The Challenges of Reclaiming Filipino Louisiana’s Centuries-Old History

Members of what is perhaps the oldest Asian community in the United States are committed to preserving—and sharing—their story.

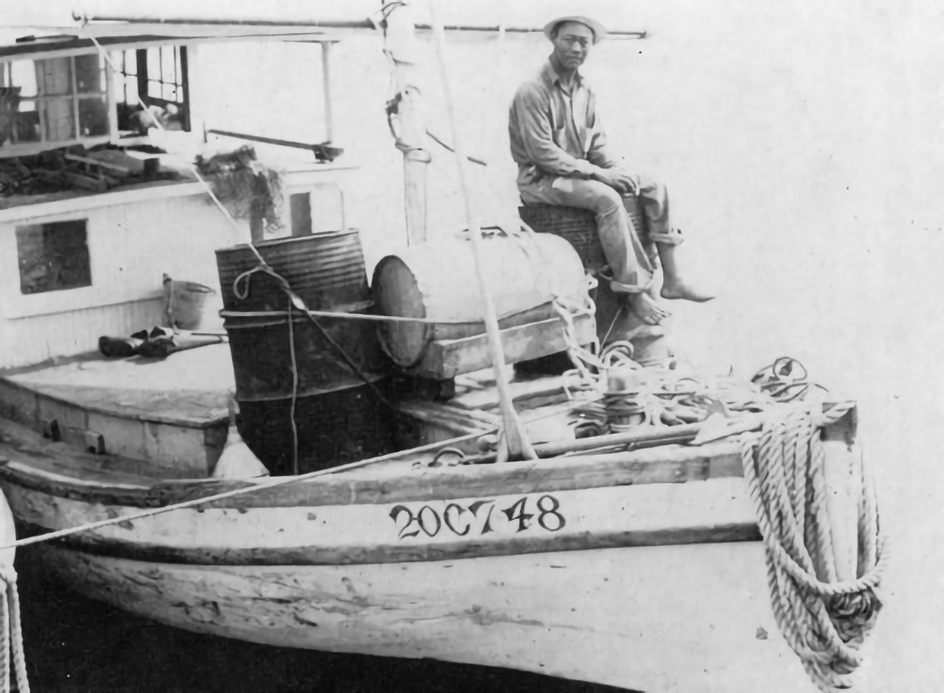

In 1883, an Italian-crewed lugger moved slowly through the shallow, murky waters of the Louisiana bayou. At times the men aboard used poles, or grabbed onto muddy banks with their bare hands, to push the small ship through the swamp amid a cacophony of frogs and insects.

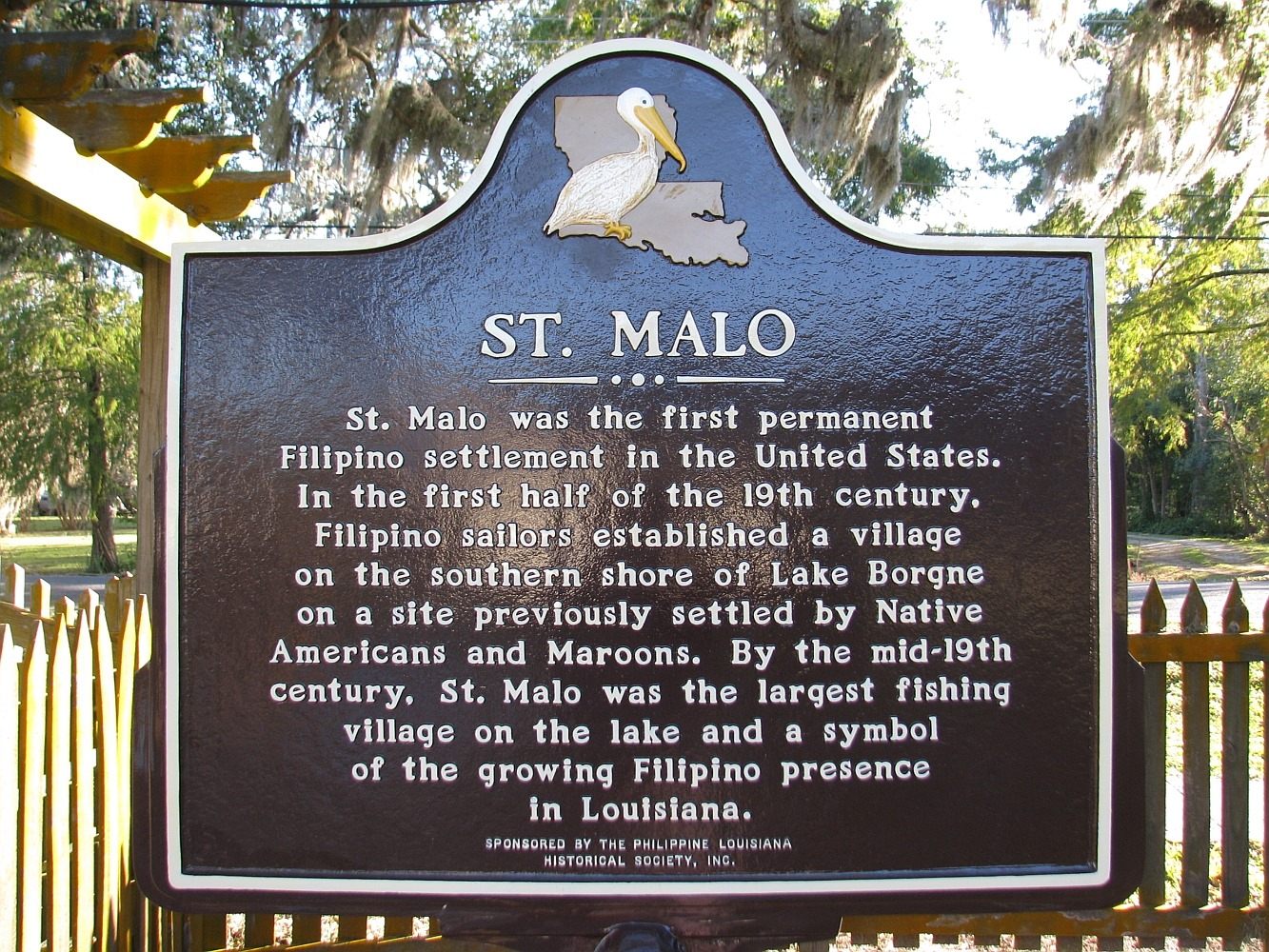

A day’s journey east from New Orleans, Lafcadio Hearn, a correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, saw the first steep-roofed houses rising on stilts above the green waters of Lake Borgne. The lugger and its crew had arrived at a place few outsiders ever visited: the Filipino village of St. Malo, perhaps the oldest Asian community in the United States. By the time Hearn arrived, it had stood for generations.

In his report on the visit, Hearn has the dismissive tone of an outsider: “But for the possession of modern fire-arms and one most ancient clock, the lake-dwellers of St. Malo would seem to have as little in common with the civilization of the 19th century as had the inhabitants of the Swiss lacustrine settlements of the Bronze Epoch.”

Indeed, the history of Louisiana’s Filipino community has been largely written by outsiders—when it has been written about at all. In a state where Acadian and West African heritage sites and communities are celebrated, St. Malo and other early Filipino villages are rarely mentioned, though they are among Louisiana’s oldest.

“People in power tell the stories, and Filipinos weren’t in power,” says Randy Gonzales, an English professor at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. “It wasn’t malicious, they just didn’t think about it any other way.”

Gonzales, a fourth-generation Louisiana Filipino, is among a handful of people in the community uncovering and reclaiming their history. Like navigating the bayou, it is not an easy course. Separating fact from myth remains a challenge, and much of the evidence has been lost. St. Malo, for example, was destroyed by the New Orleans Hurricane of 1915. In 2019, community members erected a marker 30 miles east of New Orleans, but the exact location of the village, like its date of origin, remains a mystery. Retrieving the early history of a community that settled in these swamps more than two centuries ago, and left no written record, requires both creativity and caution.

“In terms of Filipinos coming here, the biggest question we had was why?” Gonzales asks. The answer lies in an old empire. The Philippines’ Spanish overseers, in power since 1565, “weren’t interested in educating, so there weren’t many opportunities in the Philippines,” Gonzales says. When Spain acquired Louisiana from the French in 1763, people from around the empire, including the Philippines, began trickling into the colony. “Louisiana provided opportunities for these early migrants,” says Gonzales. “There was a comfort level to the culture of Louisiana; people spoke Spanish and practiced Catholicism.”

The Mississippi Delta’s brackish backwaters abounded with shrimp, and Filipino fishermen found they faced little competition in the deep bayou. St. Malo became a launching point for fishing expeditions to even more remote sites. Facing malaria, heat, and hurricanes, these early settlers made their living from shrimping; the wealthiest among them married into surrounding communities and educated their children in New Orleans.

Felipe Madriaga was one of hundreds of Filipino seamen drawn to St. Malo. Born around 1815 in North Luzon in the Philippines, he established himself as a sailor in Liverpool, and crisscrossed the Atlantic before eventually settling in St. Malo with his wife, an Irishwoman named Brigette Nugent, in 1846.

Rhonda Richoux is a sixth-generation descendent of Felipe Madriaga, and her family has lived in Louisiana for almost two centuries. “Felipe and Brigette had three daughters, so the Madriaga name did not pass on,” says Richoux. “I follow my matrilineal line from Brigette all the way through to my mom.”

Richoux has played an essential role in preserving Louisiana’s Filipino history, not just as a researcher but also as the inheritor of a remarkable family story. “There are other Filipino families that predate us, but they don’t know any of their history,” Richoux says. “The fathers in our family always made the daughters marry men from the Philippines, which is why we kept our identity for so many generations.”

Richoux grew up listening to her great-grandmother, one of the last people to have known Felipe Madriaga. Through her, Richoux connected with generations of settlers who came before. “My great-grandmother told me her grandfather Felipe said that Filipinos had been at St. Malo at least 50 years by the time he got there,” she recalls, “but that isn’t written in stone.”

St. Malo’s age is in fact one of the most contentious questions in Filipino Louisiana story. The first person to attempt a complete history of the community was a Filipino immigrant and university librarian named Marina Espina. Richoux met Espina at a Filipino club in New Orleans in 1967, shortly after Espina’s arrival. “She joined our club so that she could meet local Filipinos,” Rhonda recalls. “She had been there a while when she sat down with my grandma and started talking about the family. She said, ‘What? Y’all had been here since when?!’”

Espina published the book Filipinos in Louisiana after two decades of research. Drawing on troves of previously unshared testimonies and documents, she claimed that men forced into labor on Spanish galleons leaving the Philippines eventually, after crossing oceans, escaped into the bayou. If her account is correct, St. Malo might date back to the mid-18th century or earlier.

Gonzales is skeptical. “I don’t think the timing is right. The galleon trade ended before this time period,” he says. “The galleon trade helped make Filipinos seamen, but we don’t even know if Filipinos arrived on Spanish ships.”

Gonzales says it’s possible that sailors “jumped ship,” (a phrase often repeated in family histories), but he is concerned about the way the story is framed. “It goes back to the idea that Filipinos deserted, which goes back to the idea that the Spanish had power over them. The narrative emphasizes the Filipinos as labor, and not as individuals free to move as they pleased.”

Richoux disagrees. “Some historians say that Espina made assumptions about the galleon trade. But they say the same about those of us who pass on our oral history without any proof. I think it’s possible that some of these men actually did come from the galleon trade.”

Beyond the veracity of Espina’s theory, Richoux believes her research is vital to the community. “People have to give her credit for what she did,” Richoux says. “She was the first one who discovered us.”

Sadly, much of Espina’s collection of oral histories and archival documents was destroyed in 2005 by Hurricane Katrina. Espina, now in poor health, has been unable to rebuild the lost information. Katrina robbed others of photographs and family documents as well. Richoux was devastated when the hurricane destroyed much of her connection to the past, including recordings of her grandmother’s memories. “I’m afraid of that ever happening again, and all the information about my family being lost,” says Richoux. “I don’t want people to forget that Filipinos have been here for a very long time.”

While they disagree over the community’s origins, Richoux and Gonzales are collaborating to promote what they know of their history. “The goal is to get into Louisiana textbooks, to make Filipinos in Louisiana part of the story that’s told to young people,” says Gonzales. “Filipinos in Louisiana are always being ‘discovered.’ Someone will write an article, ‘I bet you didn’t know there were Filipinos in Louisiana!’ Ten years later, someone will write the same article. I wish that would stop one day.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook