What Researchers Learned From the World’s Oldest Cookbook

Now, you can view—and cook from—these nearly 4,000-year-old ancient Babylonian recipe tablets.

The identity of the world’s earliest cookbook has long been a subject of debate—and depends a lot on what you consider a cookbook. Some scholars would say that De re coquinaria, an ancient Roman collection of recipes compiled around the 5th century takes the honor. But millennia before anyone whipped up a brain souffle, the ancient Babylonians were writing down recipes, some of which still work well today.

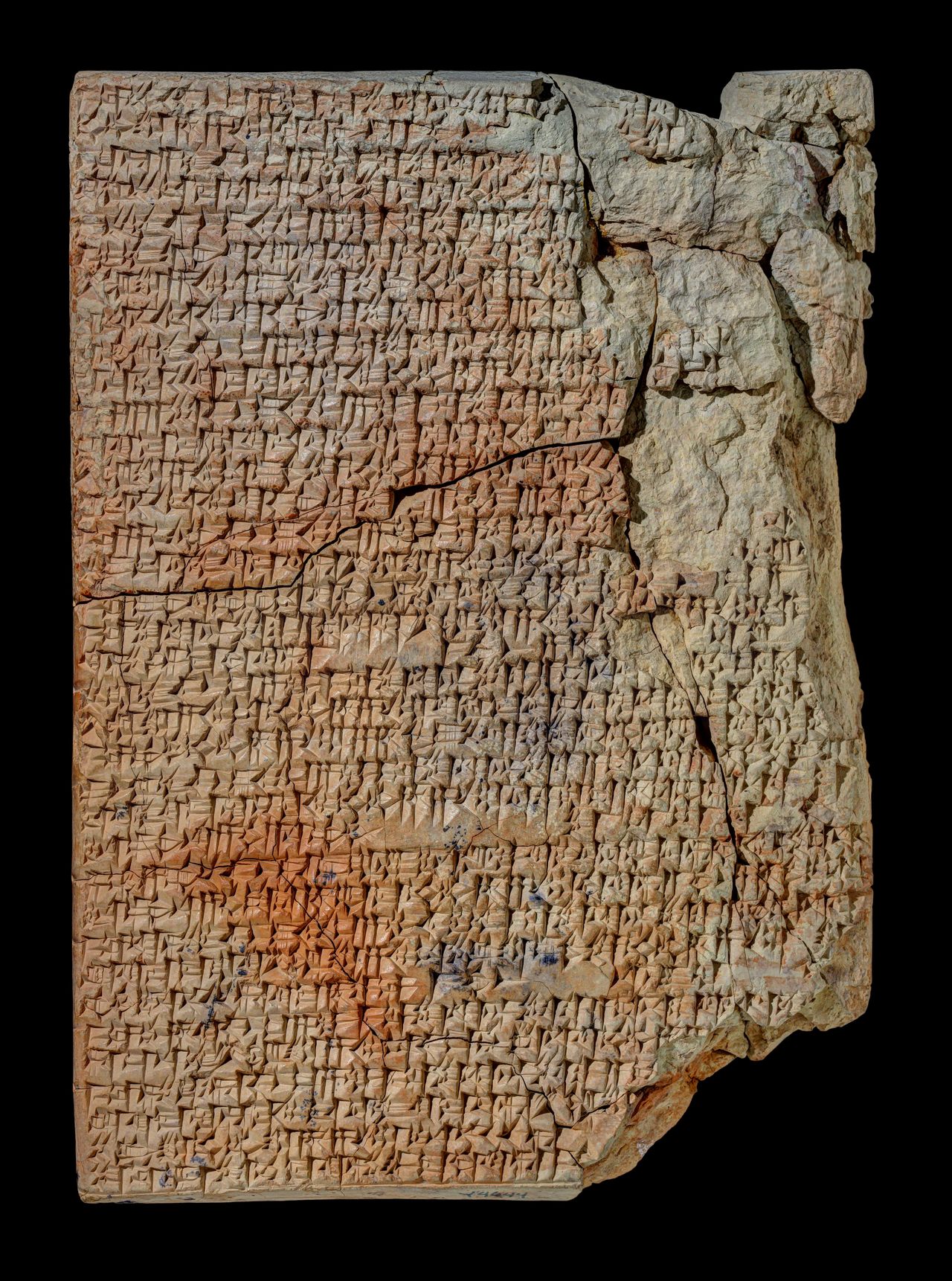

A set of four cuneiform clay tablets unearthed in what was once Mesopotamia contain the etched ingredient lists for dozens of aromatic stews, pies, and soups. Three of the tablets date back as far as 4,000 years. Researchers have been fascinated by these ancient “cookbooks” for years, but until recently, few people could actually see them. Since the 1930s, most of the 45,000 tablets, statues, and artifacts in the Yale Babylonian Collection had been stashed away in the bowels of Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library.

This year, for the first time, much of the collection, including these long-buried recipe tablets, is on display for the general public at the Yale Peabody Museum in New Haven. In March 2024, the museum reopened after a four-year, multimillion-dollar facelift. Part of the curatorial mission was to make these ancient treasures more accessible. To that end, the museum scrapped entrance fees and has gone to great lengths to bring these ancient texts to life.

“These great tablets, including one of the Epic of Gilgamesh, the world’s oldest cookbook, and many, many others were only ever seen by a very small number of people,” says David Skelly, director of the Peabody. More than 200,000 people have visited since the reopening. “So in a real sense, these objects are being seen by large numbers of people for the first time.”

Thanks to the efforts of researchers, curious archeology enthusiasts can also engage with the tablets in a host of ways. Mohamad Hafez, a New Haven-based artist and the chef-owner of Pistachio, a restaurant showcasing dishes from his Syrian homeland, created a 3D-printed sculptural work entitled Eternal Cities, which draws parallels between the glimpses of daily life contained in the tablets and the current culture of the region.

He found quite a few, especially when it came to cuisine. “To me, recipe books and tablets are a tool to share culture, to share food with so many people in divided times,” he says. Although these ancient Babylonian recipes certainly differ from the food he serves at his restaurant, he sees certain commonalities.

Thanks to Agnete Lassen, the associate curator of the Yale Babylonian Collection, Hafez has some idea of what people in his home region ate millennia ago. Lassen and her colleagues have attempted recreating a handful of the recipes—with mixed results. “I remember her saying some were really inedible,” Hafez says with a laugh. A milky broth with lamb, for instance, had an unappetizing beige color and gloopy consistency.

Part of the problem with reproducing these ancient recipes is that the tablets are mostly ingredient lists, typically sans further instructions. Presumably, the person writing them assumed that the reader would have sufficient culinary know-how to parse the shorthand. For a modern-day scientist, filling in the blanks requires some serious guesswork.

A vegetarian stew—inexplicably titled on a tablet as “Unwinding”—and a braised lamb stew with beets both turned out surprisingly well. The latter recipe incorporates both sour beer and tallow, both of which were commonly used ingredients at the time. “There’s blanks to fill in about how you would prepare and cook these things,” Skelly says. “But the mutton stew stood out as one that seemed more interpretable or familiar.”

As important as epic poems are, in many ways, it’s historical recipes and other mundane fragments of daily life that often captivate researchers’ imaginations. While most ancient cultures would have passed down something like a recipe orally, the ancient Babylonians were a highly literate society that etched even their everyday notes onto clay tablets.

“If you take all of the hieroglyphics we know about from ancient Egypt, you could fill up a bookshop. With Mesopotamian culture, you could fill up a massive library,” Skelly says. “It’s the equivalent of the phone calls and the emails of their day—thousands of documents that were written to literally be thrown away. It’s helping us to reconstruct an entire culture down to the minutiae.”

All those documents show details about what people were eating or how wealthy they might have been. One even contains the complaints of an aggravated teenager. “This is the first moment in human history where someone’s voice can go into our head,” Skelly says. “Across these thousands of years, you’re actually hearing what people thought, what they believed, what they wanted to share. And that’s an intimacy that we don’t get before we can read the words of these folks.”

As Skelly points out, learning what people ate also helps paint a picture of trade and economic relations. The emphasis on grain-based dishes and beers highlights Mesopotamia’s role as the breadbasket of the ancient world, as well as one of the earliest places where humans transitioned to an agricultural society. And the diversity of ingredients mentioned speaks to how sophisticated the trade routes of this interconnected society must have been.

“There’s so much we can glean about how people connected with one another,” he says. “Even though these people are talking to us from 4,000 years ago, there’s a continuity of civilization in this region that’s connected to living culture and the communities that are there today.”

Much archeology centers on connecting the dots. By studying the architectural footprints of houses, leftover organic residues, and these bare-bones recipes, researchers can paint a picture of what life might have looked like—and how people once ate.

Babylonian Lamb Stew

Adapted from the Yale Peabody Museum

- Prep time: 30 minutes

- Cook time: 90 minutes

- Total time: 120 minutes

- 4 servings

Ingredients

- 1/2 cup of chopped leek

- 2 cloves of garlic

- 1 pound of diced leg of mutton or lamb

- 1/2 teaspoon salt, or to taste

- 1 small onion, diced

- 1 teaspoon of ground cumin

- 1 cup of Persian shallots or spring onions, finely chopped

- 1 pound of fresh red beets, peeled and diced

- 1 cup of chopped arugula

- 1/2 cup of chopped fresh cilantro

- 1 cup of beer

- 1/2 cup of water

- 2 teaspoons of dry coriander seed

- 1/2 cup of finely chopped cilantro

- 1/2 cup of finely chopped kurrat (Egyptian leek), ramps, or wild leek

Instructions

-

Crush chopped leek and garlic together in a mortar to form a coarse paste. Set aside.

-

Heat the fat in a Dutch oven wide enough for the diced lamb to sit in one layer. Season the lamb all over with salt and sear on high heat until all moisture evaporates.

-

Add in the onion and sauté until translucent, but not yet brown. Add the Persian shallots and cumin.

-

Fold in red beet, arugula, and cilantro. Continue sautéing over medium-high heat until the greens are wilted and the mixture emits a pleasant aroma.

-

Pour in the beer and the water. Give the pot a light stir and bring to a boil.

-

Reduce heat and add in the crushed leek and garlic.

-

Let the stew simmer for about an hour, or until the sauce thickens and the lamb is tender.

-

While the stew simmers, pound the coriander seeds, kurrat, and cilantro together into a mortar to make a flavorful paste.

- Ladle the stew into plates and sprinkle it with the kurrat paste. The dish can be served with steamed bulgur or flatbread.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook