Eat Like You’re in the USSR With ‘The Soviet Diet Cookbook’

By making pizza approved by the Communist Party.

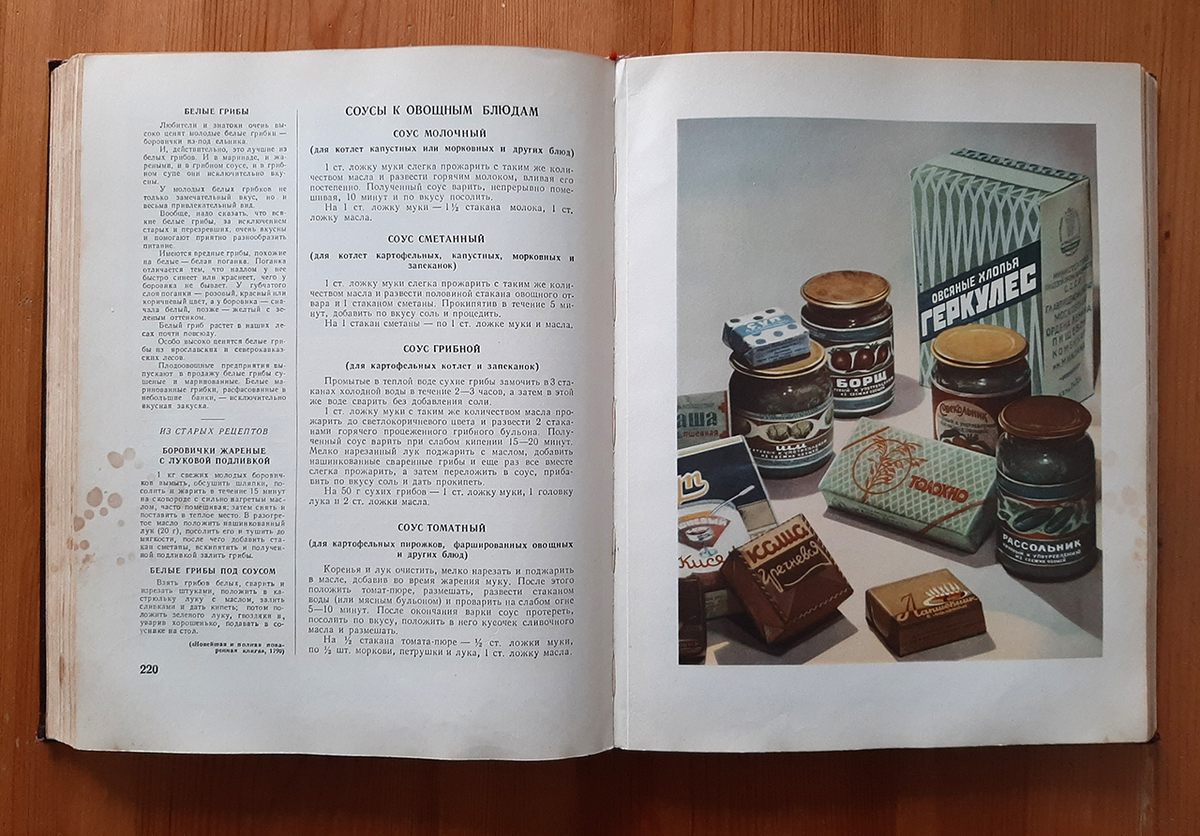

The 1939 cookbook of Soviet cuisine, The Book About Delicious and Healthy Food, opens with a Stalinesque slogan: “Towards abundance!” Earlier that decade, famines had devastated the Soviet countryside, and the memory of food shortages was not far off. But these realities appeared nowhere in the Communist Party-issued cookbook. Instead, it served up a utopian future.

The Book was intended to both feed and propagandize. After the 1917 revolution, which ended the Russian Empire and established the Soviet Union, the most well-known cookbook around was still decidedly un-Bolshevik: The Imperial Russian manual by Elena Molokhovets, A Gift to Young Housewives (1861), was replete with elaborate European dishes and household advice on aristocratic concerns such as servants and salons. But Soviet industrialization and ideology couldn’t stomach this bourgeois classic. In the 1930s, the Soviet Party developed a “rational” cuisine promoting what scholar Jukka Gronow calls “plebeian luxury.” Prepared by culinary experts from the Institute of Nutrition of the Academy of Medical Sciences, and published by the USSR Ministry of Food in 1939, The Book delivered a pragmatic and proletarian alternative. Several editions followed, and the expanded, glossy 1952 edition turned the cookbook into a bestseller. Since then, millions of copies have been sold.

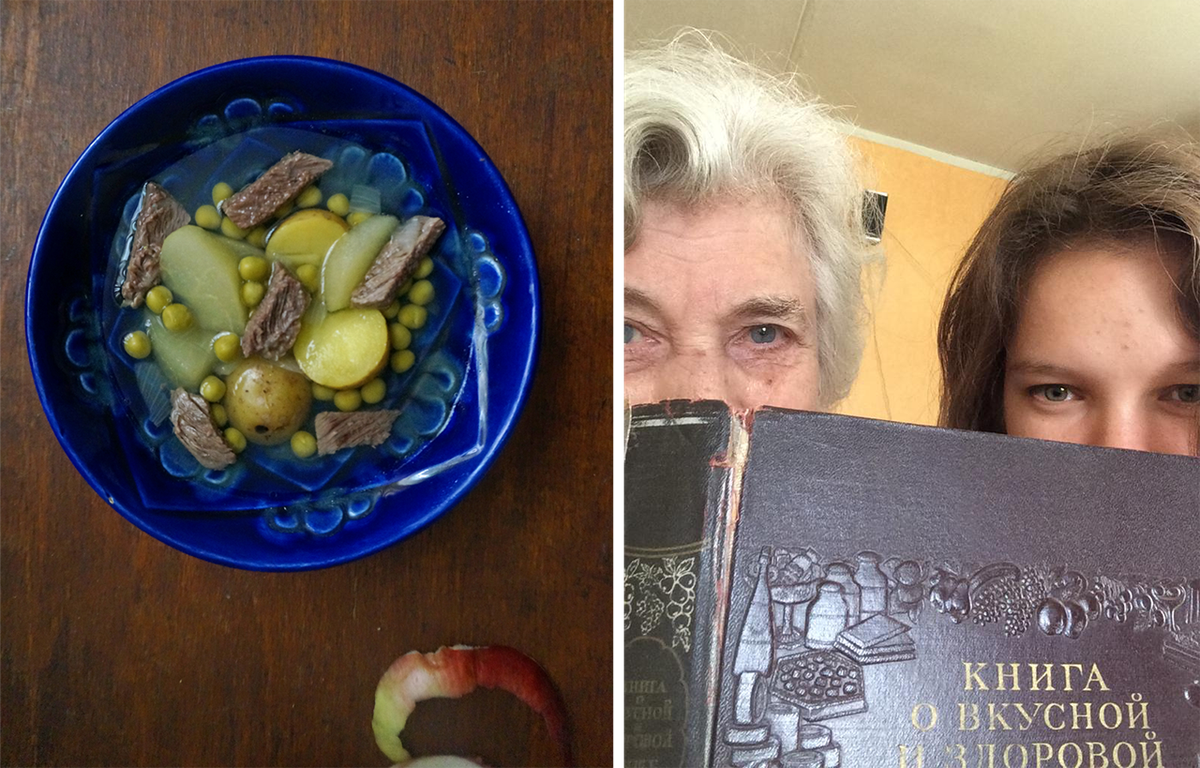

Nearly 80 years after The Book’s first release, millennial Muscovite Anna Kharzeeva (along with her grandmother Elena*) put The Book’s culinary vision to the test. Kharzeeva’s new cookbook, The Soviet Diet Cookbook, chronicles her skeptical but warm-hearted journey through the 400-page Socialist Realist behemoth. From 2014 to 2019, she tried 80 of its recipes, from a flurry of porridges to the pickle-brine soup solyanka.

Working through The Book, Kharzeeva points out internal inconsistencies. Despite a stated rejection of external, religious, or bourgeois influence, its recipes include versions of the Russian take on Easter hot cross buns (kulichi), the French-inspired Sharlotka apple cake, and a “historical recipes” section featuring foreign favorites with neutralized Russian names. While the ingredient lists in The Book assume plentiful products, Kharzeeva writes that many were available only as special-occasion rations (like caviar) or were rarely accessible (like melons). She also describes a category of rare ingredients used in the book, which include pineapples and real crab meat, as a “Soviet dream.” The cookbook contains no prep times, but Kharzeeva demonstrates that many recipes, such as the five-layer pastry puff kulebyaka, fell far short of liberating Soviet women from kitchen labor.

Grandmother Elena’s comments, meanwhile, reveal how Russians handled the contradictions of the Soviet Union and its promises of abundant, modern food. She shares that post-Revolution kids called a lie a “banana,” because finding a banana in the Soviet Union seemed as improbable as the lies told by Soviet politicians. Decades later, Kharzeeva’s mom still converts the price of clothing into bananas because they were so rare and expensive. Food could also serve as code: One would pass on a samizdat (an illegally published book) by saying “I ate the buckwheat and am now ready to give it to you.” Being “closer to the sausage (kolbasa),” on the other hand, meant you were a Party higher-up. Elena’s adaptations of recipes, meanwhile, illustrate the creative methods of Soviet subjects cooking in communal kitchens (a situation the Book never accounts for). For example, the circular chudo (literally, “wonder”) pot could be used to bake cakes or yeast rolls on top of a kerosene burner (before gas ovens were installed) or on a crowded, shared stove. Ingredients could be cleverly served, like caviar atop cooked egg halves instead of bread slices (to reduce the amount consumed), or repurposed, like orange peels hung on laundry lines to refresh clothes.

While the Soviet Diet Cookbook exposes the myths of the USSR, Kharzeeva also observes the politics of food in modern Russia. Despite Putin’s claims of Russian self-sufficiency, Kharzeeva, like Elena before her, faces high prices and scarcity. When making her recipes, a decently priced bell pepper or a piece of good lamb is nowhere to be found in Moscow. Contemporary regional tensions in the Eastern bloc, meanwhile, crawl into the presentation of “national” foods. While reviewing the Book’s borscht, Kharzeeva remembers seeing a menu flyer with both Ukrainian and Russian flags. A Ukrainian restaurant, trying to attract customers in the wake of Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea (when popular sentiment trended anti-Ukrainian), designed this awkward, seemingly chummy graphic of the former allies.

One of the most interesting and widely relatable dishes in The Book is “Toast with Vegetables” or what Elena calls “Soviet Pizza,” a concoction of dough, sour cream, and stewed vegetables that Kharzeeva judges “odd, but healthy and edible.” Pizza as a dish would have been hard to recreate in the Soviet Union. “Real” pizza became available as a fast food only in the 1970s, and it was fancy and expensive, consumed by many first-time patrons with a fork and knife. Forget Parmesan: Elena remembers that only three types of cheese, all locally made, were available to her in stores. Melted, processed cheese was such a rarity outside of the city that Elena’s friend in the village once mistook the silky stuff for face cream.

At the end of the day, as Elena says, “the shop is empty, but the fridge is full.” The Soviet Diet Cookbook tells the story of propagandist failures, poorly stocked shelves, and warm, resourceful homemakers, then and now. By Kharzeeva’s own admission, some recipes (deep-fried donuts or cornflake cookies) were a flop. But the Book could also delight with its far-away pictures and tasty, tried-and-true staples. The Book, as Kharzeeva writes, was “a whole world in itself, with its own idiosyncrasies, fairy tales, and flowers,” and The Soviet Diet Cookbook brings those Party illusions, and their inevitable folk adaptations, to the kitchen table.

“Soviet Pizza” Recipe from The Book About Delicious and Healthy Food

60 grams bread

75 grams milk

¼ egg

5 grams sugar

15 grams butter

30 grams sour cream

75 grams chopped cabbage

50 grams carrots

50 grams zucchini

50 grams apple

5 grams lettuce

5 grams dill

Cut bread into two pieces. Soak in 50 grams of milk mixed with egg and sugar. Bake slightly. Separately, simmer cabbage, sliced zucchini, and carrots in 25 grams milk and 10 grams butter. When cooked, lay cabbage, zucchini, and carrot slices on top of the bread. Lay apple slices, lettuce, and dill on that. Drizzle with butter and bake. Serve with sour cream.

Kharzeeva’s Adaptation of Soviet Pizza

Bread Base:

1 baguette

Or, if making the base Soviet style:

2-3 cups dried up baguette

½ cup milk

1 egg

Vegetable Topping:

½ teaspoon salt

Cumin to taste

2 medium or small eggplants

2 bell peppers

150 grams cherry tomatoes

3-4 walnuts

½ teaspoon dry ajika

If making a Soviet-style base, soak the bread in a mixture of egg and milk, then combine in a blender and form circles, about 4 inches in diameter. Bake on oiled foil for about 15 minutes on 350F.

Roast the vegetables. Line tray with foil, make cuts in eggplants and peppers. Bake tomatoes for about 15 minutes, until skin comes off easily. Bake peppers for about 45 minutes, and eggplants for 60-70 minutes.

Cool the vegetables and take skins off. Cut them up coarsely, mix together, and place on top of the baguette or bread base. Sprinkle with crushed walnuts and ajika (if you don’t have ajika, a mix of coriander, chili, and dried garlic will do). Serve warm or cold.

You can join the conversation about this and other stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

*Correction: This article previously confused Anna Kharzeeva’s babushkas. Her grandmother Elena was her primary adviser on Soviet recipes, not her grandmother Svetlana.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook