Harnessing the Dystopian Dread of the Brutalist Tower Block

The real-life British buildings behind J.G. Ballard’s harrowing “High-Rise.”

This story is excerpted and adapted from Phyllis Richardson’s House of Fiction: From Pemberley to Brideshead, Great British Houses in Literature and Life, published in May 2021 by Unbound.

Housing in postwar Britain was anything but romantic. The necessity of building, and quickly, shelter to replace the 100,000 houses destroyed by the Blitz in London alone, meant there was little room for romance. Coming to England as a teenager in 1946, after having been raised in the Shanghai International Settlement and spending two years in a Japanese internment camp, novelist J.G. Ballard described it as “a terribly shabby place.” It was, he said, “locked into the past and absolutely exhausted by the war.”

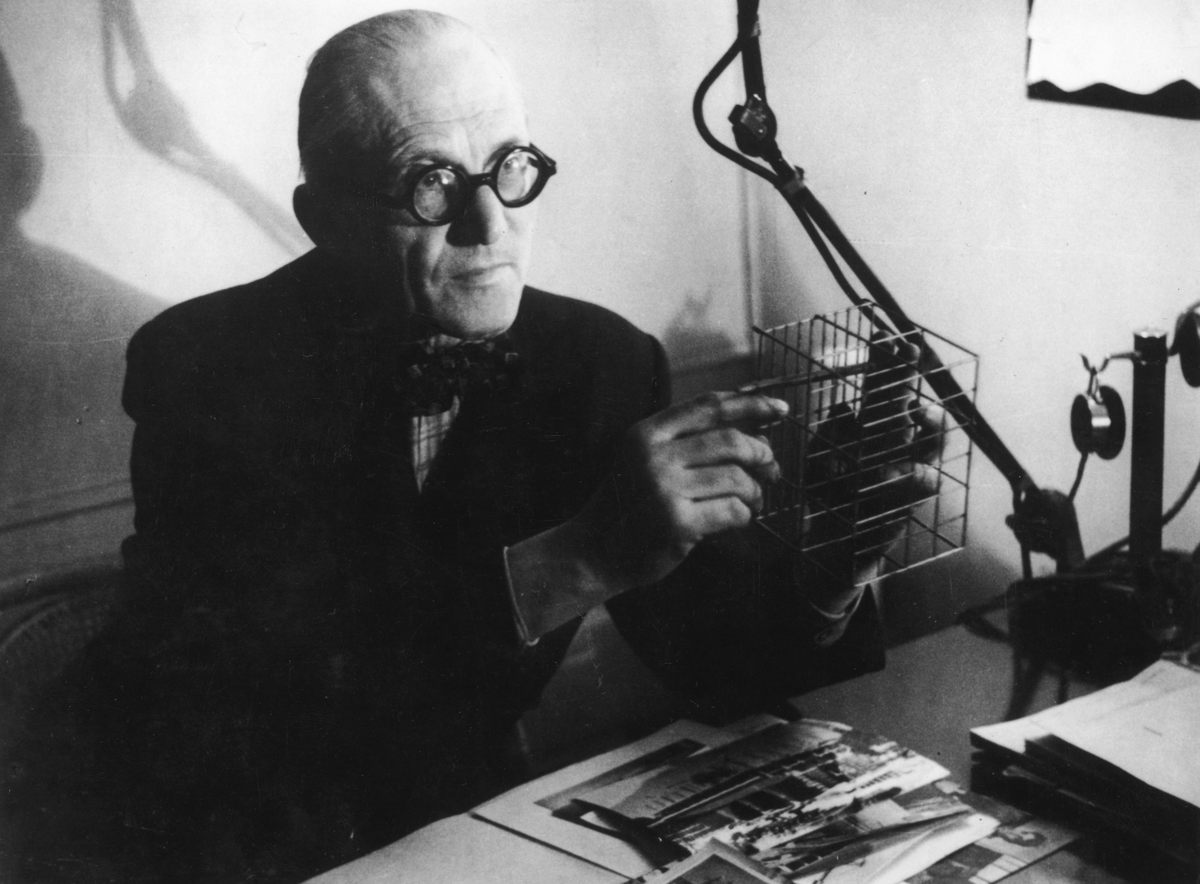

In that aftermath, some architectural and planning theorists saw a clean slate on which to begin anew with modern ideas and advances in technology and ways to create new towns and solutions to urban and suburban housing. “Utopian modernists,” such as Le Corbusier, believed that advances in technology and engineering could produce forward-looking architecture that would promote essentially socialist ideals of offering beneficial housing to all. This attitude, combined with the need for high-density housing, resulted in the construction of what are now called tower blocks in Britain: apartment buildings of multiple stories that might also include other amenities, such as common space at different levels, with shared walkways and stairs dubbed “streets in the sky.” Packing many more people into a smaller footprint and offering all the modern conveniences, these models had great appeal for housing chiefs and a tremendous impact on postwar building. The first tower block was built in London in 1954, and by the end of the 1950s half a million new flats had been built, many of which were in new “mixed” developments that included multistory blocks.

In 1975, Ballard published a novel that focused on these London developments, marrying consumerist ideals of luxury housing with the social problems caused by crowded urban environments. High-Rise begins with 2,000 hopeful residents entering a 40-story apartment tower with smooth, modern design and high-end conveniences, feeling that they have bought into a life of domestic ease. However, the novel ends with the dwellings, halls, shops, and corridors being devastated by a brutalism that has less to do with architectural design than with the human malevolence it has somehow inspired.

Ballard makes clear his antipathy for the development. The apartments are described as “cells” in the cliff face. Rather than being a beneficent “machine for living in” (in Le Corbusier’s words), the building is “a huge machine designed to serve, not the collective body of tenants, but the individual resident in isolation.” Its array of services—air-conditioning, garbage chutes, electrically operated features—were all things that “a century earlier” would have required “an army of tireless servants” to provide. It is a pointed irony, then, that the architect who dresses largely in white and lives in the penthouse at the top of the building, like some “fallen angel,” is married to a woman who grew up in a country house and is at first uncomfortable in the building’s automated and cloistered lifestyle.

The flats in Ballard’s dystopia are occupied not by social-housing tenants, as in the tower blocks that were dotted around London and other U.K. cities by this time, but by “professionals,” who are nonetheless grouped by of wealth. The lower nine floors are “home to the ‘proletariat’ of film technicians, air-hostesses and the like,” while the middle section, up to the 35th floor, is made up of “docile members of the professions—doctors, and lawyers, accountants and tax specialists.” The top five floors contain “the discreet oligarchy of minor tycoons and entrepreneurs, television actresses and careerist academics.” This last group has access to the high-speed lifts, carpeted stairs and “superior services.” It is not difficult to foretell how grievances might erupt in a building that is seen by its residents as both “a hanging paradise” and a “glorified tenement.”

Robert Laing, a physiology lecturer, is one of the main protagonists of the story, and has his first hostile encounter involving a dispute over the shared rubbish chute. As he negotiates the social strata of the building, he soon realizes that “people in high-rises tended not to care about tenants more than two floors below them.” Glitches in the building’s electricity supply and malfunctions in some of the lifts servicing the lower floors ignite an internal class war. Unpleasant confrontations in the public spaces rapidly escalate into physical violence. Like most of the residents, Laing becomes drawn in, rather than repelled, by the growing depravity as tenants raid each other’s apartments and are reduced to the “three obsessions” of security, food, and sex. Ballard describes clashes taken to surreal extremes, arguing that the building itself demanded this behavior, being “an architecture designed for war, on the unconscious level if no other.” The relentless narrative catalogues scene after scene of primal beings battling through apartments that have been torn apart and barricaded, where mounds of rubbish line every space, and where domestic animals are killed for food.

Ballard, who was no admirer of England’s “green and pleasant land” and was quick to embrace the cool promise of modernity after the war, nevertheless found worrying portents in the high-rise tower blocks going up in cities in the United Kingdom and United States. In London, the buildings that had promised so much were proving to be problematic, attracting crime and vandalism and sometimes failing to function. The idea of “streets in the sky” with amenities at different levels, moving living space into the vertical, had demonstrated worrying cracks and earned swathes of vocal detractors. Ballard never cited these projects directly, but he claimed to have carried out his own research into criminal behavior and concluded that a “degree of criminality is affected by liberty of movement; it’s higher in cul-de-sacs. And high-rises are cul-de-sacs: 2,000 people jammed together in the air.”

Although Ballard never made direct comparisons between the novel and the Brutalist towers that were going up during the time he was writing, those buildings certainly can be seen as structures that are better off with “man’s absence.” As pristine edifices they can appear pleasingly sculptural, but are less so when their balconies are dotted with the detritus of everyday life, and further degraded by poor maintenance, graffiti, and general neglect. Ballard’s environments of uniform luxury become dehumanizing, but rather than engendering mindless conformity, as in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, they result in “the regression of middle-class professionals into a state of barbarism.”

The novel is often associated with Trellick Tower, a Brutalist 31-story block in Kensington designed by architect Ernő Goldfinger, which by the time Ballard was writing High-Rise had had a series of problems and a lot of bad press. Even before its opening, there were crises, both in its own construction and in other projects. In 1968, a fire in the Ronan Point tower block in London caused most of the 23 floors to collapse and the deaths of three people. The disaster fueled popular agitation against tower blocks, so that by the time Trellick Tower was completed in 1972, it seemed doomed to fail. The “drying rooms” that Goldfinger had designed in the ground-floor amenities block were vandalized before they were finished. These rooms were his attempt to convince the tenants not to air their laundry on the balconies (and so ruin the appearance of the tower), but they never functioned properly. Just before Christmas 1972, a fire hydrant on the 12th floor was tampered with, causing flooding through the elevator shafts, which meant that the block had no water, heat, or electricity during the holidays. The tower became so firmly linked with crime and social decay that some council-housing tenants lobbied not to be housed there. (It should be noted that at least some of Goldfinger’s assumptions were correct: In the 21st century, improvements in maintenance and security have made the Trellick Tower a desirable address.)

Rather than making his fictional model a replication of social-housing schemes, or naming any of the council-run tower blocks as inspiration, Ballard set his story in a deliberately upscale version, citing its genesis in his experiences of luxury high-rise living in London and abroad. He described a complex of office and residential blocks in his parents’ neighborhood near Victoria, which were, he said, mostly inhabited by “rich business people” with “Rolls-Royces and immodestly appointed flats, huge rents.” Yet the residents, he said, “spent all their time bickering with one another” over issues of “the most incredible triviality,” such as who needed to pay for a potted-plant display on the 17th-floor landing and whose curtains didn’t match. He found similarly petty grievances rising among tenants in an upscale apartment block where he stayed on the Costa Brava in Spain. Again, these were mostly occupied by educated professionals, but Ballard reported “an enormous amount of antagonism between the people in the lower floors and the people in the top.” Interestingly, Ballard placed the shops and amenities for his high-rise on an intermediate floor (the 10th), as Le Corbusier had done in his ground-breaking utopian model, the Unité d’Habitation in Marseilles, which becomes another cause of tension between the residents in the novel. Goldfinger felt that locating services up inside the building would be detrimental to residents on lower floors, and so at Trellick Tower he chose to place these amenities—nursery, doctor’s surgery, laundry—at ground level.

Another immediate provocation for the high-rise setting of the book probably came from the development of the London Docklands at about the time that Ballard was writing. Developers were attempting a regeneration of land among the old warehouses and abandoned shipping yards of a long-desolate waterfront district by introducing a scheme of high-rise towers for office and residential use. The first tower in this development was finished in the 1980s, but plans had already been underway for ambitious building projects in the disused ports since the early 1970s. Ballard specifically sites his fictional tower in a square mile “of abandoned dockland and ware-housing” in London, so the Docklands development provides some ambient background. But Ballard seems particularly keen to demonstrate that the luxury high-rise is as prone to criminality as its less fortunate relations in subsidized estates. In fact, the professional classes in the world of Ballard’s imagining become more deviant, relishing their descent into inhumanity as more buildings are finished and occupied around them. The five towers in the fictional development overlook an ornamental lake, which remains an empty concrete basin (a sign of promise unfulfilled), while the tenants of the first tower fall into savagery reminiscent of the adolescent boys in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, an equally disturbing fable of human depravity.

Ballard’s more extreme scenarios may be in the realm of science fiction or fantasy, but his underlying assertion that the vertical container for living could have a serious social and psychological impact are not so easily dismissed. His decision to focus on a luxury high-rise inhabited by the educated and the wealthy, rather than on the typical tower blocks built for social housing, was perhaps to make the point clearly that it was the design of the building, not the class of the residents, that brought about such a hellish downward spiral of human behavior. It is a telling irony that in Ballard’s technologically advanced high-rise, warfare is ignited largely by an everyday facilities failure: the breakdown of the lifts.

As an adult and father of three children, Ballard himself lived most of his life in England, in “a little suburban house” in Shepperton. He remarked that journalists who turned up to interview him were often surprised, as they were “expecting a miasma of drug addiction and perversion of every conceivable kind,” but instead found this “easy-going man playing with his golden retriever and bringing up a family of happy young children.” The madness, it seems, was securely locked up in the high-rise.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook