for civic engagement previously denied to them. (It should be said that “women” here largely refers to white women with the resources to produce them, though African-American women also created cookbooks for fundraising in the early 20th century.) Some women even parlayed this agency into feminist causes: More than one suffrage-promoting cookbook appeared prior to the passing of women’s right to vote.

The informality of local publishing also came with unpredictability. Local printers dwindled in the 1890s, as smaller presses consolidated into larger companies. Many community cookbook makers scrambled for alternatives. According to Lindgren, some went the DIY route, employing whatever resources they had at their disposal, hand-sewing book spines and binding them with silk thread and ribbon, and covering them in oilcloth, wallpaper, or even linoleum.

The result was a patchwork of beautifully crafted tomes released from the turn of the century through the 1920s. By the next decade, those who didn’t want to bind their books in linoleum finally had another option: the specialty community cookbook publisher. While Morris is the lone remnant of this niche industry, there were once several presses in the central United States that offered affordable, simple community cookbook templates. This approach may have reduced the incredible ingenuity of the earlier years, but the more accessible publishing option helped democratize the community cookbook, pushing it outside the domain of church fundraisers.

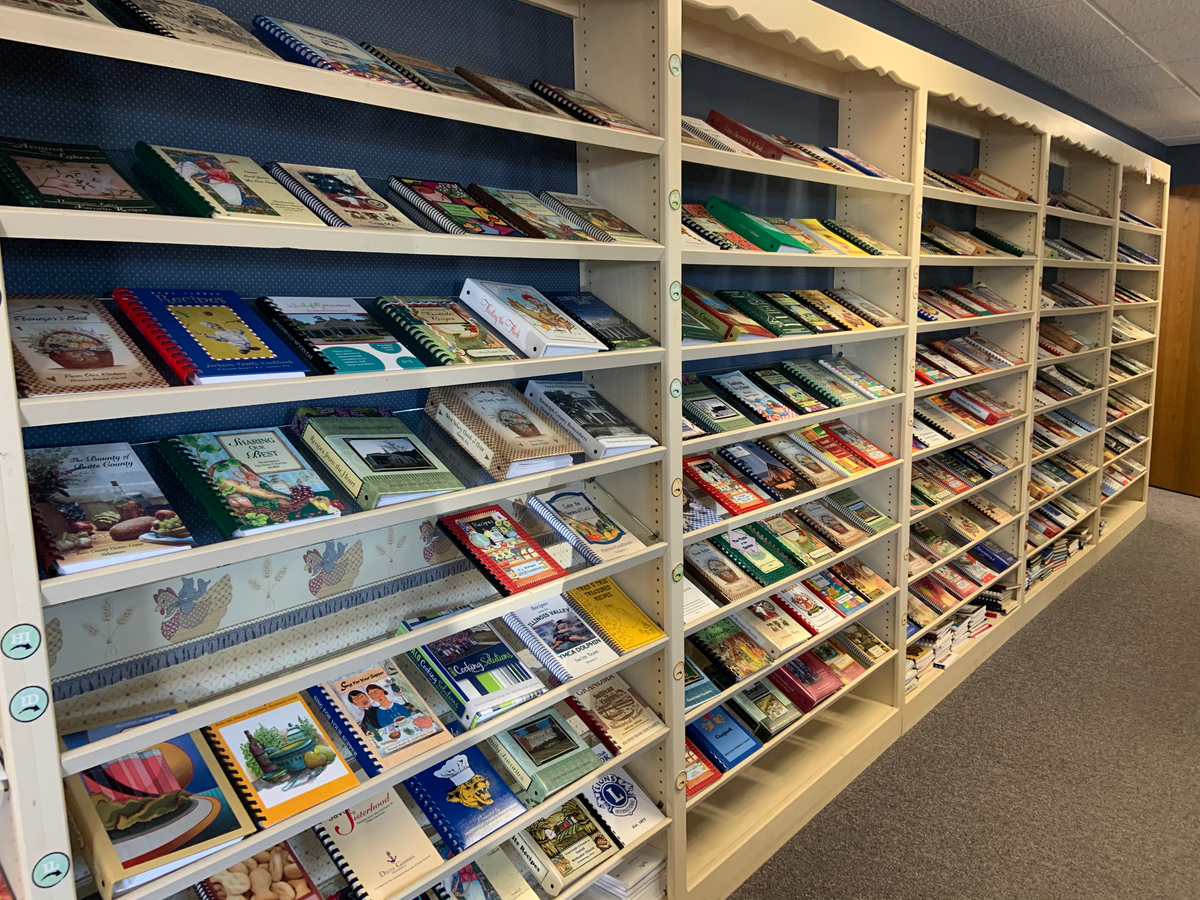

As a result, nearly every social group in the United States has published a community cookbook. In her 24 years working as a proofreader and running the Morris Press in-house bookstore, Cindy Schneider has seen, and sold, books by everyone from cemetery associations to quilting clubs. “I have a warped sense of humor,” she laughs as she shows me From Our Solid Waste Family to Yours, a cookbook published by a Texas sanitation department. She’s organized the company’s storefront into several sections: a whole wall of state-by-state cookbooks (she’s all out of Hawai’i, a hot commodity), local cookbooks (such as cowboy recipes by a Kearney artist, whose Western-themed paintings hang on the office’s walls), single-focus cookbooks (including annual books for blueberry and strawberry festivals), animal-themed cookbooks (there’s more than one cookbook called Bone Appétit published by humane society chapters), church cookbooks, and family cookbooks. If you ask nicely, Schneider will even pull some rare titles out of the back, including what she calls a “real naughty” erotic cookbook.

But beyond the silly and risqué titles, there are also deeply moving books on the shelves. With the decline in church attendance and rise of other fundraising options like GoFundMe or Kickstarter, Morris notes that the company now markets cookbooks as personal keepsakes as well as fundraising engines. The family section of the bookstore is particularly touching, filled with anniversary cookbooks commemorating a couple’s lifetime of cooking together and wedding cookbooks uniting two families’ culinary traditions into one tome.

It might be the personal touch that has allowed Morris to survive into the Internet Age. No matter how delicious, a recipe downloaded to your phone can’t quite offer the same effect as an old spiral-bound book featuring fluffy turnips from a former First Lady. Despite the struggles of print media, and the rise of celebrity chefs, food blogs, and digital publishing, Morris boasts that all of their cookbooks still turn a profit.

Most of that money, of course, goes to the communities and their fundraisers. For Schneider, the charitable purpose of the books she helps publish and sell is one of the most meaningful parts of the job. “I’ve cried more than once looking at some, you know,” she says. Gesturing to the wall of small, brightly colored cookbooks on display in the store, she mentions one memorable book, published to raise money for a child with leukemia. “They’re touching.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook