Five of the Greatest Art Saves of World War II

War is a time of destruction, and many of the pieces of art or architecture that survived during World War II were saved by the courageous souls in the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program. The initiative of the Allies — known as the Monuments Men, focus of a forthcoming film — was a team of 400 soldiers and civilians working to protect cultural heritage, and recover art looted by the Nazis

Below are five of the greatest art saves from World War II, where ordinary people and the MFAA both strove to save this heritage amidst the battles.

The Mona Lisa

Mona Lisa revealed after the war (via louvre.fr)

Few in the crowds that now mob Leonardo da Vinci’s “Mona Lisa” in the Louvre know how much she traveled during World War II. As the war was breaking out, the greatest treasures of the Paris museum were boxed up in waterproof materials and send to the countryside. After departing the Louvre on August 28, 1939, the “Mona Lisa” moved five times, including to Loire Valley castles and a quiet abbey, all the while that enigmatic smile masked inside a plain wrapping. It must have been a relief when after the war she returned to Paris and that famous face was glimpsed again.

“The Winged Victory” being relocated during the art evacuation of the Louvre (photograph by Pierre Jahan/Archives des musées nationaux)

The Last Supper

“The Last Supper” before World War II (via witcombe.sbc.edu)

The “Mona Lisa” wasn’t the only Leonardo da Vinci masterpiece to have a close call during World War II — the “Last Supper” fresco was almost blown to smithereens. The mural on the wall of the Santa Maria delle Grazie church in Milan was carefully covered with sandbags and scaffolding, which is likely what saved it when Allied bombs pummeled the city on August 15, 1943. Almost all of the church was turned to rubble in the air raid, yet improbably standing among the debris was the wall with the “Last Supper.”

After the air raid, with “The Last Supper” behind the scaffolding on the right (via monumentsmen.com)

The Prinzhorn Collection

1909 letter by mental patient Emma Hauck, part of the Prinzhorn Collection (via Wikimedia)

One of the lesser-known art saves of World War II is the Prinzhorn Collection. The collection in a university psychiatric clinic in Heidelberg was amassed by Hans Prinzhorn, an art historian and practitioner of medical science during World War I, who took a particular interest in how mental illness was manifested in art. The around 5,000 pieces from some 450 patients would likely have been destroyed by the Nazis who eradicated Europe of much “degenerate” art that fell outside their ideas of perfection. However, the art was hidden away in university storage and is now out on permanent display today in the clinic.

“Witch’s head” (1915) by August Natterer, who had schizophrenia, part of the Prinzhorn Collection (via Wikimedia)

Altarpiece of Veit Stoss

Detail of the Veit Stoss altar (via Poland Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Created in the late 15th century by Veit Stoss, the altarpiece of St. Mary’s Basilica in Krakow, Poland, is the most massive Gothic altarpiece in existence, but its reign of beauty almost ended during World War II. Polish citizens had taken apart the lime wood altar and hidden it in different crates across the country, but once Poland was occupied these containers were tracked down and shipped to Germany. There they ended up in the basement of Nuremberg Castle, which was totally wrecked by bombs. Yet Polish prisoners there had alerted the Polish Resistance of the altar’s presence, and despite all odds it was found intact in the untouched basement. It returned to Poland in 1946 and looms beautifully over the church today.

The altar in the church (photograph by Jorge Lascar)

Salt Mines of Altaussee

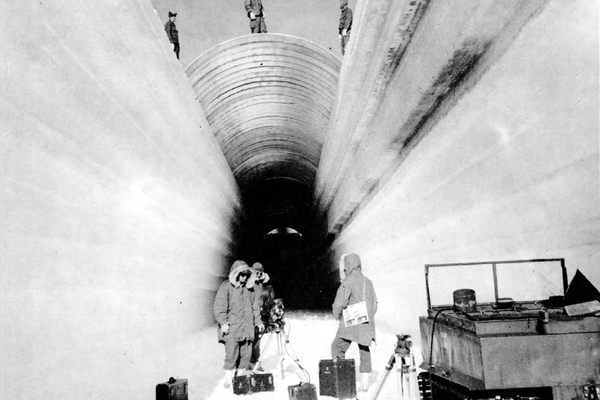

At the mines in 1945 (via Wikimedia)

Hitler had grand visions for a “Führermuseum” which would house all the wonders of European art — and for this he looted the best museums he could. Much of the art intended for his dream museum ended up in the Austrian salt mines of Altaussee, including works by Michelangelo and Vermeer, along with Jan van Eyck’s stunning Ghent altarpiece. The mines were actually intended to be blown up — with all 6,500 paintings inside — upon an Allied advance, but something prevented the explosions. Eventually the American army with the MFAA Monument Men took control of the mines, although sorting out where all the art goes is still an ongoing project.

The Ghent altarpiece recovered from the mine (via Wikimedia)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook