These Strange Rock Formations Have Been a Filmmaking Hotspot for Over a Century

California’s Alabama Hills have stood in for multiple states and countries, not to mention distant planets, alternate dimensions, and fantasy realms.

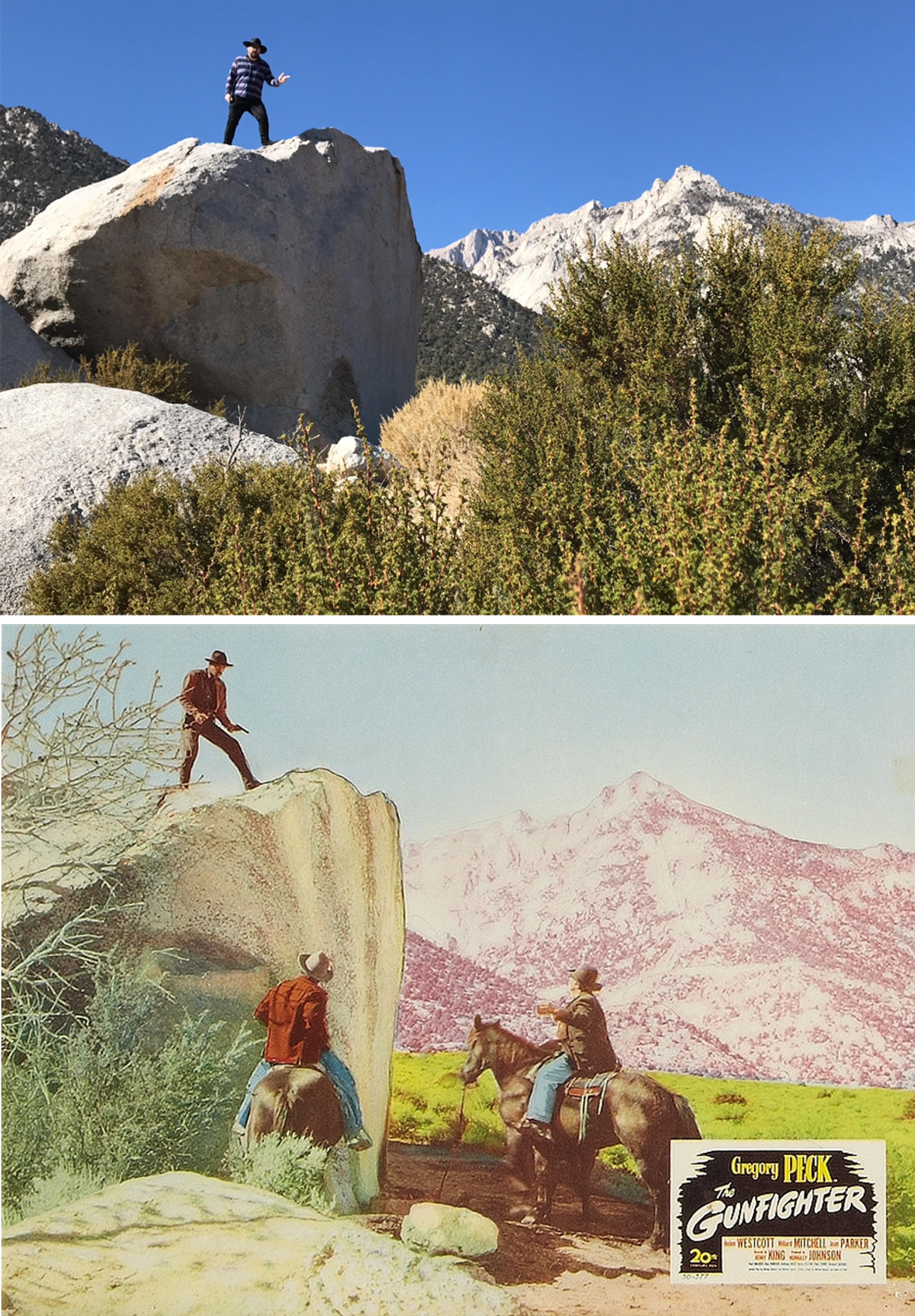

Located in Central California, just west of the town of Lone Pine, the Alabama Hills are one of Hollywood’s least famous but most filmed stars. Less “hills” and more giant huddled masses of stone, they are identifiable by the surprising smoothness of their rounded contours, which creates a gorgeous contrast with the sharp lines of the Sierra Nevada mountains that form their backdrop. Though this landscape is truly unlike anywhere else on Earth, its uniqueness hasn’t hindered the diversity of the roles it gets to play onscreen.

These strange rock formations are versatile actors, having played Colorado, Arizona, Wyoming, Mexico, Spain, Iran, Afghanistan, India, and China—not to mention distant planets, alternate dimensions, and fantasy realms. It would be impossible to list all the screen legends that have shared scenes with these majestic bowed rock arches and potato-shaped stones, but they include Spencer Tracy, Errol Flynn, Clint Eastwood, Lucille Ball, Cary Grant, Cesar Romero, Natalie Wood, and Russell Crowe.

As of 2019, it’s been 100 years since the earliest confirmed filming in the area. Though The Round-Up, starring Fatty Arbuckle with a small cameo by his friend Buster Keaton, is often described as the first movie made in the Alabama Hills, it is merely the oldest known surviving film shot there. It was filmed in January 1920 and opened in theaters later that year. But two other movies released earlier in 1920—Water, Water Everywhere and Cupid, the Cowpuncher—were actually shot there the previous year, in 1919; both are now considered lost films.

Filmmaking around the Alabama Hills swelled throughout the 1920s. By the 1930s, the area had already become one of the most utilized sites for location filming outside the Studio Zone (the 30-mile radius around Los Angeles). It is up there with the Iverson Movie Ranch and John Ford’s beloved Monument Valley for shaping our collective cultural image of the Wild West. Nearly every major Western actor of the 1930s, 40s, and 50s rode their horses amid these rocks: John Wayne, Gregory Peck, Gary Cooper, Gene Autry, Tom Mix, Randolph Scott, Robert Mitchum, William Boyd, Roy Rogers, and many others.

“Probably 80 percent of the movies made here are either quasi- or real Westerns,” says Chris Langley, the Inyo County Film Commissioner. However, Langley also points out that this has never been just a one-genre locale. Everything, from science fiction to romantic comedies and from epics to biopics, has been filmed here.

Though there are many reasons to visit the Alabama Hills—campers, hikers, rock climbers, and nature photographers are just some of the people found wandering this beautiful but seemingly forbidding land—perhaps the most intriguing visitors are those that come specifically in search of film locations. They arrive year-round to seek out sites they’ve seen on the silver screen, images burned indelibly into their imaginations. Some are professional rock researchers, looking for obscure formations from silent films that few alive have even seen. Others are amateur seekers that come to pose for pictures at the more famous sites, like the canyon where Lee Powell was ambushed in the original film serial version of The Lone Ranger or the area where Kevin Bacon pole-vaulted between rocks to avoid being eaten alive by hungry graboids in Tremors.

“It’s a little bit like treasure hunting, I think,” Langley says, though he admits that he is better at watching others find locations than at doing it himself.

The year 2019 not only marked the centennial of the first films shot in the Alabama Hills, but also another important milestone for local cinematic history: The 30th Annual Lone Pine Film Festival was held that fall. Started in 1989 as the Sierra Film Festival, the Lone Pine Film Festival presents movies shot in these hills, and after the screenings, tour guides take festivalgoers out to see the very rocks and canyons they have just watched onscreen. As “the only film festival on location,” the Lone Pine Film Festival allows attendees to become amateur location scouts themselves.

Langley has been involved from the beginning. He helped the late Dave Holland and others with that first festival. Holland is the author of On Location in Lone Pine, to this day the best book to help visitors find film locations in and around the Alabama Hills. Langley later cofounded Lone Pine’s Museum of Western Film History, which opened its doors in 2006 and now hosts the annual event.

As the festival has grown and changed over the years, new issues have arisen. “I always worry about not enough young people,” Langley admits. “A lot of our audience has died off—a lot of the people who remembered Hopalong Cassidy as kids are not around anymore or not able to come.” But the museum and its festival are always trying to make inroads into new audiences. Though the vast majority of the festivalgoers I met over the four-day event last October were indeed in their golden years, there were more people under 40 in attendance than I had imagined there would be.

“We are always trying to evolve,” Langley says as he and I wander the museum, passing by the dentist wagon Christoph Waltz drove in Django Unchained, which has a prominent place near Humphrey Bogart’s car from High Sierra. The museum hosted a Tremors event in early 2020 before the coronavirus pandemic shut everything down. And the museum docents seem as happy to direct young admirers of the Marvel Cinematic Universe to the site where Robert Downey Jr. launched the Jericho missile in Iron Man as they are to point an older Western-lover to Gene Autry Rock, where the singing cowboy posed on Champion the Wonder Horse in Boots and Saddles.

If the festival’s actual median age last October was high, the proceedings were suffused with the enthusiasm of a younger assembly. The screenings bristled with bodies in the dark. There were joyous eruptions of applause. Strangers stood around outside the auditorium arguing about silent film star Jack Hoxie. Tour guides told jokes as they walked attendees from site to site, pointing to small photos in packets they had prepared for everyone on the tour, then aiming that same finger out into the landscape. “Do you see it? The curve of the rock there? He would have been standing just to the right of it,” tour guide Greg Parker said to a group on the Hopalong Cassidy tour.

Parker has attended the last 20 Lone Pine Film Festivals. “My favorite part of the tour,” he says, “is showing exactly where a camera may have been positioned during filming to capture a specific background rock or to maximize different shooting sequences from a single location.” One attendee I met, Laura Grieve, concurs—being able to watch a film and then see exactly where the shot was taken is her favorite part of the festival. She has attended the past five years. Even a bum knee couldn’t keep her away from the rocks in 2019.

Langley says that after every festival, those behind the event always wonder if there will be a next time. It takes a lot of work to make the event happen each year. That fear was more prescient this time around. Though the organizers did announce a fall date for the 2020 festival, COVID-19 has now forced them to cancel the 31st Annual Lone Pine Film Festival. Those behind the festival seem determined to bring it back in 2021, but as with much during this pandemic, a big question mark looms.

There are other question marks, too. A prominent one has recently arisen around the name of the Alabama Hills themselves. In just the past few months, since the murder of George Floyd sparked protests across the United States, there has been renewed discomfort over the persistence of Confederate monuments and Dixie nomenclature. Some, including local public lands advocate group Friends of the Inyo, have called for the Alabama Hills to be renamed because the site was originally given its moniker by Lost Cause sympathizers. Most people don’t realize it was not named after the Southern state, but for the Confederate warship that sunk USS Hatteras, a Union gunboat, off the coast of Texas in 1863, at the height of the Civil War.

But during my visit, the biggest looming question mark, one I kept hearing expressed over and over among campers in the hills, regarded new legislation that passed in 2019 that turned the Alabama Hills into a National Scenic Area. Langley had a major role in that, too, as part of the Alabama Hills Stewardship Group. It took the group over 10 years to gain that designation. During the process, Langley says, they identified 40 user groups with competing interests in the hills. Many groups seem happy with the change in status, but there are some that worry about encroaching bureaucracy; they see a future where the rocks are bound by red tape.

So far, the only major change, at least according to Langley, is that there’s no mining allowed, but more than one group of campers I spoke to worry that this could be the beginning of the end of boondocking in the area.

Boondocking is a term for dry camping in an RV—no hookups, no site assignments, just pull up anywhere you like and camp. The Bureau of Land Management, which currently oversees much of the Alabama Hills, allows boondocking in many of the areas it controls throughout the state. On one of my first visits to the Alabama Hills, searching for movie rocks with my brother in 2018, we boondocked, pulling our RV into a canyon and camping between two giant rock walls. Unbeknownst to us, we had pulled right into the same canyon where Jamie Foxx and Christoph Waltz set up camp in Django Unchained. William Boyd and John Wayne had also shot murderers and fought off cattle rustlers at that same site. There was a certain magic to setting up camp exactly where filmmakers had set up cameras countless times over the last century.

Of course, there’s a negative side to the boondocking allowance as well. The more people camp in these sites, and the longer those campers stay, the harder it is for others to appreciate the scenery, whether for their cinematic history or their aesthetic grandeur.

Kevin Closson, who runs a blog called The Great Silence, which, among other things, helps readers find film locations in the Alabama Hills, recounts a recurring scenario: “Over the past few years I have gotten up before sunrise, made the few hours drive to Lone Pine, and then drove to the Alabama Hills. At this point, I get out, get my gear ready, and walk to what I want to take pictures and video of. Then the moment of truth arrives! I see an RV camper or similar vehicle planted right where I want to take pictures and video. ‘Oh well, there is always next time.’”

Even in light of such disappointments though, Closson wants “the maximum amount of freedom for people to visit the Alabama Hills and the Eastern Sierra,” admitting, “I am a little fearful that some people are going to force more regulation of the area and turn it into something it should not be.”

As a consequence of COVID-19, the Alabama Hills National Scenic Area, like much of the BLM-controlled land in California, was closed to visitors for most of the spring. It has since reopened, but as cases increase, there’s no telling if it will continue to allow visitors. It is difficult to predict what will happen to the festival, too, just as it is difficult to predict how the human use of the land will change under its new status. The one thing we can count on to not change—or to change at such a slow pace that it will be difficult to register in the course of a lifetime or even multiple lifetimes—are the rocks themselves. Curved like a giant bean, Gene Autry Rock will likely still be standing when COVID-19 is as ancient a malady as the Black Plague is to us today—what is less certain is whether there will still be fans who come to seek that stone because of the Western actor who lends it his name.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook